|

|

In an age obsessed with speed and surface, we have forgotten how to see. Our eyes have a habit of skimming across images, screens, and faces, but rarely pause to marvel at the geometry that quietly governs beauty itself. Should we be surprised when the average adult attention span is said to be a mere 8.25 seconds? Life has always been about the journey, rather than the destination, but in our modern-day quest to attain goals, we seem to have lost perspective - that lens through which we interpret the world, shaping how we perceive truth, value, and possibility.

Over two thousand years ago Euclid defined the mathematical number phi, also known as the divine proportion or golden ratio 1.618, as the “division of a line into extreme and mean”. Centuries later, Johannes Kepler referred to it as one of geometry’s two great treasures, second only to Pythagoras’ theorem. To the ancients, phi was not a mere mathematical curiosity. Rather, it was a signature that united nature, art, and architecture. Today, however, most millennials and Gen Zs (and even a fair number of Gen Xers!) have little idea what it is, though their eyes instinctively seek it out. For what we call beauty, whether in a seashell, a face, or a cathedral is, more often than not, beauty by proportion.

Over two thousand years ago Euclid defined the mathematical number phi, also known as the divine proportion or golden ratio 1.618, as the “division of a line into extreme and mean”. Centuries later, Johannes Kepler referred to it as one of geometry’s two great treasures, second only to Pythagoras’ theorem. To the ancients, phi was not a mere mathematical curiosity. Rather, it was a signature that united nature, art, and architecture. Today, however, most millennials and Gen Zs (and even a fair number of Gen Xers!) have little idea what it is, though their eyes instinctively seek it out. For what we call beauty, whether in a seashell, a face, or a cathedral is, more often than not, beauty by proportion.

Consider a sunflower: its spiralling seeds arrange themselves in patterns that trace the Fibonacci sequence, a numerical rhythm that converges upon phi. Lilies, buttercups, pinecones, and the branching of trees follow this same pattern, each unfolding in precise mathematical harmony to capture the most light, and thus, the most life. Our DNA molecule itself, measuring 34 angstroms long by 21 angstroms wide for each full twist, conforms almost perfectly to phi, almost as if nature encoded its own geometry into the fabric of existence.

