Picasso’s ’Nature Morte au Crane de Taureau

Di Caprio and jho low

JSelf Portrsait - ean-Michel Basquiat.j

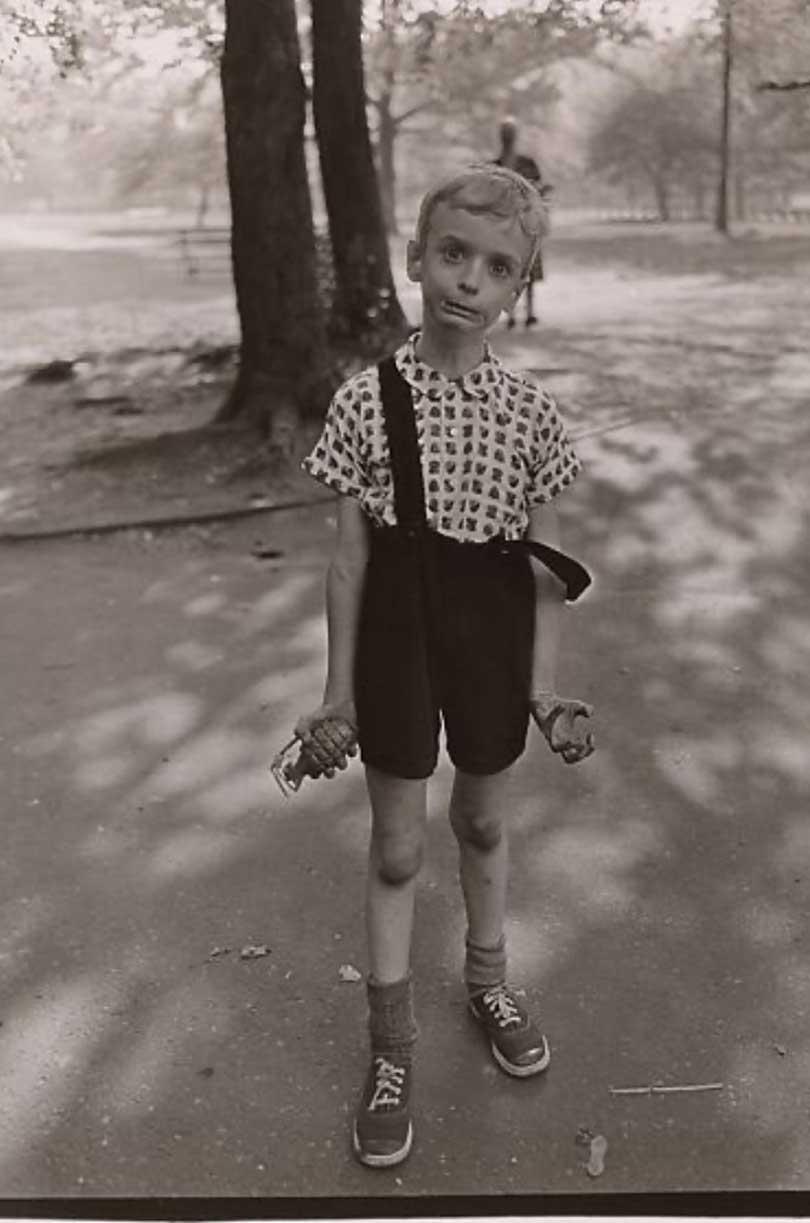

Dianne Arbu - Boy with grenades

Red Man by Jean-Michel Basquiat

“Reputation laundering” is something Colombo knows well, drop enough cash and no one looks too closely at where it comes from. Low projected an image of cultural legitimacy and sophistication. He was not just another shady money man; he was a collector with exquisitely refined taste, ingratiating himself with elite circles and embedding himself deeper into the global financial landscape.

In the rarefied air of the high-end art market, where masterpieces command millions, the sale of significant works by artists like Picasso or Basquiat is meticulously choreographed. Auction houses such as Bonhams, Christie’s, and Sotheby’s curate glamorous catalogues filled with scholarly commentary, accompanied by champagne and caviar previews, creating an atmosphere of exclusive luxury designed to push prices ever higher.

The 1MDB Scandal and Its Aftermath

It is back in the news, well, in the world of art and among those who follow it anyway, the 1MDB scandal, one of the most outrageous kleptocracy schemes in history, in which more than 4.5 billion dollars was stolen from a Malaysian sovereign wealth fund. The 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) fund was set up in 2009 by then-Prime Minister Najib Razak. The fund was ostensibly intended to stimulate Malaysia’s economic growth but ended up becoming a personal piggy bank for a group of corrupt officials and their associates, led by Low Taek Jho, better known as Jho Low. Between 2009 and 2015, billions were siphoned into a labyrinth of shell companies and offshore accounts. Using the stolen money, they purchased art, superyachts, private jets, Hollywood mansions, and lived a lifestyle that would put the Rockefellers to shame, even financing The Wolf of Wall Street, a compelling narrative

that defies logic.

