When women like Tasneem speak, they speak for every survivor told to stay silent. Cut as a child and shunned for naming it, Tasneem has become one of the few voices from Sri Lanka’s Dawoodi Bohra community to confront the truth about female genital mutilation (FGM). In this conversation, she breaks open the silence around faith, control, and belonging; exposing the power, fear, and love that shape a practice too long defended in God’s name. This is not a sob story. It is testimony. It is also a map of the machinery that keeps women cut, and quiet.

When women like Tasneem speak, they speak for every survivor told to stay silent. Cut as a child and shunned for naming it, Tasneem has become one of the few voices from Sri Lanka’s Dawoodi Bohra community to confront the truth about female genital mutilation (FGM). In this conversation, she breaks open the silence around faith, control, and belonging; exposing the power, fear, and love that shape a practice too long defended in God’s name. This is not a sob story. It is testimony. It is also a map of the machinery that keeps women cut, and quiet.

THE PRICE OF SPEAKING

Q When did you decide to break your silence, and what happened when you did?

“The only reason I could speak was because both my parents are gone, and I have no brothers or sisters. My extended family, every one of them, stopped speaking to me. They haven’t said a word since I went public. So yes, there is a price for standing up. But the freeing thing is, the worst has already happened. It can’t get worse.”

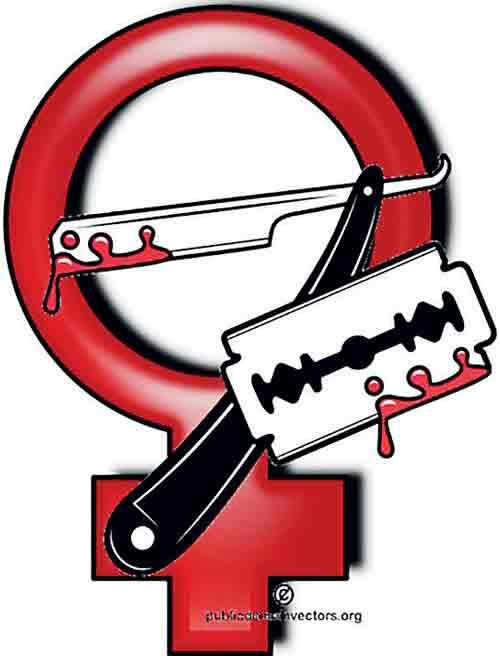

CALL IT WHAT IT IS MUTILATION, NOT “CUTTING”

Q You’re very firm about calling this practice FGM and not FGC or any other softened term. Why does that distinction matter so much to you?

“Because that’s what it is: mutilation. Not a nick, not a scratch, not a ‘cut.’ It’s harm.

Why are we calling it FGC and FGM as if one is less serious? Whether it’s a nick, a scratch, or the removal of tissue, it’s all mutilation. The WHO doesn’t differentiate; they call it FGM — Types 1, 2, 3, and 4.

We’ve signed the Human Rights Convention. We should use that language. What we’re doing in our communities is FGM Type 1 or Type 4. Let’s stick to that.Because language matters. The moment you call it ‘cutting,’ it sounds smaller, softer, more acceptable.

And it’s not. Call it what it is, mutilation, and you can’t hide from what’s being done.”

THE OATH OF FEALTY

Q You’ve spoken about how fear holds such a small community together. What exactly keeps people from questioning the system, and how does the religious oath, the misak, enforce that control?

“When a pope or pontiff Da'i al-Mutlaq dies and the next one takes over, every member must swear a misak, a vow of absolute loyalty. It’s couched in religious language, as if you’re promising to go to war for him. It’s ancient and completely hierarchical.

If you haven’t taken the misak for that particular leader, you can’t even enter our mosques. That’s how they define belonging. That’s why Sunnis seem freer: if you’re Muslim, you belong. For us, loyalty decides faith.

