In an age obsessed with speed, scale, and spectacle, mentorship remains one of society’s most undervalued quiet forces. It does not trend, it does not announce itself with metrics or slogans, and it rarely delivers instant results.Yet, for adolescents standing at the most volatile crossroads of human development, mentorship can mean the difference between becoming shaped by circumstance and being guided by conscience. The question is not whether teenagers need mentors, but whether adults are still willing to be them.

In an age obsessed with speed, scale, and spectacle, mentorship remains one of society’s most undervalued quiet forces. It does not trend, it does not announce itself with metrics or slogans, and it rarely delivers instant results.Yet, for adolescents standing at the most volatile crossroads of human development, mentorship can mean the difference between becoming shaped by circumstance and being guided by conscience. The question is not whether teenagers need mentors, but whether adults are still willing to be them.

Adolescence is not merely a passage of years; it is a neurological overhaul – a time when, as neuroscientist Dan Siegel has repeatedly explained, the teenage brain undergoes a dramatic pruning process. Neural connections that are used are strengthened; those neglected are trimmed away. This pruning is not random. Experience decides what survives. The adolescent brain is primed for risk, novelty, emotional intensity, and peer approval, while the regions responsible for long-term judgment and impulse control are still under construction. In other words, teenagers are not broken adults; they are unfinished ones. In such a fragile window, guidance is not interference; rather, it is scaffolding.

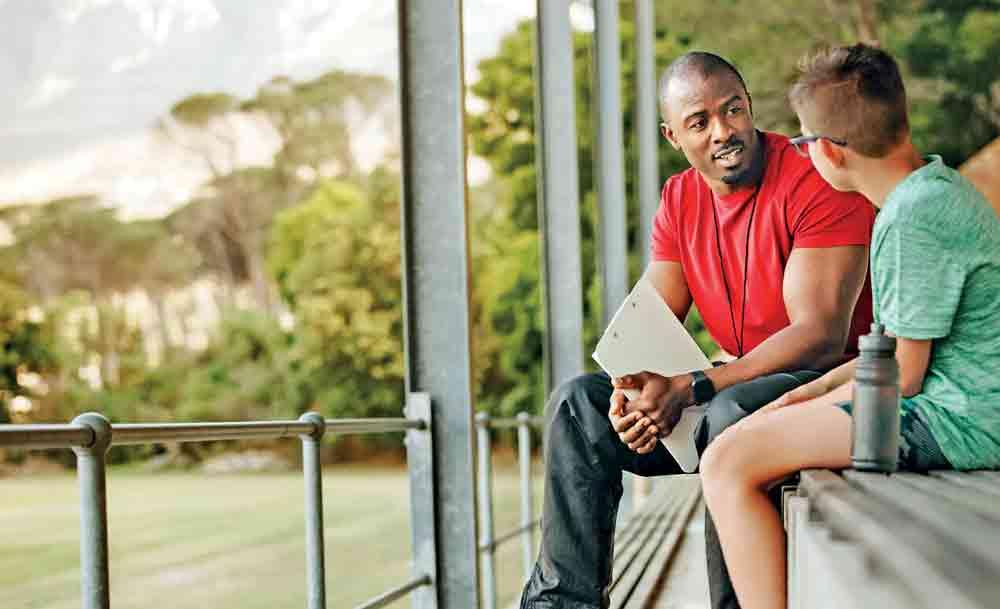

A mentor, unlike a parent or teacher bound by authority, occupies a rare middle ground.

The mentor sees without owning, advises without controlling, and corrects without humiliating. For a teenager navigating identity, morality, ambition, and belonging, this relationship offers something irreplaceable: perspective without pressure. A mentor becomes a living reference point, modelling how an adult handles failure, restraint, disagreement, and responsibility. In neurological terms, this modelling matters. The adolescent brain learns less from instruction and more from observation. What a mentor does carries more weight than what they say.

This idea is not new. Long before leadership seminars and coaching certifications, mentorship was woven into civilisations. The ancient guru-shishya parampara tradition of the Indian subcontinent placed students within the household of the guru. Learning extended far beyond scripture or skill. It included how one spoke to elders, managed anger, handled money, treated labour, and lived with discipline. Education was not a transaction but an immersion. Character was absorbed through proximity.

Modern life, of course, makes such arrangements impractical, even inappropriate in today’s society that is likely to be quick to judge and bandy words bordering on paedophilia. Yet the principle remains relevant: mentorship works best when it is consistent, relational, and rooted in real life rather than occasional advice. A practical modern mentorship is not a motivational talk once a year. It is showing up regularly, listening without rushing to fix, asking difficult questions, and allowing a young person to witness both the limits as well as the strengths of adulthood unfiltered.

In practice, this may look like a weekly conversation, shared work on a project, guided exposure to decision-making, or simply being present during moments of confusion and disappointment. It requires patience in a culture addicted to immediacy. It also requires humility. Mentors must accept that they are not shaping replicas of themselves but helping another human being discover their own contours.

Yet mentorship is not without cost, and this is where romantic notions often collapse. The challenges are real, particularly for the mentor. Time spent with a mentee is time taken from one’s own family, work, and rest. Resentment can quietly build at home when children or spouses perceive that emotional energy is being diverted to a “random” teenager. This tension is rarely acknowledged in glowing articles about social responsibility, but it is one of the main reasons mentorship quietly dies, as good intentions collide with domestic reality.

Balancing this requires transparency and boundaries. Mentorship must be structured, timebound, and understood by all involved. When families are excluded from the purpose and limits of mentorship, resentment is inevitable. When they are included, mentorship can become a shared value rather than a private burden. The mentor, too, must resist the saviour complex. Adolescents do not need rescuing; they need steady adults who do not disappear when things become inconvenient. There is also the uncomfortable truth that mentorship exposes our own inconsistencies. Teenagers are perceptive. They notice hypocrisy instantly. To mentor is to submit oneself to silent scrutiny. This is perhaps why mentorship feels so demanding in an era that prefers authority without accountability.

And yet, the cost of not mentoring is far greater. In a world where adolescents are increasingly raised by algorithms, peers, and performance pressure, the absence of grounded adult guidance leaves a vacuum quickly filled by noise. We lament emotional fragility, poor judgment, and moral confusion in the young while withdrawing from the very relationships that once mitigated these traits.

Mentorship is not a programme. It is a posture. And should we as adults refuse to adopt it, we become a generation that demands resilience without modelling it. We criticise entitlement in the young and condemn adolescent fragility, even as we retreat from the relationships that once steadied young lives. And in choosing distance over involvement, we teach indifference by example. In a society eager to speak about values but reluctant to embody them, the absence of mentorship is not an oversight. Rather, it is a quiet abdication of adulthood itself. In a society eager to outsource responsibility, mentorship remains one of the last deeply personal acts of faith in the next generation, and one that we are bound to undertake if we are to have a claim in shaping the values of the next generation.