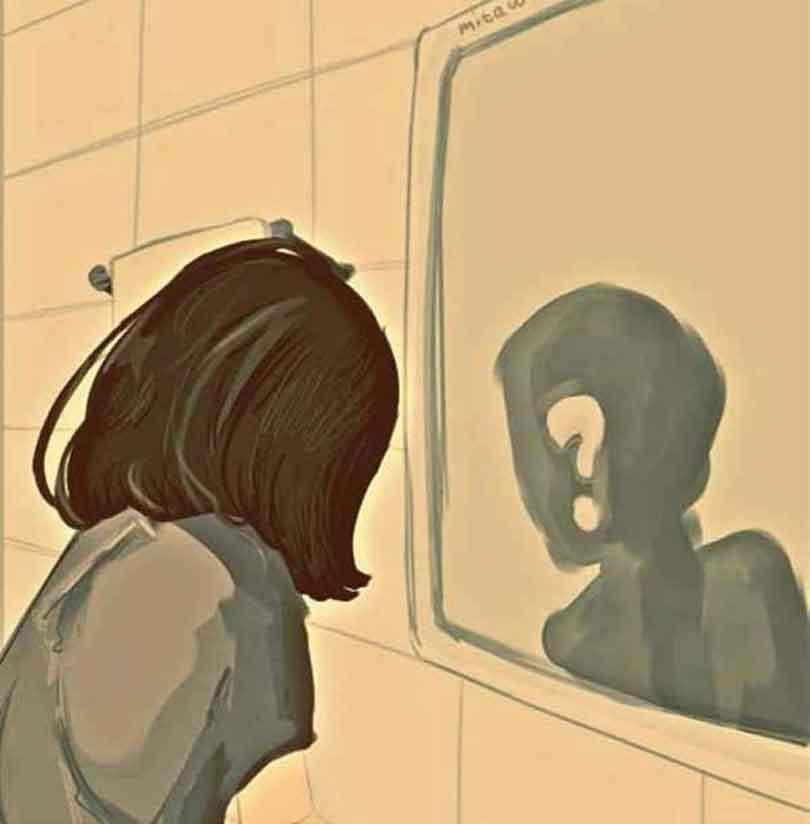

We learn early that the self is too much. Too earnest. Too frightening in its fullness. So, we learn to offer it in fragments, measured doses of laughter, rehearsed politeness, small talk fine-tuned for comfort. A smile here, a touch there. Everything becomes currency, every gesture a careful transaction. We give just enough to be accepted, never enough to be known. This is the first economy we enter, not of money, but of selfhood. Childhood teaches us to ration expression: do not cry too loudly, do not need too much, do not ask for what you cannot return. And so, the self begins to fracture. The bright, unguarded core of who we are is quietly divided, portioned out in installments that feel safe to spend.

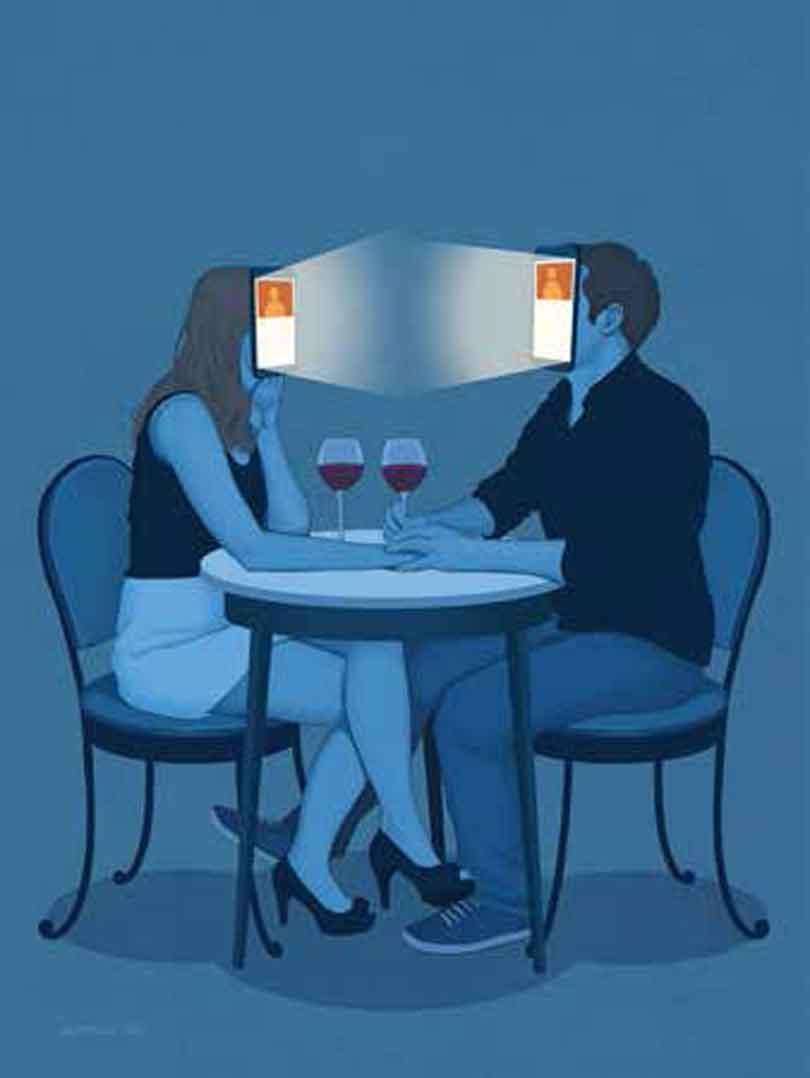

We grow into adults who manage affection like accountants. But imagine if humans were meant to be poets, not calculators. It becomes a quiet tragedy, a poet trapped inside a finance man. A text message answered within an hour feels like a small act of generosity. Not replying for hours feels like self-preservation, as though withholding attention preserves power. A hug costs emotional capital. Every “how are you?” is weighed for intent and repayment. Intimacy, once natural, turns into arithmetic. Tenderness becomes something to budget.

