Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator

Ptolemy XII Auletes

Julius Caesar

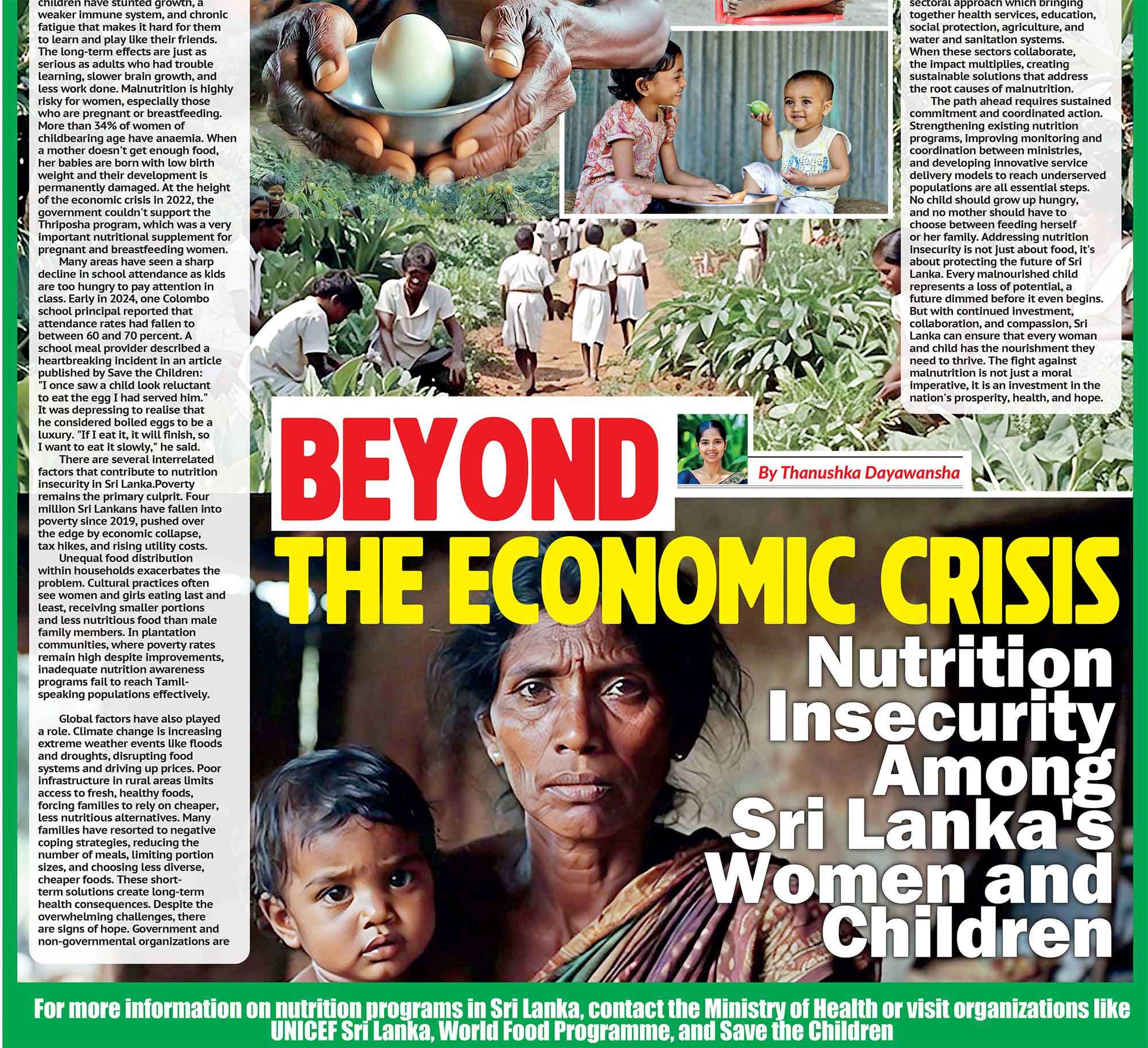

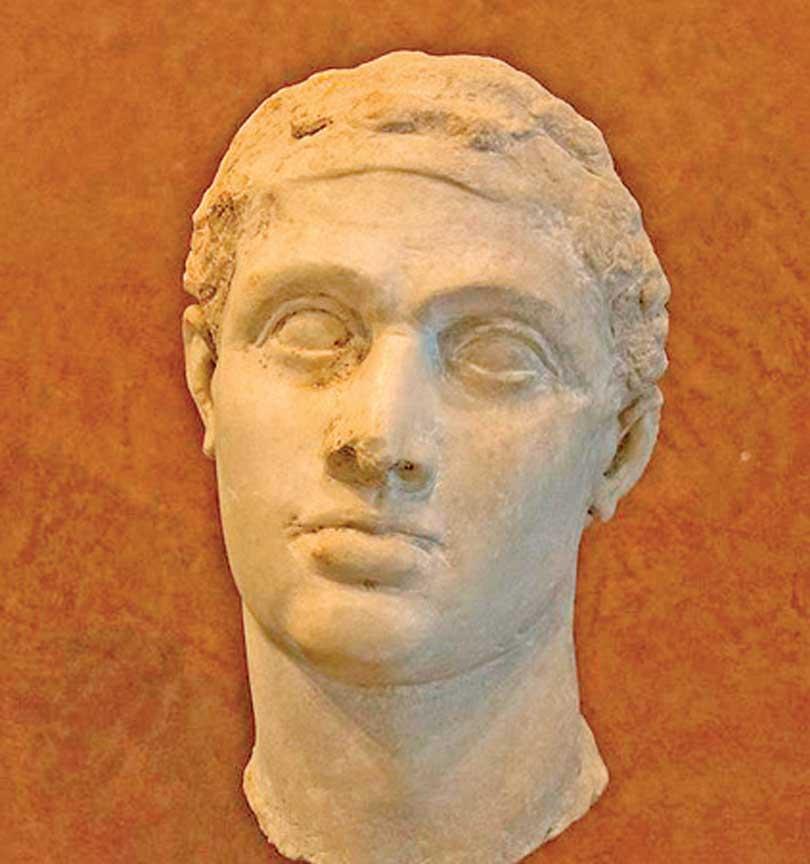

In the grand halls of history, few names echo with as much allure, controversy, and mystique as Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator, the last active ruler of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt. Born in 69 BCE and dying by suicide in 30 BCE, Cleopatra’s life was a masterclass in survival, seduction, political genius, and tragedy. But her story is far more nuanced than the often-simplified Hollywood caricature of a sultry temptress. Cleopatra was a linguist, a naval commander, a philosopher, and above all, a queen whose ambition and intelligence left a mark on history.