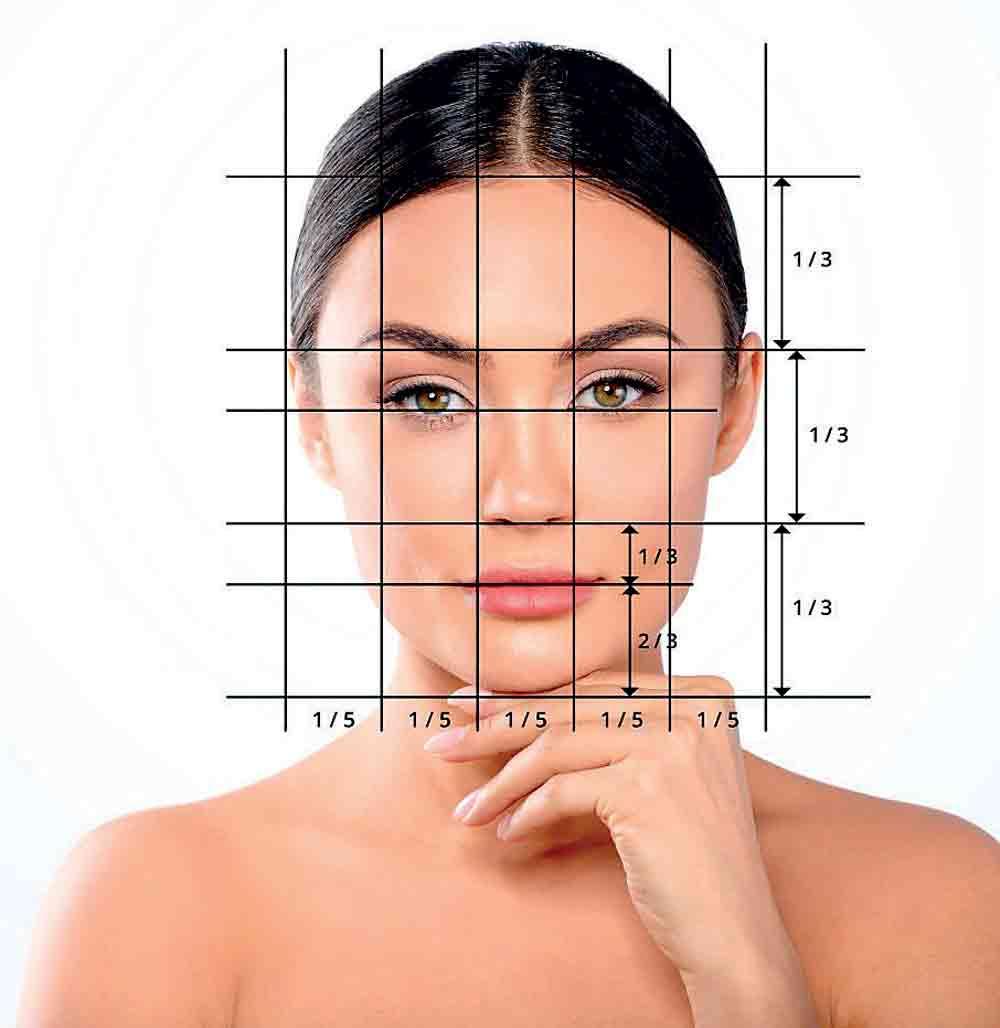

Even the human form reflects this divine measure. Anthropometric studies have shown that the height from head to navel, and from navel to floor, tends toward the golden ratio; so too do the proportions of arm to hand, or knee to navel. The faces we find “beautiful” are often those whose features most closely mirror phi. Across cultures, this perception remains constant, transcending ethnicity and era. Perhaps our ancestors were not naïve to call it divine.

The ancients understood that mathematics was not detached from art or spirit. Rather, it was a way of reading the order of the cosmos. The Great Pyramid of Giza encodes phi in the ratio between its slant height and half the length of its base. Greek sculptors and Renaissance masters embedded it in works that still arrest us with balance and serenity. It appears across music, instrument-making and composition; some of the formal boundaries of Debussy’s La mer and the placement of features on classical instruments such as Stradivarius violins have been noted to align with the same mysterious ratio. It was as if civilisation itself once acknowledged a rhythm - one that stitched proportion into the fabric of making.

