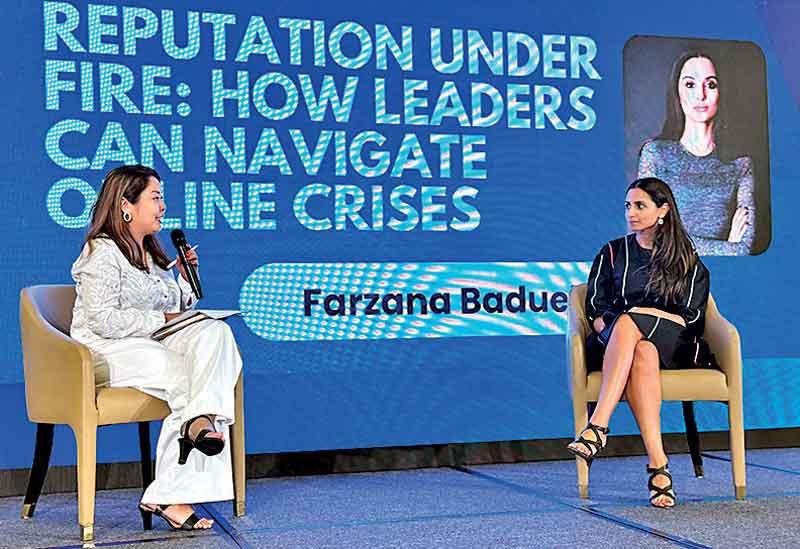

Travel teaches you things no classroom can. Not just about countries, but about yourself. When I arrived at the Sheraton in Colombo, to speak on risk, resilience and crisis communications, I expected earnest professionals and polite questions. What I found instead was something rarer; a room full of people who understood that reputation is infrastructure. I had come to address the Public Relations Association of Sri Lanka, a newly formed professional body representing the country’s communications industry. I met board members, agency heads, corporate strategists and media practitioners. None were selling vacuous optimism. All were building capacity. In a world awash in noise and distrust, they grasped something essential: how a nation explains itself to its citizens, to investors, to the world is no longer peripheral. It is foundational. This matters far beyond public relations.

Travel teaches you things no classroom can. Not just about countries, but about yourself. When I arrived at the Sheraton in Colombo, to speak on risk, resilience and crisis communications, I expected earnest professionals and polite questions. What I found instead was something rarer; a room full of people who understood that reputation is infrastructure. I had come to address the Public Relations Association of Sri Lanka, a newly formed professional body representing the country’s communications industry. I met board members, agency heads, corporate strategists and media practitioners. None were selling vacuous optimism. All were building capacity. In a world awash in noise and distrust, they grasped something essential: how a nation explains itself to its citizens, to investors, to the world is no longer peripheral. It is foundational. This matters far beyond public relations.

WHAT PR REALLY IS AND WHY IT COUNTS

Public relations remain one of the most misunderstood professions. Many reduce it to spin or press releases. In truth, good PR is about responsibility. The Chartered Institute of Public Relations defines it as the strategic management of information between an organisation and their publics. It is the planned and sustained effort to establish and maintain goodwill and mutual understanding between an organisation and its publics.

STRIP AWAY THE JARGON: PR IS HOW INSTITUTIONS EARN AND SUSTAIN TRUST.

It differs from marketing and advertising in crucial ways. Advertising is paid attention. Marketing solely sells products. Public relations protects and builds reputation: the asset you rely on when there is no ad to hide behind, when scrutiny peaks and certainty vanishes. In crisis, PR is not cosmetic. It is existential. It is how you behave when the stakes are highest, how you communicate with clarity and empathy, how you rebuild trust brick by brick. That is why PR has become indispensable globally. The industry is now worth roughly $20 billion worldwide and growing, not because organisations love consultants, but because the risks are sharper. Fragmented media, stakeholder capitalism, geopolitical instability, climate shocks, AI disruption, misinformation traveling faster than truth. Reputations that once took decades to build can now collapse in hours. Reputation risk is no longer occasional. It is constant.

WHY PROFESSIONAL ASSOCIATIONS ARE NATION BUILDING

This is where bodies like PRASL matter. Professional associations are not social clubs. They set standards, define ethics, invest in skills, create collective accountability. They ensure that those shaping narratives understand the weight and consequence of that power.

Sri Lanka has long had PR practitioners. Until now, it lacked a national association bringing the profession together. PRASL changes that. It signals maturity. It tells the world that Sri Lanka treats communications not as a function, but as a discipline. For a country whose reputation directly affects tourism, exports, investment and diplomacy, this is strategic. The ability to tell your own story rather than having it told for you is a form of sovereignty. Professional associations also level the playing field. They allow smaller nations to develop homegrown communicators who understand local context, culture and history, rather than outsourcing narrative control to external voices with thin insight.