We’re about 2,500 to 2,600 people in Sri Lanka. Tiny, in a sea of twenty-odd million. The only way to keep such a small flock together is by being rigid. Recently, there’s been a charm offensive within the community to stop fractures, but that only goes so deep.

Ultimately, if you break away, you’re dead to them. They will not speak your name; they will not attend your wedding or your funeral. That warning keeps everyone obedient. Even those who secretly agree with me can’t show it.

Social media is watched; like everything else. If someone likes my post, it’s reported. Absolute silence.”

THE FUNERAL THAT EXPOSED HYPOCRISY

Q You once said your mother’s funeral was the moment you saw the hypocrisy most clearly.

“My mother was devout. When she died, I wanted her buried in the tradition she believed in. The Bohra Mosque made it a nightmare; fees, paperwork, pledges.

Two minutes from our house was a Sunni Mosque. Their secretary, a near neighbour knew us. He came and said, ‘If they’re difficult, we’ll do the whole thing for you.’ After Jummah the next day, they raised £5,000 for my mother’s funeral. When I explained that our mosque had agreed, they instead used the money collected to build three wells in my mother’s name. The difference to me was how the Sunni mosque wanted to make the process of laying my mother to rest as easy for us as possible. They understood that we were alone and grieving and they were trying to handle that with empathy and humanity

However, my own mosque only agreed after we had sworn new loyalty and performed all the necessary obligations. My husband and I complied because it was my mother. But that’s when I knew that I had come to a point where I could never go back to blind belief and loyalty.

I’m not saying that everyone in the mosque was mean or unsympathetic, but it was a moment for them to assert control when we were helpless, and that was a flexing of power.

HISTORY AND BELONGING

Q How does the Bohra story of exile and migration feed the need for belonging and obedience?

“Our story is a chain of outsiders. From Persia to Yemen to Cairo under the Fatimids, then to India under the Mogul Emperor, Akbar the Great. Always displaced, always the minority. So, the mosque becomes identity. It sells you belonging, and belonging becomes a leash.

If you’re the perpetual outsider, you’ll pay anything to stay inside something.”

THE CULTURAL ROOTS OF FGM

Q Where, historically, does this practice come from?

“It isn’t Islamic. It’s cultural. Ninety-five percent of women in Egypt have undergone it; Yemen’s numbers are almost as high. Our version came from those regions during our Fatimid Caliphate in Cairo.

It predates Islam. It’s African from Pharaonic Egypt, possibly as far back as the 5th century BCE. But they can’t say that because the whole religious justification collapses. So, they pick one obscure saying, call it Sunnah, and pretend it is divine law. It’s about control, not faith.”

THE HIDDEN HARMS BODY, MIND, AND FAITH

Q When people talk about FGM, they mostly focus on the physical act. From your experience, what does the real harm look like?

“Most conversations about FGM focus on the physical; the cutting, the scarring, the medical complications. Important, yes. But incomplete. It’s not just physical harm. It’s psychological. It’s emotional. It’s sexual. It’s spiritual.

It’s broken my trust in my religion; the very place I go to for spiritual comfort. I can’t look at my imams or priests and trust them to guide me because they don’t understand me as a human being.

If they’ve made this fundamental error, how can I trust them to understand anything else in the Quran or the Hadith?”

MEDICALISATION AND DENIAL

Q How would you explain that taking the practice over to doctors makes it worse?

“In some Asian countries it used to be just symbolic. Once doctors took over, it became precise, deliberate.

Mine was done by a GP. My parents drove me to the surgery. I remember arriving, and then being home again, nothing between. Years later a Pakistani gynaecologist in Manchester examined me and said, ‘I can’t see any damage; maybe you were born this way.’ I told her I wasn’t. She repeated it. That’s how deep the focus only of physical damage runs, even in medicine. As there was no scaring due to the precise medicalisation of the procedure, my personal lived testimony was dismissed.”

THE UNSPOKEN IMPACT ON MARRIAGE

Q How has this experience affected your relationship with your husband, and your sense of yourself as a woman?