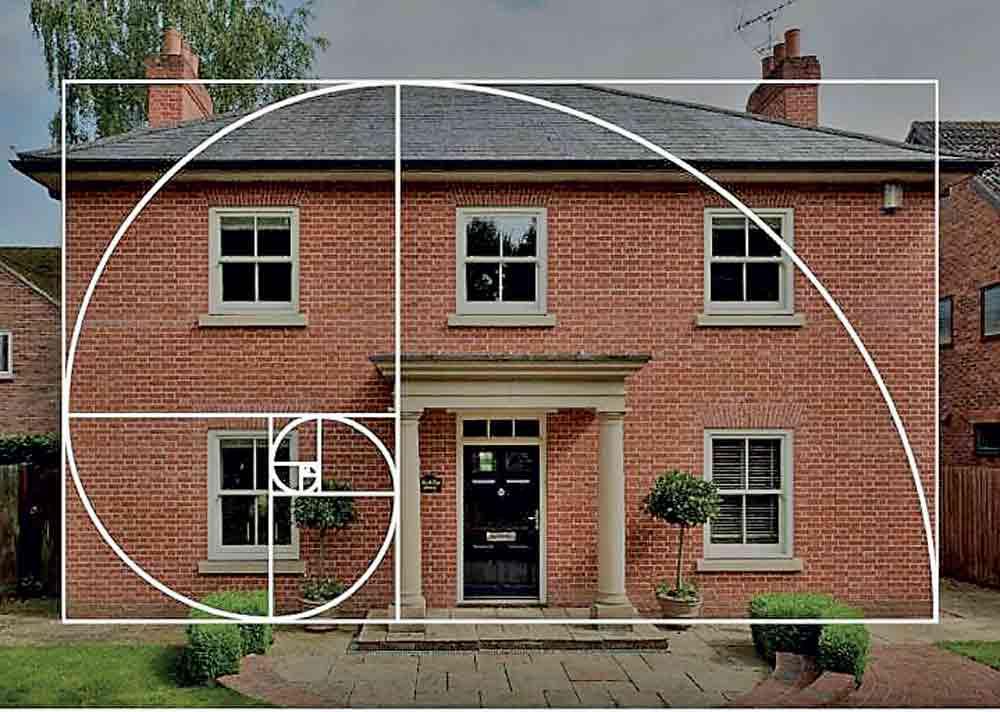

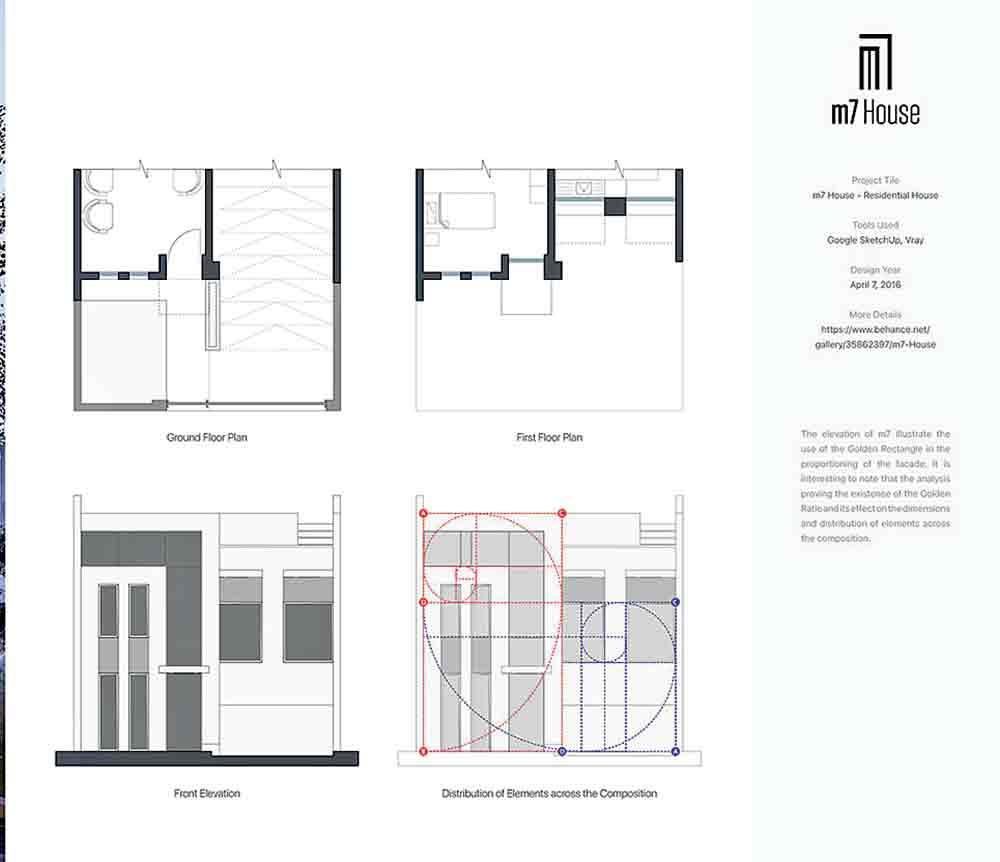

Modern architecture and design, when mindful, continue to echo this timeless geometry. The Dalian Library in China and the United Nations building in New York both demonstrate elements inspired by the golden ratio. Architects employ it not only in the overall structure of buildings but in smaller details such as window frames, façade patterns, and even staircases.

Technology, too, pays silent homage: Apple’s iPhone design is said to incorporate the golden ratio in its screen dimensions and icon grid, creating a layout that feels instinctively comfortable to the human hand and eye. Microsoft has applied phi-based ergonomic research in crafting devices that reduce repetitive strain injuries, while Tesla’s Model S showcases aerodynamic efficiency and aesthetic appeal born of golden proportions. Even corporate branding bows to this ancient constant - logos such as Apple and Twitter (bird), designed in accordance with phi, evoke visual harmony and enduring memorability, lending a distinctive identity that makes these brands timeless.

Can such awareness make a difference today? Most emphatically, yes. Phi represents more than beauty; it embodies balance. To study it is to realise that harmony is not the absence of difference but the right ratio between parts. In a world polarised by extremes, this lesson is quietly radical. When education reintroduces pupils to patterns - how petals arrange, how spirals grow, how numbers speak - we rekindle curiosity and the capacity for calibrated judgment. Students who learn to look for proportion sharpen observational skills that serve science, design, ethics, and civic life.

Moreover, appreciating phi prompts us to question wasteful habits. Nature’s forms often achieve function and economy simultaneously: spirals that pack seeds efficiently, branching that optimises sunlight, growth that scales without undue excess. If our urban planners, designers and citizens approached problems with a proportional mindset, we might favour balance over excess - sustainable choices that respect limits while optimising wellbeing.

It helps, too, to place phi alongside another foundational mathematical constant: pi, 3.142, which governs circles, spheres and curvature. Where phi speaks to proportion within growth and form, pi describes the roundness that frames those forms. Between them, pi and phi hint at the language that orders the cosmos - one constant shaping curvature, the other ordering growth within that curvature. Together they remind us that mathematics is not sterile abstraction but the grammar of life: the rules by which galaxies swirl, flowers open and faces please the eye.

This is not an argument for mysticism disguised as mathematics. Phi is not a magic formula that solves social ills. Rather it is a pedagogical treasure: a bridge between observation and analysis, between wonder and method. Teaching the golden ratio in schools invites students to connect art with algebra, biology with geometry, and ethics with aesthetics. It trains attention to proportion - an attention that, exercised in public policy and personal choices, nudges us away from extremes and toward moderation.

The ancients built monuments that endure because they built with consciousness of proportion. We might build wiser societies if we reclaim that same awareness. To teach phi is to teach a habit of seeing: that balance can be measured, that harmony can be learned, and that, in both design and daily life, proportion and perspective matter.