We live in an age that prides itself on connection, our faces illuminated by devices that promise closeness at the speed of a signal. Yet the irony persists, we have never been more reachable or more alone. Screens offer infinite access but little intimacy. We scroll through faces and bodies, each interaction an exchange, each gesture part of a social economy where affection competes with attention. It is not that we have grown colder. We have simply become careful. Modern intimacy is risk management. We are terrified of giving too much, of being misread, of loving without reciprocation. So we ration our tenderness in increments that feel rational, small enough to survive the loss if it goes unreturned.

There is a strange precision to it all. In fragments, intimacy sharpens. A glance held a moment too long, a message left unsent, a touch that feels accidental but is not, these become charged because they are rare. Desire now lives in scarcity. We have trained ourselves to feel more from less. We are the generation that feels from afar but fears commitment, calling it a “situationship” to make it sound gentler. Yet scarcity, while seductive, is exhausting. Every fraction of affection leaves behind a residue of absence, a quiet ache for what remains withheld. And so, when the day ends, we find ourselves hollow, overstimulated yet under-touched, surrounded yet unseen. The unspent parts of us wait behind locked doors, the tenderness we rationed, the need we disguised as strength, the love we parceled into manageable offerings. Then, at the end, we give ourselves a discount.

This emotional minimalism has cultural roots. For a century, intimacy has been something society alternately fears and fetishizes. The 1920s condemned flappers for their liberated bodies. The 1960s romanticized “free love” but left women with the cost of its illusions.

The 1980s turned intimacy into a site of fear through the AIDS panic. Each decade invents its own anxiety about closeness.

At first glance, today’s statistics feel paradoxical. Desire has never been less stigmatized or more accessible. Our devices offer a buffet of erotic possibility, dating apps where bodies are sorted by proximity, preferences, and prompt replies. Pornography is endless, unashamed, and free. A generation raised on sex positivity has no shortage of permission. Yet, faced with abundance, we have lost our appetite. Perhaps the problem is not sex at all, but intimacy. The two are not the same, though they often masquerade as each other. What is in recession may not be desire, but depth, the willingness to be seen fully, unfiltered, unscheduled. We have grown skilled at exposure, but not at vulnerability.

Psychologists define five dimensions of intimacy, each one a language of connection. Physical intimacy involves touch, both sexual and nonsexual, a handheld, a back leaned against, a body drawn close not for conquest but for comfort. Emotional intimacy is the sharing of truth, the kind that risks discomfort, that says, “I am not okay” and trusts the silence that follows. Intellectual intimacy is dialogue, the meeting of minds curious enough to disagree without retreat. Experiential intimacy grows from shared moments, the kind built not through confession but through living side by side, traveling, cooking, building something together. And spiritual intimacy is the rarest, a shared sense of awe, the quiet recognition that something greater holds you both.

In theory, modern life should nurture all five. In practice, it fractures them. Physical intimacy is commodified through apps. Emotional intimacy feels unsafe in a culture of self-protection. Intellectual intimacy is diluted by noise. Experiential intimacy is outsourced to content. And spiritual intimacy, wonder shared without irony, has become nearly extinct.

This fragmentation is not only cultural. For many, it is neurological. October marks ADHD Awareness Month, a reminder that fractured attention often conceals deeper emotional lives. ADHD is not simply a lapse of focus, it is the experience of living with every signal turned up, of feeling everything all at once and being told to filter it down. Many who live with it know too well the exhaustion of connection, of trying to sustain intimacy in a world that moves too fast for tenderness. Their minds and hearts often give in installments, not out of choice, but out of survival.

What remains is performance. We curate relationships as we curate social feeds, precise, pleasing, filtered through algorithms of approval. Our ever-desperate end-of-month photo dump, a highlight reel disguised as truth. And I am no exception, an addict of it myself. We are not dishonest, but we are edited. In the editing, something vital disappears. The raw, untranslatable immediacy of connection gives way to the safer, more legible version of it.

If we are living in installments, it may be because wholeness feels unbearable. To love without restraint, to reveal oneself entirely, is to invite loss in its purest form. And so, we pay in fractions. We sell only what we can afford to lose. Yet there are moments when the system fails, small ruptures in the ledger. A conversation that stretches past midnight.

A shared silence that feels like understanding. A laugh that turns into confession. These are not transactions, they are collisions. And they remind us that intimacy, in its truest form, cannot be calculated. It is irrational, generous, and entirely human.

We may never abandon our caution; modernity makes it difficult to. But perhaps the rebellion lies in offering without tally, in speaking without rehearsal, in allowing ourselves to be known in real time. Intimacy, after all, is not the loss of control. It is the trust that what we give will not destroy us. Maybe reclaiming life begins there, with the courage to give without counting, to touch without strategy, to be seen without flinching. To fall in love not with perfection, but with presence. To live, at last, without installments. But I have come too far, and perhaps I will not try it. Maybe someone else will start.