“I’ve said so many times to him, I feel like I’ve failed you as a wife because we have never had a normal sexual relationship. We don’t even know what normal is.

Could it have been better? Could it have been richer? Who knows. It’s as good as it’s ever going to be. But is this as good as it would have ever been?

That’s what mutilation means: living forever with the ghost of what might have been. It’s like asking someone with a disability to imagine being able bodied. You can’t.”

MONEY, POLITICS, AND SILENCE

Q How do finances keep this machinery running?

“We pay zakat and silafitra; every hearth fire in your house means another payment. Weddings, deaths, the misak, everything goes through the mosque. If identity is defined by milestones celebrated or conducted via the mosque, then being torn away from that structure is worse than anything imaginable from the community’s point of view.”

CONSENT AT 18 – A RADICAL IDEA

Q You’ve suggested a radical new idea, allowing women to make their own decision about this practice at 18. Why?

“Because if communities insist this practice is religiously essential, then let women choose when they turn 18.

Let your girls grow up and make that choice. She must sign a form saying she’s had mandatory counselling, not just religious, but state-run medical counselling, so she understands exactly what’s happening to her body.

Even after counselling, when she’s on the medical table, she can tell the doctor, ‘I really don’t want to do this, but my family is insisting.’

She goes to the hospital, everyone thinks she’s had the procedure, she comes back, who’s going to check? You’re giving her the final option to say NO without anyone knowing.”

THERAPY AND HEALING

Q How did therapy transform you from grief to clarity?

“I went to therapy after my mother died, because you can’t talk about this while your mother is alive, that would be airing dirty linen. I finally found help through the NHS.

All my therapists were Afro-Caribbean. That distance helped. They were looking at me, not my community, not my culture, just me. Listening without any judgment whatsoever.

For a year, I cried. Ugly crying. Crying until I had headaches. Crying until I could barely see to get the bus home. I wrote letters to my dead mother. I shouted. I raged. I got, in my words, all the yuck out.

That’s why now, when I talk about it, I can be so calm. I’ve cried it all out.”

LOVE OVER RAGE

Q You often say love must lead this fight. Why love, after everything?

“Because anger is easy.

We’re the smaller party, always accused of betraying our people. Rage only proves them right. Love is harder. After the Easter bombings, Muslims were demonised; I refuse to add to that.

We must say: I love you enough to tell you the truth. Change happens when people feel loved, not attacked.”

THREE THINGS TASNEEM WANTS PEOPLE TO HEAR

- This isn’t an attack.

We’re not hurting our religion; we’re begging it to heal. I truly don’t hate the people who did this to me or the community of my birth that thought this was mandatory.

- It comes from understanding, not hate.We know you think you’re doing good, ask who’s good it is.

- If it must be done, let it be with consent.Not to a child. Education first, counselling first, and always the right to say no.

FAMILY, LOSS, AND HOPE

Q After such loss, what still draws you home?

“My husband’s English family accepted me completely. Friends in Poland and Malaysia are like siblings.

But it’s not the same. From 2014 to 2019 I didn’t come back to Sri Lanka. What would I come for if family isn’t there?

I keep hoping that once the older uncles and aunties are gone, a cousin or two will reach out. I miss family. However much you love your new one, nothing replaces blood.”

CLOSING REFLECTION

Tasneem speaks without rage because she’s done the screaming already.

Her words move between theology, politics, and personal grief with the precision of someone who has examined every wound and decided to turn it into language.

Her consent proposal may disturb policymakers; her insistence on compassion may confuse activists.

But this is what courage sounds like when it refuses to be cruel. “They can excommunicate me. They can erase my name. But I will not stop speaking.”

And because she won’t stop, silence has somewhere to go.

Writer’s Note: This interview discusses experiences of female genital mutilation (FGM) and related trauma. Reader discretion is advised. The survivor’s words appear as spoken, edited only for clarity and flow. For her privacy and safety, we are not mentioning her surname or any identifying details.