In the late 1980s, during the second JVP insurrection, a number of schoolboys in Embilipitiya were abducted by state-linked forces. These students were allegedly targeted for suspected involvement with the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna. Many were never seen again

Not in some faraway land, but here in our own nation, Sri Lanka, an island in the Indian Ocean, lies a history that is both complex and deeply painful. These are not stories from distant wars. They are wounds carved into our own soil. For decades, Sri Lanka has grappled with ethnic tensions, political turmoil, and violent conflict that have left deep and lasting scars. Among the many dark chapters that haunt our national conscience, two incidents remain particularly disturbing: the Embilipitiya disappearances and the Bindunuwewa massacre. These were not foreign atrocities. They happened here, in our neighbourhoods, involving our people, under our watch. While these events occurred in different contexts and time periods, they are connected by a pattern of ethnic discrimination, abuse of power, and a systemic failure to deliver justice. They are powerful reminders of the deep-rooted issues Sri Lanka continues to ignore.

Embilipitiya: Disappearances and Denial

In the late 1980s, during the second JVP insurrection, a number of schoolboys in Embilipitiya were abducted by state-linked forces. These students were allegedly targeted for suspected involvement with the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna. Many were never seen again. Although not driven by ethnic conflict, the Embilipitiya disappearances revealed the terrifying ease with which the state could violate the rights of its citizens. The victims were mostly Sinhalese. The lesson was clear. When power is unchecked, no community is truly safe. These disappearances were not isolated acts. They were part of a larger pattern of extrajudicial killings and forced disappearances that swept through the country during periods of political unrest. The culture of impunity that followed sent a dangerous message. That some lives simply do not matter.

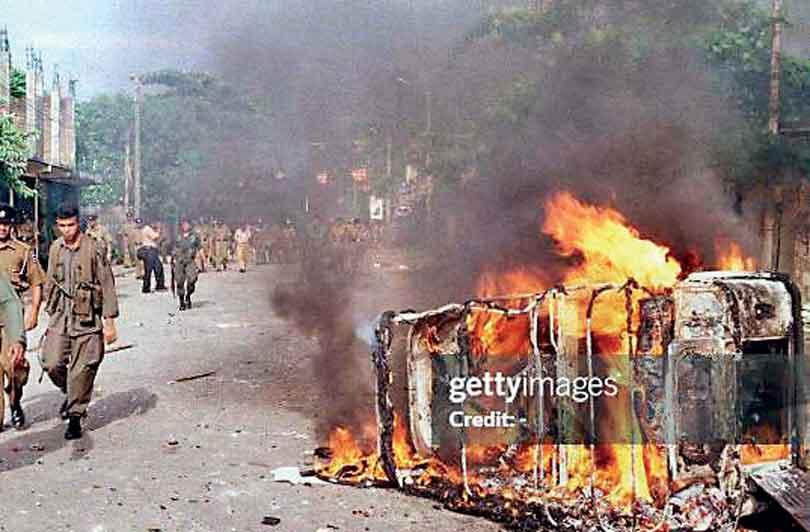

Bindunuwewa: Hatred with a Witness

On October 25, 2000, a mob of Sinhalese villagers attacked the Bindunuwewa detention centre in Bandarawela. The victims were 26 Tamil detainees, many of them youth, being held under the Prevention of Terrorism Act. Most had not been charged with any crime. Some were preparing for release. Despite prior warning signs, police officers stationed at the centre failed to protect the detainees. As the mob stormed the facility, officers stood by or fled. What followed was a massacre. The brutality of the attack was compounded by the failure of the justice system. Even with eyewitness accounts and video evidence, initial court proceedings led to acquittals. Only after public pressure and appeals were some convictions secured. The delay and reluctance to prosecute those responsible reflected a justice system that too often protects perpetrators and abandons victims.

A Pattern We Refuse to Break

While the Embilipitiya and Bindunuwewa massacres differ in their details, they share disturbing similarities. Both incidents reflect a failure to protect the vulnerable. Both expose the role of state actors who either participated in or turned a blind eye to violence. Both point to a wider culture of impunity that has taken root in Sri Lankan society.

Ethnic tensions have long been manipulated for political gain. For decades, political actors have inflamed division for short-term power. Communities have been turned against each other, and violence has been justified through fear, misinformation, and hate. Meanwhile, state complicity in violence has become a recurring theme. Whether through direct participation or passive inaction, state institutions have failed to uphold justice. Perpetrators walk free, while victims and their families are left without answers, let alone healing.

A Society Conditioned to Forget

One of the most disturbing legacies of these massacres is the silence that follows them. Our collective memory is short. National mourning rarely leads to national accountability. There is a pattern in Sri Lanka. Outrage, followed by silence. Grief, followed by denial. The massacres at Embilipitiya and Bindunuwewa should have served as turning points. Instead, they became footnotes in a history book few want to open. We fail to teach these stories. We fail to discuss them. And by doing so, we fail to prevent them from happening again.

The Path Forward: Justice, Not Amnesia

Sri Lanka cannot move forward without confronting its past. Establishing a truth and reconciliation commission to investigate historical atrocities, including Embilipitiya and Bindunuwewa, would be a meaningful step toward healing. Reforming the justice system is equally urgent. Laws must be strengthened to ensure crimes against humanity and ethnic violence are prosecuted. Judges, lawyers, and police must receive training to handle such cases with integrity and sensitivity. Systems must be put in place to protect witnesses and support victims. Community-based reconciliation efforts are essential. Dialogue between ethnic groups, led by survivors, educators, and civil society leaders, can foster understanding and trust. Psychological support and trauma counselling must be available to those affected by violence. Education and awareness are key. Schools should teach the truth about Sri Lanka’s history. Public campaigns should promote empathy, inclusion, and coexistence. A generation raised on truth is a generation less likely to repeat violence.

Learning from the Past, Building the Future

The Embilipitiya and Bindunuwewa massacres remind us of the devastating consequences of silence, hatred, and inaction. They are not just stories from the past. They are warnings. And if ignored, they will be repeated. When we say “never again,” we must mean it. That means refusing to forget. Refusing to excuse. And refusing to normalize state violence in any form. Sri Lanka must confront its painful history with courage and clarity. Only by doing so can we build a society where every citizen is safe, every victim is remembered, and every future is free from the horrors of our past.