An appeal to bring home a treasure that is truly a part of our nation’s legacy

Time and again nations from all over the world demand the return of cultural treasures stolen from them. These artifacts are often housed in distant museums which are completely disconnected from the communities whose histories they embody. The people to whom these treasures belong lack the financial and logistical means to access them. The relevance of these pieces is immeasurable since they have the unique ability to tell stories, especially in terms of revealing the past and making people aware of their ancestors.

Time and again nations from all over the world demand the return of cultural treasures stolen from them. These artifacts are often housed in distant museums which are completely disconnected from the communities whose histories they embody. The people to whom these treasures belong lack the financial and logistical means to access them. The relevance of these pieces is immeasurable since they have the unique ability to tell stories, especially in terms of revealing the past and making people aware of their ancestors.

As we already know - Greece has been calling for the return of the Elgin Marbles. The Nigerian government has made numerous requests for the Benin Bronzes to be repatriated. Egypt continues its efforts to get back the Rosetta Stone and the Council of Elders from Easter Island have asked the British government to return Hoa Hakananai’a, a seven-foot basalt statue stolen and gifted to Queen Victoria without the permission of those to whom it belongs.

As we already know - Greece has been calling for the return of the Elgin Marbles. The Nigerian government has made numerous requests for the Benin Bronzes to be repatriated. Egypt continues its efforts to get back the Rosetta Stone and the Council of Elders from Easter Island have asked the British government to return Hoa Hakananai’a, a seven-foot basalt statue stolen and gifted to Queen Victoria without the permission of those to whom it belongs.

These priceless treasures often carry with them the histories of their countries of origin. They tell stories of how they were created or how they came to be, they reflect the cultures from whence they came and reveal the truth about the past. Most importantly they help future generations to understand their heritage and genealogy. These ‘works of art’ initiate discussions and debates related to the stories about their creation. They could also reveal a clear narrative which helps to preserves their legacies, promote understanding and bring a sense of healing.

But what if there is a treasure that was never stolen? What if this ‘piece of art’ was recently created by a person whose ancestry connects them to a part of our diaspora? And what if this treasure is something that exists in time and space? What if such a piece transcends physical boundaries and allows its immense value to be felt only as a shared experience between performers and audience? Do we have the right to demand that it is brought to the very land that its most relevant to?

After having seen the extraordinary play ‘Counting and Cracking,’ I am convinced that it is a profoundly valuable work of art which holds a deep significance to our land and its history. I am therefore making an appeal for this piece of theatre to be brought to our shores as its relevance is paramount.

‘Counting and Cracking’ was written by Sydney-based playwright and storyteller S. Shakthidharan, who is of Sri Lankan Tamil heritage.