Despite Jho Low’s continued evasion of capture, global investigations revealed how he deftly exploited the international art market. For him, art was not a passion but a tool for laundering money and building a veneer of respectability. Low’s purchases were enormous. In May 2013, he made a significant splash at a Christie’s charity auction organised by his “friend” Leonardo DiCaprio. Just two days later, he got into a bidding war for Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Dustheads, paying a record-breaking 48.8 million dollars. He spent 71.5 million dollars on a Mark Rothko painting from François Pinault’s personal collection. Pinault, incidentally, is the owner of Christie’s.

“Reputation laundering” is something Colombo knows well, drop enough cash and no one looks too closely at where it comes from. Low projected an image of cultural legitimacy and sophistication. He was not just another shady money man; he was a collector with exquisitely refined taste, ingratiating himself with elite circles and embedding himself deeper into the global financial landscape. He befriended Leonardo DiCaprio, to whom he gave art bought with stolen money, gifts that the U.S. Department of Justice has since recovered in its effort to return stolen funds to the people of Malaysia.

In the rarefied air of the high-end art market, where masterpieces command millions, the sale of significant works by artists like Picasso or Basquiat is meticulously choreographed. Auction houses such as Bonhams, Christie’s, and Sotheby’s curate glamorous catalogues filled with scholarly commentary, accompanied by champagne and caviar previews, creating an atmosphere of exclusive luxury designed to push prices ever higher. Yet, what transpired when four significant, recovered works of art went up for sale last month offers a sobering glimpse into the darker corners of the art world.

Their sale is being hosted by Gaston & Sheehan, on what many described as a hideously amateurish website run by a Texas-based contractor specialising in selling confiscated cars and police surplus.

The auction, open until the 4th of September, has received lacklustre bids, a “tainted provenance discount,” as some call it. Still, if you have a couple of million lying around, this might be the perfect time to pick up a Picasso. Sadly, the sale is overshadowed by the spectre of its criminal origins and marred by a process seemingly unaware of the very market it hoped to reach.

The auction features four notable works linked to Jho Low, each carrying the tragic irony of treasures turned into tools of crime. Basquiat’s Red Man One (1982), a vibrant piece reflecting the artist’s exploration of identity, was purchased by Low in March 2013 for 9.4 million dollars. The U.S. Marshals Service set the starting bid at just 2,975,000 dollars, a staggering depreciation and an uninspired opening for such a work.

Similarly, Basquiat’s Self Portrait (1982) entered the auction at 850,000 dollars, a paltry sum for a seminal work from an artist of his stature. Picasso’s Tête de taureau et broc (1939) fared no better, with its starting price obscuring its true value. Diane Arbus’s famous photograph Child with a Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park, N.Y.C. originally sold for 750,000 dollars but now has a current bid of only 10,000 dollars.

The 1MDB scandal lays bare some fundamental issues within the art market, highlighting its hidden dangers. The art world is a secretive, largely unregulated domain that provides loopholes within the broader financial system.

Closer to home, rumours abound in our own art market, priceless paintings “liberated” from rightful owners and sold to “collectors,” fakes and forgeries proudly displayed in galleries across the globe, and tantrums over coveted pieces. Non-represented artists are threatened, screamed at, told they will “never work in this town” or that they will be “destroyed” – all for the audacity of creating and selling their work to make a living. The impertinence, it seems, is too much for some who not only wish to keep artists starving but actively seek to destroy them in the name of ego and control. In this self-appointed mafia of art and taste, their expertise in the art of bullying is unquestionable.

The truth about the art industry, as I have been told, is that anyone can call themselves an expert. From the horror stories recounted at dinner parties and cocktail receptions to tales told directly by artists, it is clear that many in the industry treat the artist as little more than something to be scraped off the bottom of their shoe. Artists are often regarded as inhabitants of the lower slopes of the industry who must bow before the “tastemakers.”

Yet, the same rumour mill also carries stories of new galleries opening and of a democratisation of the art scene, one no longer bound to a narrow set of viewpoints. The arts help us make sense of the world, offering new ways of thinking, feeling, and living. They inspire and innovate, and they should be celebrated in all their varied forms. But what would I know? I am a self-admitted neophyte on the subject.