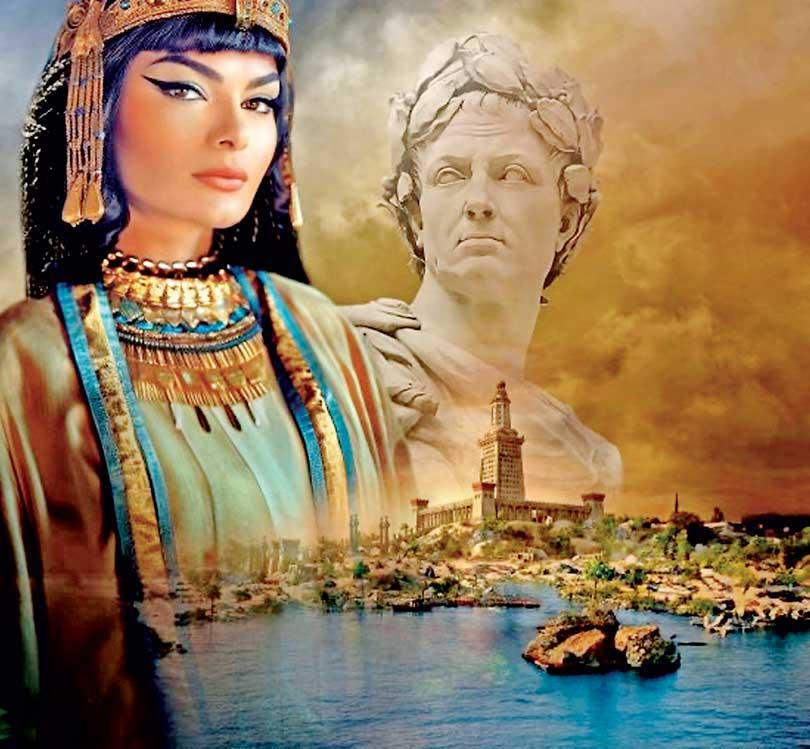

A Dynasty of Foreigners

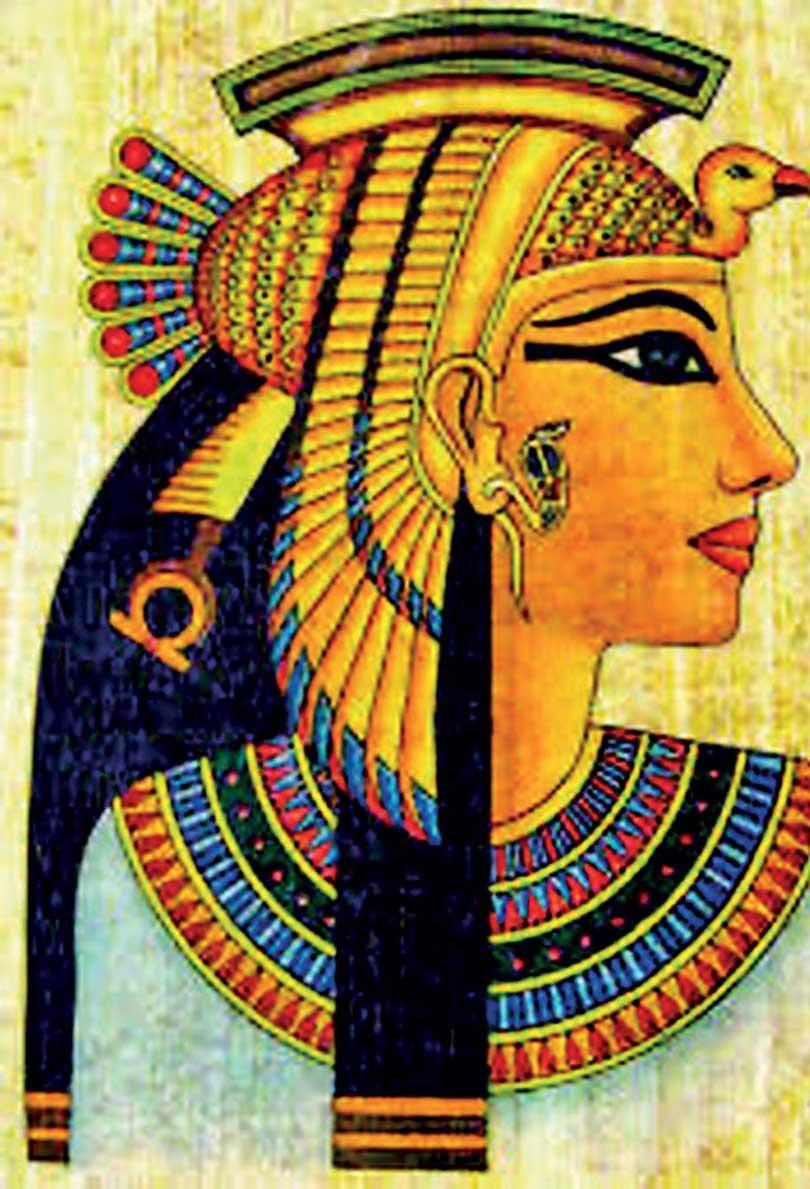

To understand Cleopatra, one must understand the unusual political setting of her reign. She was not Egyptian by blood. Cleopatra hailed from the Ptolemaic dynasty, a Greco-Macedonian royal house that ruled Egypt after the death of Alexander the Great. Her ancestor, Ptolemy I Soter, one of Alexander’s generals, took control of Egypt in 305 BCE and declared himself Pharaoh. For nearly three centuries, the Ptolemies ruled Egypt with a mixture of Hellenistic tradition and ancient Egyptian symbolism. However, most of them never bothered to learn the Egyptian language or immerse themselves in the local culture. Cleopatra was different. She was the first Ptolemaic ruler to learn Egyptian, in addition to knowing Greek and several other languages, including Hebrew, Aramaic, and perhaps even Ethiopian. This cultural sensitivity wasn’t just symbolic, it reflected her political acumen. Cleopatra wanted to be more than a foreign ruler on the Egyptian throne. She wanted to be embraced as a true daughter of the Nile.

A Young Queen in a Volatile World

Cleopatra ascended to the throne in 51 BCE at around the age of 18, initially ruling jointly with her father Ptolemy XII Auletes, and later with her younger brother Ptolemy XIII, whom she married as per dynastic tradition. However, their rule was anything but harmonious. Internal dissent, sibling rivalry, and increasing Roman interference made the Egyptian court a dangerous place. Within a few years, Cleopatra was exiled from Alexandria, fleeing to Syria and gathering an army to reclaim her throne. And then, Julius Caesar arrived in Egypt.

The Affair That Changed History

When Cleopatra learned that Caesar had come to Alexandria in 48 BCE amid the Roman civil war, she saw an opportunity. In one of history’s most theatrical moments, she is said to have smuggled herself into Caesar’s presence, rolled up in a carpet or linen sack, depending on the account. The dramatic gesture worked. Caesar was impressed, perhaps by her courage, intelligence, or her famous charm. He backed her claim to the throne, defeating her brother’s forces in the Alexandrian War. Cleopatra returned to power, and for a brief time, the Egyptian monarchy and Roman might were aligned through more than just politics; they became lovers. In 47 BCE, Cleopatra gave birth to Ptolemy XV Philopator Philometor Caesar, popularly known as Caesarion, claiming him as Caesar’s son.