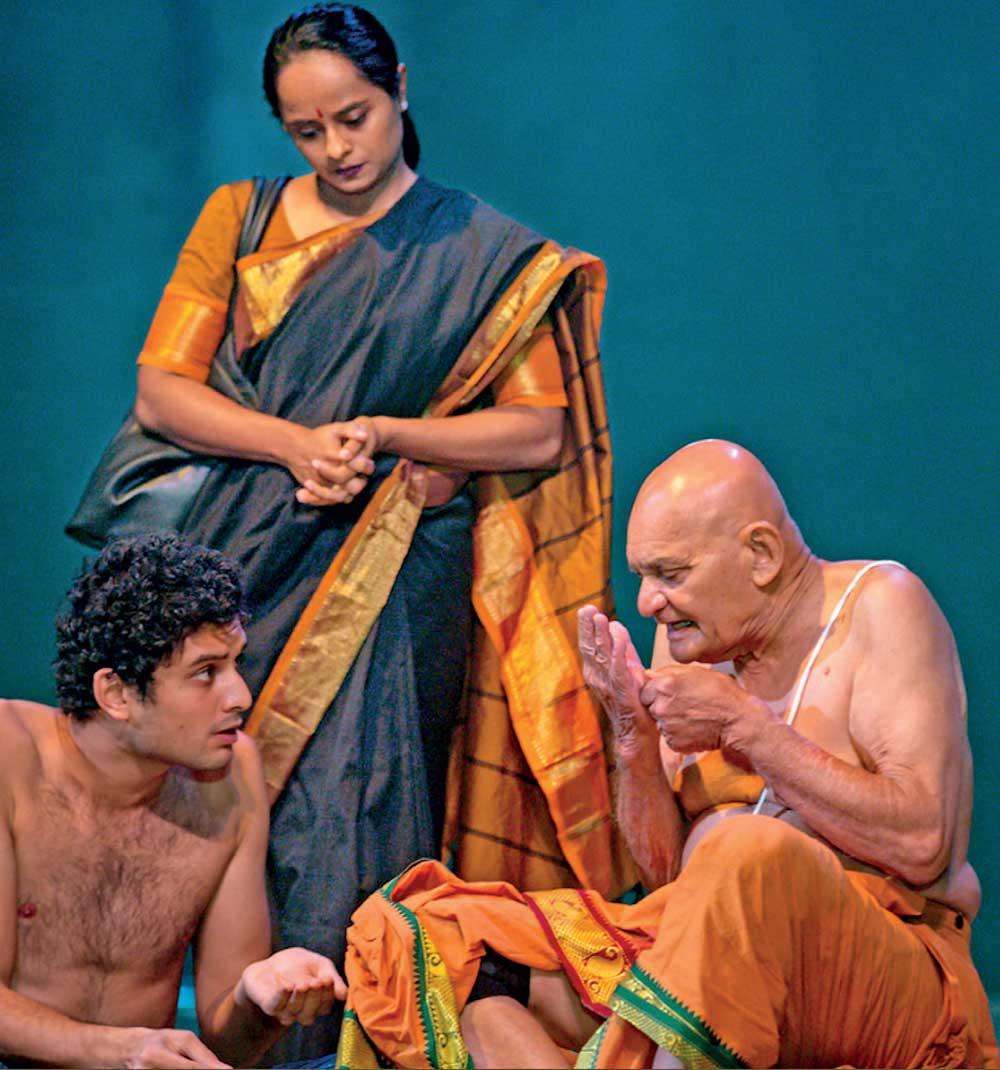

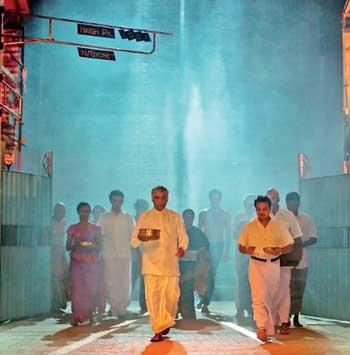

I had the privilege of seeing this play at the Skirball Theatre NY last September and was overwhelmed by its power, honesty, and sheer theatrical magic. Running at a length of 3 hours and 45 minutes this play managed to grip the audience and take them on a thoroughly informative journey about one of the most terrifying periods of our island’s history. The astute direction by Eamon Flack, who is credited as the associate writer of this piece, made the action flow seamlessly. The continuous flow of energy on the stage and the dialogue which incorporated a mixture of English, Sinhalese, Tamil and even some Turkish, was a reminder of the mayhem of languages that all of us shift between when we are totally at ease in an environment, we call home. The beautiful yet simple and relatable sets and costumes incorporated into this piece made every scene even more relevant to anyone from Sri Lanka. The invaluable artistic advice from the playwright’s mother – the famous Bharatha Natyam dancer, Anandavalli – was crucial to the visual aspects that enhanced the action accurately as the play developed. Her subtle and effective choreography, the beautifully toned costumes and the musical accompaniment gelled together so perfectly that it was exhilarating.

This play, which was originally performed at the Sydney Festival in 2019, has since been performed in major cities around the world including Birmingham, Edinburgh, Melbourne, and New York. It is indeed a pity that only a handful of Sri Lankans have seen this hugely important work. Its story offers an important lesson about understanding our country’s brutal history from both sides of the conflict. It is critically important for future generations, especially since survivors rarely speak of these events and others still carry personal biases shaped by their individual experiences.

