In recent decades, society’s fascination with murderers, serial killers, and other criminals has gone beyond horror and shock. They have become characters in pop culture, often glamorized, romanticized, fetishized, or made into objects of fascination. Ted Bundy, Richard Ramirez (“The Night Stalker”), Jeffrey Dahmer, all are infamous not only for their crimes but also for having a large number of admirers, fans, and even romantic relationships created in absentia. But why does this happen? What drives this glorification, and what dangers does it pose?

Where Does the Fascination Stem From?

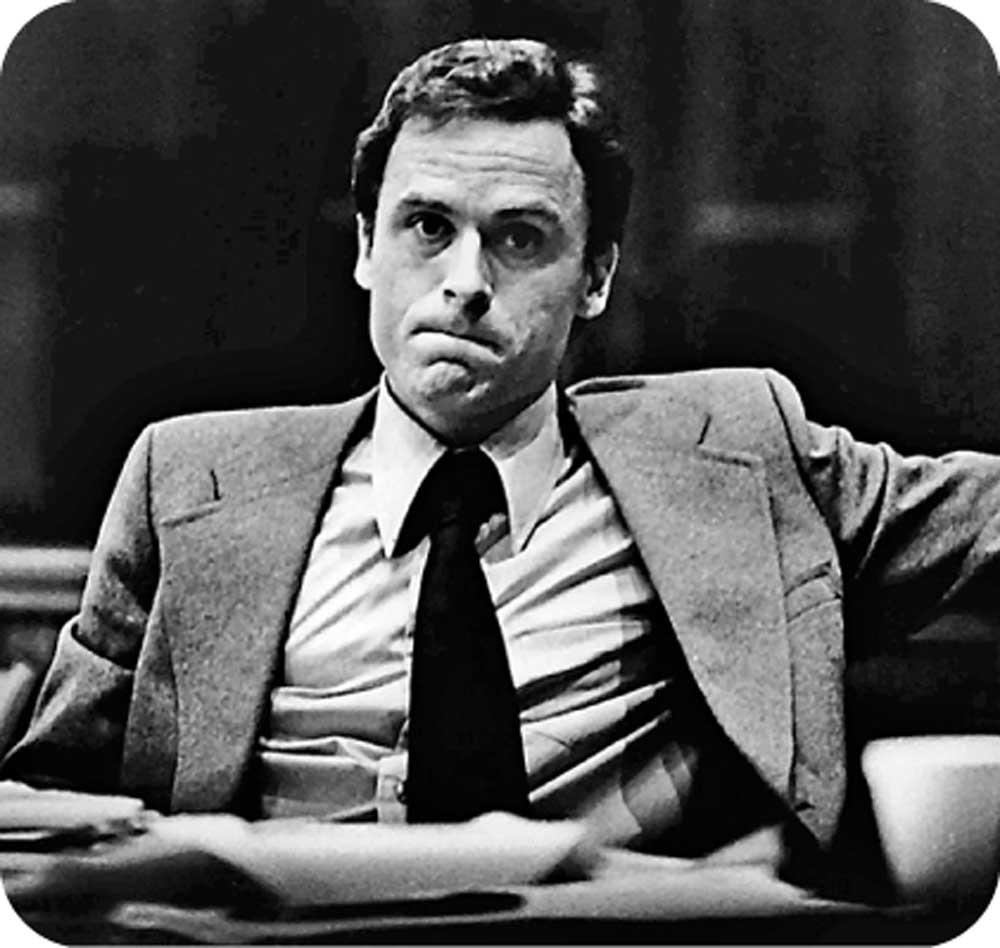

The romanticization of murderers often begins with how they are portrayed. Serial killers like Ted Bundy are remembered not only for their horrific crimes but for their supposed good looks, intelligence, and charm. Bundy was a law student, articulate, confident, and seemingly ordinary, and for some reason, that contradiction between appearance and reality fuels a dark allure. The idea that someone so “normal” could harbour such evil fascinates the human mind. When films like Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile cast Zac Efron as Bundy, the line between critique and glorification grows dangerously thin. Audiences are captivated not by the horror, but by the seduction of danger, the “bad boy” taken to lethal extremes. Psychologists term this attraction hybristophilia, the  sexual or romantic fascination with individuals who commit violent crimes. It’s not new, but it’s more visible than ever. During Bundy’s trial, women filled courtroom benches, some professing love or admiration for him. Richard Ramirez, “The Night Stalker,” who murdered and assaulted numerous victims, received fan mail and even married a woman, Doreen Lioy, while in prison. The psychological reasoning behind this phenomenon stems from the fantasy of being the one who can “fix” or “understand” the dangerous man. Some are drawn to the forbidden fruit; to the thrill of danger itself. There’s a perverse sense of power in being emotionally connected to someone who terrifies everyone else.