Cleopatra in Rome

Cleopatra in Rome

Cleopatra visited Rome in 46 BCE, staying in a villa outside the city with Caesar and their child. The Romans, already wary of Caesar’s growing power, were scandalized. The image of an Eastern queen living like royalty in the heart of the Republic, with her son named after their beloved leader, struck many as dangerous. After Caesar’s assassination in 44 BCE, Cleopatra returned to Egypt, where she had her brother-husband killed and ruled with her young son. But the political game in Rome wasn’t over, and Cleopatra wasn’t done influencing it.

The Tragic Romance with Mark Antony

Rome plunged into civil war once more. In 41 BCE, Cleopatra was summoned by Mark Antony, Caesar’s former ally and one of the triumvirs ruling Rome. What followed was one of history’s most legendary love affairs. Antony, captivated by Cleopatra’s wit, elegance, and power, quickly became both her lover and political ally. Unlike the transactional nature of many royal relationships, theirs seemed to blend genuine affection with mutual ambition. Cleopatra hosted Antony in Alexandria, treating him to extravagant feasts and pageantry that echoed Egyptian divine kingship. Together, they had three children—Alexander Helios, Cleopatra Selene, and Ptolemy Philadelphus. However, back in Rome, this liaison was viewed as treasonous. Antony’s Roman wife, Octavia (the sister of Octavian, Caesar’s heir), had been publicly insulted. Octavian, who would later become Augustus, declared war, not on Antony, but on Cleopatra.

The Battle of Actium and the Fall of a Queen

The conflict culminated in the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, a naval confrontation off the coast of Greece. Antony and Cleopatra’s fleet was formidable but disorganized. When Cleopatra fled the battlefield with her ships, Antony followed, leaving his forces leaderless. Octavian emerged victorious. Within a year, his forces entered Alexandria. Facing inevitable defeat, Antony fell on his sword. When Cleopatra received false news of his death, she locked herself in her mausoleum. When he was brought to her, dying but not dead, he allegedly died in her arms. Cleopatra, refusing to be paraded in Octavian’s triumph as a war trophy, committed suicide, reportedly by allowing a venomous asp (Egyptian cobra) to bite her, though some scholars argue she used poison. She was 39. Her son Caesarion was captured and killed on Octavian’s orders. Egypt became a Roman province, marking the end of both the Ptolemaic dynasty and the Pharaonic era.

A Legacy of Power, Mystery, and Misunderstanding

Cleopatra’s death marked not only the fall of Egypt as an independent kingdom but also the consolidation of Rome’s imperial power. Octavian became Augustus, Rome’s first emperor. But Cleopatra’s legacy lived on, albeit in distorted forms. Roman propaganda portrayed her as a dangerous seductress who bewitched powerful Roman men and threatened the Republic. This view was immortalized in the works of Roman writers like Plutarch, Dio Cassius, and Suetonius. In the Renaissance and Enlightenment periods, she was reimagined as a tragic heroine, intelligent but doomed. Shakespeare’s “Antony and Cleopatra” portrayed her with complexity: a woman of passion and pride, defiant and majestic in her final act.

In the modern era, Cleopatra has become a symbol of feminine power, political strategy, and cross-cultural identity. She has inspired countless books, plays, films, and academic debates.

More Than a Pretty Face

One of the greatest misconceptions about Cleopatra is that her influence stemmed merely from her beauty. In reality, none of the ancient accounts described her as stunningly beautiful. What they emphasized was her charisma, intelligence, voice, and presence. Cleopatra was a Master of Diplomacy. She held her kingdom together through shrewd alliances and masterful navigation of Roman politics. She understood soft power centuries before the term existed, using wealth, spectacle, religious symbolism, and her own persona to command loyalty. She styled herself not just as queen, but as a living goddess, merging the roles of Isis, mother, ruler, and lover into one persona. This wasn’t vanity; it was political theatre at its finest.

Cleopatra Today: The Queen Reclaimed

In the 21st century, Cleopatra is being reclaimed through a more nuanced lens. Modern historians and feminists have challenged the Eurocentric, orientalist, and sexist portrayals that defined her for centuries. Was she ruthless? Yes. She had her siblings executed. She made and unmade kings. But she was also a woman in a man’s world, fighting to preserve her nation and legacy in the face of the Roman Empire’s expansion. Her story is not simply one of romance and ruin. It is a tale of agency, resilience, and complexity. Cleopatra was the last Pharaoh, but she was also the first of her kind: a global icon whose story still captivates the world.

Conclusion

Cleopatra was not merely a footnote in Roman history, nor just a queen who fell for powerful men. She was a sovereign in her own right; a ruler, strategist, linguist, and mother who fought valiantly for her people and left a legacy that endures more than two thousand years later. As we strip away the myths and examine the historical woman beneath the veils of fiction, we discover a figure far more compelling than legend ever allowed, a queen who lived on the edge of empire and shaped the course of civilization with wit, courage, and enduring power.