The 1983 riots tore the fabric of our country apart like never before. Since this harrowing time, those of us who call ourselves Sri Lankan have subconsciously hitched our wagons to one side or the other - and this includes me. The relative peace we enjoy is still quite uneasy. We smile, we kiss, and we greet one another and break bread together, but we remain acutely aware of the varied fault lines between us. For example, there are, friends who fundraised for the LTTE, those who provided the government with arms - those who played one side against the other and made huge profits while doing so, others who claimed they stood for human rights but prolonged the war while lining their pockets and there were downright racists on both sides; and the list goes on. However, after decades of conflict and economic hardship, it has become evident that fostering peace and communal unity is the sole path to achieving any meaningful prosperity. It is therefore essential that we have such stark reminders about the suffering, trauma, and injustices that our people, Tamil and Sinhalese alike, endured for decades.

When I heard about ‘Counting and Cracking’ I was intrigued about how the subject of the civil war in Sri Lanka would be approached as a piece of theatre. My inquisitiveness was raised further by my ongoing disgust with the BBC for its continuously biased reporting of any conflict around the world (especially this one) and the LTTE propaganda machine which did its best to tarnish the reputation of the Sinhala people as die-hard racist!

I entered the theatre ready to tear apart anything that seemed fabricated, untrue or even remotely fictional and what I witnessed was the undiluted truth of how much suffering was placed upon those caught between ruthless terrorists, power hungry politicians and opportunist who make money out of human suffering.

The play felt like a history lesson, cleverly exploring political issues that turned the main characters into pawns. It highlighted the key events that shaped the situations each character had to deal with. These were: the call for a separate state of Eelam, the rash and shameful decision made by J. R Jayawardene which initiated the 1983 riots, S.W.R.D Bandaranaike’s Sinhala only policy which set alight the flames of separatism, the innocent Tamil people caught up in a vortex of racism which had developed since independence, Sinhalese people who risked their lives helping their Tamil neighbours by shielding them, the forced fundraising by the LTTE that took place in every country that the diaspora had taken refuge in, the parasites who used the war to acquire property and make money, young Tamil’s who became terrorist after witnessing the suffering of their family members, rudderless young Sinhalese men with a lack of prospective futures who joined the army seeking some form of meaning for their existence, innocent men who were held in detention camps, displacements, disappearances and divisions.

From a human perspective the plot also dealt with love, relationships, sorrow, shame, hardship, survival, fear, hope, and joy. It touched on how traditions are confronted by new ways of thinking.

The play begins with a Tamil boy who trying to understand the rituals that his cultural background demanded of him, and it develops gradually with him discovering how he came to be in Australia. While discovering the deep-rooted traditions of his people, the storyline expands to describe the causes that led to his family being displaced.

It also had enchanting little touches that reminded many of us about the fast-disappearing quaintness of the Sri Lanka we left behind. Households that had loyal servants from other cultural backgrounds, rituals that we observe during births, marriages and deaths, the vegetable vendors who used to come to our gates daily, places and streets that still exist, familiar phrases and exclamations that we use when we are back with family and friends, the strong bonds we forged with our neighbours, the respect with which we honoured our elders and our ingrained obedience to authority.

There were also some particularly endearing and recognizable character portrayals too. Chiefly among them was the role of the minister who strives to bring order and common sense to government decisions as the country begins to fracture. But my favourite character was the fire breathing dragon of a grandmother who is also the typical/ traditional Tamil wife. The accuracy of this particular characterisation is universally truthful – the finger wagging harridan with a sharp tongue who has her hands firmly on the purse strings – she controls everything and everyone around her. Do they love her or fear her? The decision is for you to make. However, one thing is for certain – even her husband, the confident, erudite, ball-breaking minister is reduced to dithering mess when confronted by her. One must admit that we have all encountered the likes of her at some stage in our lives.

I have heard through the grapevine that several organizations have made serious efforts to bring this play to Colombo, but the cost of flying in, hosting and paying a cast and crew of around forty people would be prohibitively expensive. It would have been far more feasible had more Sri Lankan actors accepted the roles offered to them when the play was being cast, but unfortunately, they declined. This still presents a valuable opportunity for the Ministry of Culture to step in and provide support, or for a philanthropically minded businessperson to help make it happen. Whatever decisions are made about this issue they must be made now; before the urgency of this play fades from our minds and disappears into the dust, never to be performed again. The only way it will live on is if we bring it home.