sexual or romantic fascination with individuals who commit violent crimes. It’s not new, but it’s more visible than ever. During Bundy’s trial, women filled courtroom benches, some professing love or admiration for him. Richard Ramirez, “The Night Stalker,” who murdered and assaulted numerous victims, received fan mail and even married a woman, Doreen Lioy, while in prison. The psychological reasoning behind this phenomenon stems from the fantasy of being the one who can “fix” or “understand” the dangerous man. Some are drawn to the forbidden fruit; to the thrill of danger itself. There’s a perverse sense of power in being emotionally connected to someone who terrifies everyone else.

The Role of Media and Pop Culture

This romanticization doesn’t emerge in isolation. The media plays a decisive role in shaping how society perceives criminals. True crime documentaries, biopics, and novels often dramatize the lives of killers in a way that humanizes, or even glamorizes, their actions. Cinematic lighting, emotional backstories, and sympathetic portrayals transform them into complex antiheroes. In such portrayals, victims become secondary, often nameless and faceless, while the killer’s psychology takes centre stage.

The audience is invited to empathize with the perpetrator, to understand him, to see him as a tragic figure shaped by circumstance rather than pure malice. The result is moral distortion. When viewers begin to identify with the criminal, the boundary between empathy and endorsement becomes blurred. Instead of condemning, we start to understand, and that understanding sometimes gives birth to admiration. There’s also an undeniable voyeuristic pleasure in watching or reading about crimes. People are fascinated by what terrifies them. Crime stories let audiences peer into the abyss without falling in. That adrenaline rush, the morbid curiosity, can easily be mistaken for attraction. In the age of social media, the fascination mutates. Edits, fan pages, and romanticized artwork of serial killers circulate widely online, turning real-life murderers into cult figures. The internet provides fertile ground for unhealthy parasocial relationships, one-sided emotional attachments to criminals who should instead evoke repulsion.