With Mushtak Ahmed, President, PRASL

LIVING IN PERMANENT CRISIS

My talk in Colombo focused on crisis communications. But crisis is no longer the exception. It is the environment. We live in what analysts now call a state of permanent crisis: digital shocks, political upheaval, climate emergencies, economic volatility, collapsing trust. Leaders must respond instantly. Every response is scrutinised, archived, weaponised. Silence reads as avoidance. But reacting too fast, without facts, alignment or empathy, can trigger a second crisis harder to control than the first. Sri Lankan communicators understand this tension intimately. Responsible communication requires judgment: knowing when to speak, when to pause, how to balance transparency with accuracy. These are skills that can be taught, tested, refined. That is why professional development and ethical frameworks matter.

MY UNLIKELY PATH

I did not set out to work in public relations. I studied accounting and math, then left university before finishing my degree. Like many in their early twenties, I did not yet know who I was or where I belonged. Throughout my twenties, I ran a tax business. On paper, it succeeded. Internally, I felt adrift. It took years to realise that success without purpose is hollow. I later joined a political party as vice chairman of its business forum. Politics was intellectually intoxicating but emotionally exhausting. I realised I did not want to be a frontline politician. I preferred working behind the scenes, shaping strategy, not delivering slogans. At the time, the Conservative Party leader was David Cameron, himself a former PR professional. Watching perception, leadership and communication shape political reality was transformative. I grasped then that perceptions do not merely reflect reality. They create it. Political communications is an intense training ground. It teaches you that words have consequences and trust, once lost, is agonizingly slow to rebuild.

BUILDING A GLOBAL PRACTICE

In 2009, my co-founder James and I launched Curzon PR. Sixteen years later, the profession still surprises me daily. PR sits at the crossroads of psychology, media, neuroscience, geopolitics, design, technology and human behaviour. It is demanding, fast moving, deeply human. Our work spans continents. We have advised over fifteen governments including Canada, Finland, Spain and Qatar. We have counselled government backed initiatives, major real estate developers, technology companies operating in the space sector. We have worked with NGOs and think tanks such as the Johns Hopkins Washington based Foreign Affairs Institute. All of this work requires an intercultural lens when crafting and delivering global strategic communications.

I am British, born and raised in London, with parents who migrated from Kashmir in Pakistan. Growing up as part of a minority teaches you to read the room early, to listen carefully, observe power dynamics, understand what goes unsaid. That outsider perspective becomes an advantage. It sharpens perception. In global communications, where nuance determines success or failure, that sensitivity is invaluable.

My Husband and I with the Former Prime Minister of Great Britain, David Cameron

WHY RESPONSIBILITY DEFINES OUR ERA

Every year, global risk reports list misinformation and disinformation among the gravest threats facing societies. Communications professionals are not observers of this risk. We are on the frontline. Responsible communications is not optional. It is a duty. Professional associations must lead here, championing ethics, transparency, accountability. They must help practitioners navigate AI, deepfakes, algorithm driven outrage. They must invest in media literacy and critical thinking. Sri Lanka’s success with professional qualifications in fields like accountancy shows there is appetite for rigor and excellence. Communications deserves the same respect. PRASL’s formation suggests Sri Lanka understands that credibility is built, not claimed.

A COUNTRY FINDING ITS VOICE

Nation building is not only about infrastructure and GDP. It is about institutions, trust, voice. It is about who tells the story and how. Sri Lanka sits at a complex geopolitical crossroads, rebuilding economically while navigating global power dynamics and digital scrutiny. In such a world, strategic communication is not cosmetic. It is central to resilience. Leaving Colombo, I felt hopeful, not because the challenges are small, but because the foundations are being laid. Professional associations rarely make headlines. But they shape outcomes, build capacity quietly and persistently. In a world saturated with noise, trust has become the most valuable currency of all. Sri Lanka’s investment in its communications profession is an investment in that trust.

About The Writer

Farzana Baduel, President of the Chartered Institute of Public Relations and CEO and Co-founder of Curzon PR (UK) is a leading specialist in global strategic communications. She advises entrepreneurs at Oxford’s Said Business School, co-founded the Asian Communications Network (UK), and serves on the boards of the Halo Trust, and Soho Theatre. Recognised on the PRWeek Power List and Provoke Media’s Innovator 25, she also co-hosts the podcast, Stories and Strategies. Farzana champions diversity, social mobility, and the power of storytelling to connect worlds.