A Kingdom Built on the Economics of Merit. When we imagine medieval

A Kingdom Built on the Economics of Merit. When we imagine medieval

Sri Lanka, we picture kings, armies, stupas, and irrigation tanks. But behind these vast structures lay something less visible and far more powerful: a monastic economy that touched every field, every village, and every royal treasury.

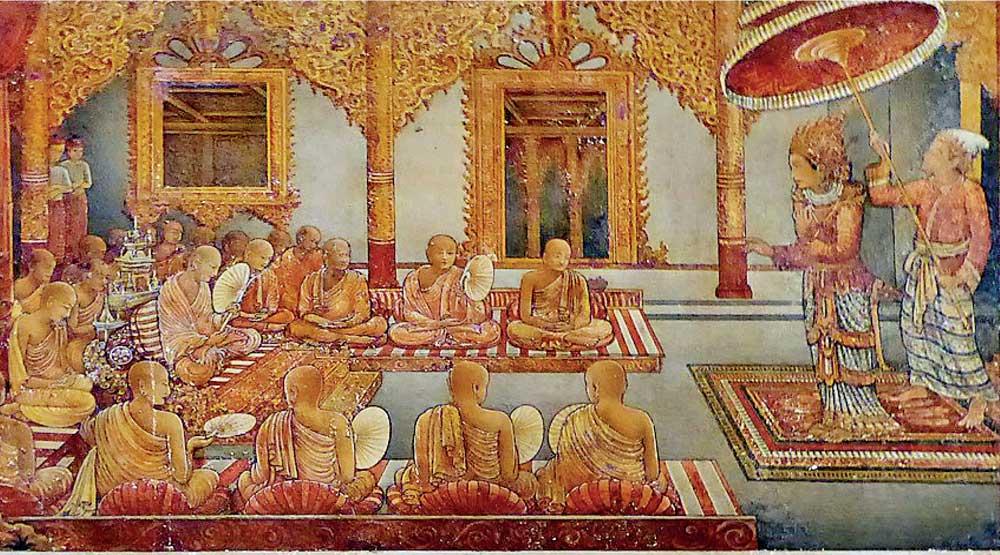

From Anuradhapura to Polonnaruwa and beyond, the Buddhist Sangha evolved into the island’s largest landowner, tax collector, employer, and creditor. To understand medieval Sri Lanka, we must understand not only its kings but its monks, for in many centuries the monastery was the bank, the granary, and the archive of the realm. This is not a story of corruption. It is a story of institutional evolution. As kings granted land to monasteries to earn merit, they inadvertently created a parallel economic order: a religious economy with its own administrators, accountants, and judicial authority, one that rivalled and occasionally eclipsed the power of the court. The Sangha became both moral authority and material institution, shaped by fields, canals, tenants, and grain. The real empire of medieval

Sri Lanka was not only of kings, but

of monks.

The Land of the Robe: How Monasteries Became Landlords

The earliest inscriptions from Anuradhapura show how rapidly monasteries accumulated land. Brahmi cave inscriptions from the 3rd–1st centuries BCE record paddy fields, garden plots, and whole villages donated to monks, often in perpetuity. In return, donors sought not political favour but spiritual merit. The economy of giving created the economy of the Sangha. By the 5th century, monasteries such as Mahāvihāra, Abhayagiri, and Jetavana controlled vast agricultural complexes. The Mahāvamsa depicts kings as generous patrons, but archaeology tells a sharper story: monasteries were among the most important land corporations in the island. They managed tenants, collected grain rents, hired labourers, oversaw harvest cycles, and petitioned kings when boundaries were violated. As Gunawardana famously argued in Robe and Plough, the Sangha had become an agrarian class in its own right. The robe was not merely a garment. It was an economic category.

Taxation Without a Treasury

When a village or field was donated, the state often remitted taxes for that land. This did two things:

- It deprived the royal treasury of income.

- It transferred fiscal authority to the monastery.

Thus, monks did not only receive land. They received the right to collect what the state once collected. Inscriptions use terms such as pangu, bōja, and vetti, referring to shares, grain rents, and labour obligations. These were not devotional offerings. They were structured dues. In effect, monasteries functioned like tax farms, except their legitimacy came not from bureaucratic appointment but from spiritual authority. A king could revoke a grant, but the karmic cost was high and the political backlash severe.

By Polonnaruwa, monastic estates formed a web of semi-autonomous fiscal zones embedded within the larger polity. Royal decrees regulated but rarely intruded upon monastic taxation, for to challenge the Sangha was to threaten the ideological core of kingship itself.

The Sangha’s Workforce: Tenants, Slaves, and Specialists

Medieval Sri Lankan monasteries were employers on a massive scale. The donor inscriptions that identify merchants, weavers, potters, and metalworkers reveal not only social identity but economic reliance. Large establishments such as Mihintale maintained:

- Artisan guilds (for carpentry, sculpture, and bronze-casting)

- Tenant cultivators who farmed monastic land

- Hereditary labour groups who performed ritual or agricultural duties

- Accountants who maintained registers on palm leaf

- Overseers who supervised irrigation and seasonal work

In this system, merit and labour intertwined. The lay world sustained the ordained world, and the ordained world legitimised the lay one. What emerges is not a passive ascetic institution but a complex economic engine. Even slaves appear in some inscriptions, usually as part of land transactions. They were allocated along with fields and water rights, bound into the economic structure of the monastery.