The Danger of Glamorizing Violence

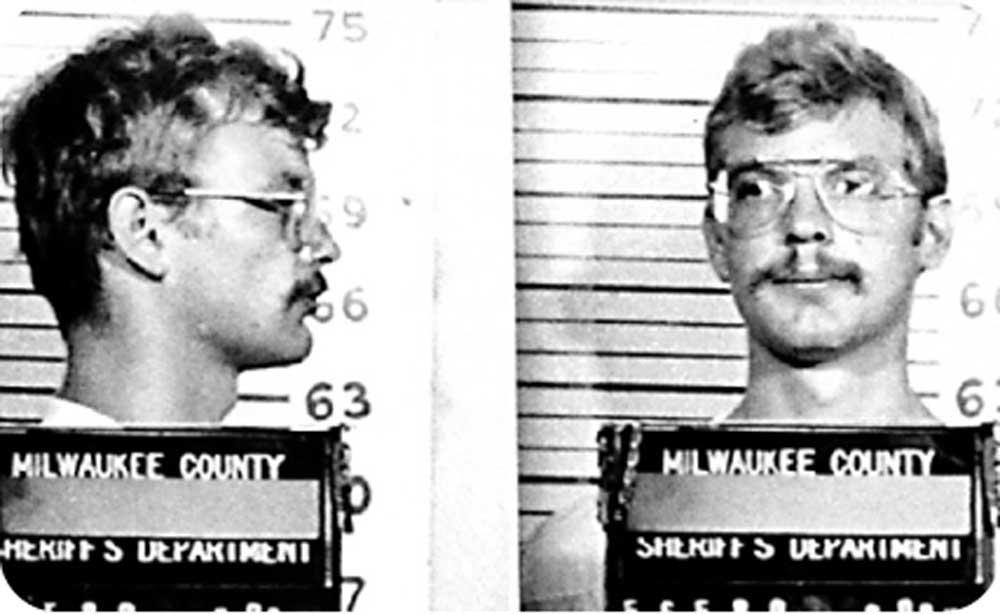

The consequences of glamorization are profound. Romanticizing criminals minimizes the pain of victims and distorts our collective sense of morality. It feeds into a dangerous narrative where violence becomes intertwined with desire, and manipulation is mistaken for charm. For young or impressionable audiences, this normalization of toxic behaviour can have lasting impacts, making cruelty look like charisma and control masquerade as passion. By aestheticizing evil, society desensitizes itself to real suffering. Instead of viewing killers as cautionary examples of depravity, we begin to see them as tragic or misunderstood. This softening of perception erodes empathy for victims and contributes to a culture where emotional detachment is trendy. When Netflix viewers gush about Bundy’s “handsomeness” or when social media edits of Jeffrey Dahmer go viral with romantic music, the moral compass falters. The audience forgets that these men destroyed lives, they were murderers, not misunderstood poets.

The consequences of glamorization are profound. Romanticizing criminals minimizes the pain of victims and distorts our collective sense of morality. It feeds into a dangerous narrative where violence becomes intertwined with desire, and manipulation is mistaken for charm. For young or impressionable audiences, this normalization of toxic behaviour can have lasting impacts, making cruelty look like charisma and control masquerade as passion. By aestheticizing evil, society desensitizes itself to real suffering. Instead of viewing killers as cautionary examples of depravity, we begin to see them as tragic or misunderstood. This softening of perception erodes empathy for victims and contributes to a culture where emotional detachment is trendy. When Netflix viewers gush about Bundy’s “handsomeness” or when social media edits of Jeffrey Dahmer go viral with romantic music, the moral compass falters. The audience forgets that these men destroyed lives, they were murderers, not misunderstood poets.

It Happens Right Here in Lanka Too!

This phenomenon is not confined to Western cultures. In Sri Lanka too, we’ve begun to see similar patterns of fascination, though they manifest differently. Take the case of Ishara Sewwandi, for instance, a young woman accused of posing as a lawyer and infiltrating the legal system. While her actions didn’t involve violence, the public reaction revealed the same underlying fascination with deception, intelligence, and rebellion. Social media erupted with memes, videos, and debates, many commenting on her looks and confidence rather than the seriousness of her crime. What should have been a sobering discussion on ethics and accountability became a spectacle. The narrative shifted from legal misconduct to intrigue, the mysterious woman who fooled the courts. In many ways, the public’s fascination mirrored the Western media’s romanticization of killers. The focus moved from wrongdoing to personality. It’s a troubling reminder that sensationalism knows no borders.

In Sri Lankan society, where respect for authority and moral order is deeply ingrained, such figures stand out as symbols of rebellion. The media amplifies this allure, framing their stories dramatically, almost theatrically. What results is warped admiration for audacity; a culture that sometimes praises rule breakers for being cunning rather than condemning them for their deceit.

The Responsibility of the Media and the Audience

The issue, then, is not only with criminals but with the stories we tell about them. Filmmakers, journalists, and writers have a responsibility to portray these figures truthfully, without romanticizing violence or deception. When true crime is treated as entertainment, it trivializes human suffering. Storytelling can educate and expose, but it can also distort and glorify. Audiences too share responsibility. We must learn to consume media critically, to question what emotions are being manipulated and why. Casting a handsome actor as a murderer, writing poetic dialogue for a fraudster, or adding suspenseful music to a courtroom scene, all these choices affect how we perceive morality. The public’s role is to look beyond the dramatization, to remember that beneath every “fascinating” criminal lies a trail of pain and loss.

What This Says About Us

Ultimately, the romanticization of killers and criminals reveals as much about us as it does about them. We are drawn to darkness because it reflects our hidden curiosities, our fascination with power, danger, and control. We crave the thrill of chaos while pretending to be safe from it. But admiration should never replace accountability, and fascination should never overshadow empathy. Whether it’s Ted Bundy in the US or Ishara Sewwandi in Sri Lanka, the danger remains the same: when we start to find beauty in evil, we risk losing sight of what goodness truly means. The next time a film, documentary, or headline tempts us to marvel at a murderer’s charm or a con artist’s boldness, we should pause and ask ourselves; who are we really admiring? The criminal, the storyteller, or the spectacle? Perhaps the real danger lies not only in the killer themselves but also in our willingness to make them seem beautiful.