The Monks Who Built Tanks and Paid Debts

One of the most enduring myths is that the great irrigation works were solely royal creations. Yet many tanks, channels, and sluices were built or maintained by monasteries, often recorded in boundary stones or donative inscriptions. The monastic economy relied on water as much as the royal one. Maintenance of a reservoir was expensive: dredging, embankment repair, and labour hiring required stable revenue streams. Monasteries with large tenants could mobilise human resources more effectively than the palace. In many regions, the Sangha functioned as the hydraulic authority, ensuring that canals flowed, harvests remained stable, and famines were mitigated. There are inscriptions noting that monasteries repaid debts incurred by lay patrons. This practice gave monks the status of creditors, which reinforced the perception that the Sangha was a source of financial security. Loans were often tied to land: a debtor pledged a share of harvests until repayment. Thus, the monasteries moved gradually into the domain of banking.

Monks, Money, and Merit: Ritual as Currency

Every donation, a field, a gold coin, a slave, was part of an economic system governed by the logic of karma. Merit was not bought, exactly, but it was transacted. The donor gave something of material value. The monks performed rituals conferring intangible, spiritual value. The exchange produced both religious fulfilment and institutional accumulation. This gave rise to what anthropologists call moralised economy: a system where economic behaviour was justified through ethical and cosmological principles. Merit-making was both a religious practice and an economic engine that funded hospitals, refectories, shrines, roads, and irrigation channels.

By the 10th century, large monasteries had their own treasuries. Royal ledgers frequently recorded gifts to the Sangha in gold coins (kahāpana), silver, pearls, and textiles. Temples also minted their own ritual objects: lamps, reliquaries, and votive tablets. The Sangha thus controlled both the flow of agricultural wealth and the circulation of precious metals.

The Monastic Record Office

Beyond wealth, monasteries-controlled information. Many inscriptions explicitly assign monks the role of record-keepers in boundary disputes, land reallocations, and irrigation management. Since monks were literate and trained in scriptural memorisation, they were uniquely positioned to archive and validate documents.

The result was a profound institutional shift:

- Kings ruled by decree.

- Monasteries ruled by record.

A royal grant engraved in stone became the legal property of the monastery. A monastic scribe, not a royal clerk, often served as witness. The inscription itself, carved on a stone slab, a cave wall, or a boundary marker, held judicial authority in local disputes. This combination of economic power and archival control made the monasteries indispensable to the functioning of the state.

The Polonnaruwa Tension: Monks vs. Kings

Polonnaruwa sharpened the tension between royal ambition and monastic autonomy. Parākramabāhu I undertook sweeping reforms to unify the Sangha, partly to secure ideological stability, but partly to bring monastic wealth under more direct royal oversight. He succeeded in ritual terms but only partially in economic ones. Monasteries retained their estates, their tenants, their treasuries, and their autonomy. Kings could not afford to alienate them. When Polonnaruwa collapsed under Magha’s invasion, monasteries again proved decisive. Their networks protected relics, sheltered refugees, and preserved continuity. They remained the island’s financial stabilisers even as armies burned fields and plundered cities. By the time the kingdom relocated to Dambadeniya, monastic estates had become the backbone of regional resilience.

What Happens When Monasteries Hold Capital?

The medieval Sri Lankan experience reveals a unique dynamic: The Sangha became the largest collective landowner because its capital was ideologically protected and perpetually expanding. This differs from feudal Europe, where monastic wealth could be seized by kings, or from Southeast Asia, where temple networks often dissolved with dynastic change.

In Sri Lanka, the donation of land to the Sangha was not merely economic generosity. It was a ritual necessity that kept kingship legitimate and karmically potent. Thus, every king strengthened the institution that could later outlast him.

This structural paradox, a decentralised religious economy supporting a centralised monarchy, shaped the island’s history for over a millennium.

Echoes Today

The legacy of the monastic economy persists. Many of Sri Lanka’s oldest temples remain custodians of village lands. Benefaction still shapes rural relationships. Ritual giving remains central to public life. These are not remnants of a vanished medieval world but living continuities of a system where economic and spiritual obligations intertwined. Modern observers sometimes mistake this for anachronism. In reality, it is the endurance of a worldview in which material generosity and moral cultivation form a single ethic.

Conclusion: The Treasury Behind the Stupa

Kings ruled medieval Sri Lanka with swords and decrees, but monks ruled it with fields, grain, and record-keeping. The Sangha was not only a spiritual institution. It was an agrarian corporation, a financial stabiliser, and a judicial authority. Its stability ensured the island’s stability; its archives preserved the island’s memory; its wealth underwrote the splendour of stupas and shrines that still stand today. The stone stupas of Sri Lanka testify to devotion.

The monastic ledgers that once lay behind them testify to something else: a kingdom whose greatest treasury was not in the palace but in the monastery.