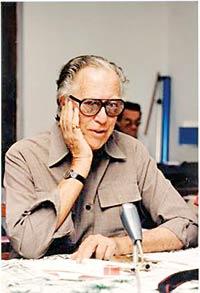

Colombo is a city under constant metamorphosis. Day to day, nothing seems to change. In fact, it can be frustratingly mundane. But suddenly, amidst the chaotic streets, the blanket of humidity and the occasional smog, you look up, and everything is different. Once fondly referred to as ‘the garden city of Asia’, over the years, Colombo has slowly lost that reputation. Skyscrapers are always shooting up; these unnatural, steel structures tower above and cast the world below into cool, dark shadows. Our city, with its lush open green spaces, is no more. It is gradually becoming cramped and dull. However, there is one person who had a different vision for Sri Lanka – Geoffrey Bawa. One of the pioneers of Tropical Modernism, Bawa, believed buildings should be made in context with their natural surroundings. Instead of constructing buildings that can be found anywhere in the world, using styles and materials alien to the island, Bawa’s buildings are a reflection of Sri Lanka – her styles, beauty and traditions. So, on what would have been his 106th birthday, let’s look back and take a journey through Bawa’s Colombo.

Colombo is a city under constant metamorphosis. Day to day, nothing seems to change. In fact, it can be frustratingly mundane. But suddenly, amidst the chaotic streets, the blanket of humidity and the occasional smog, you look up, and everything is different. Once fondly referred to as ‘the garden city of Asia’, over the years, Colombo has slowly lost that reputation. Skyscrapers are always shooting up; these unnatural, steel structures tower above and cast the world below into cool, dark shadows. Our city, with its lush open green spaces, is no more. It is gradually becoming cramped and dull. However, there is one person who had a different vision for Sri Lanka – Geoffrey Bawa. One of the pioneers of Tropical Modernism, Bawa, believed buildings should be made in context with their natural surroundings. Instead of constructing buildings that can be found anywhere in the world, using styles and materials alien to the island, Bawa’s buildings are a reflection of Sri Lanka – her styles, beauty and traditions. So, on what would have been his 106th birthday, let’s look back and take a journey through Bawa’s Colombo.

Number 11

The streets of Colpetty are always a buzz. Buses overflowing with people race one another, while tuk-tuks and motorbikes weave their way through the everyday mayhem. But there’s one quiet corner just off Bagatalle Road where time seems to have stood still. Nestled at the end of a cul-de-sac on 33rd Lane, Geoffrey Bawa’s Colombo residence is the physical manifestation of his creativity. The third bungalow in a set of four, the architect initially rented the space from Harold Peiris in 1959. Within a decade, Bawa had purchased all four bungalows and began his transformation.

The space is full of light and movement, it expands and contracts as you meander through. Narrow passageways open up into sunlit courtyards, and artwork from Bawa’s private collection breathes life into the space. Batik murals adorn the walls, while artefacts have been thoughtfully placed to accentuate the building’s features, and on every floor, nature seeps into the building. The home’s tranquil setting makes you forget that you’re within a bustling city. To visit the property, you can book ahead and join one of their daily guided tours, or the Bawa Trust also gives out the two rooms for guests to stay.

The Parliament Complex

Although it’s not technically in Colombo, the Parliament complex in Kotte is one of Bawa’s most renowned works. In 1979, plans to build a new parliament commenced, and Geoffrey Bawa was chosen to design the building, which was declared open in 1982. Set on an island within Diyawanna Oya, the complex looks as though it floats on the murky waters. Throughout his career, Bawa rejected the grandiose styles of colonial architecture. Tropical Modernism quickly became associated with a newly independent Sri Lanka. The parliament complex is a fine example of this as it seamlessly blends with its surroundings, rather than dominating them. The parliament also pays homage to Sri Lankan vernacular architecture. The teak copper-lined roofs echo the Kandyan tradition, while the asymmetrical complex with its long driveway is reminiscent of ancient palatial structures. Bawa’s Parliament design is perhaps a reflection of what he believed governance could look like– transparent, open, in rhythm with nature.

De Saram House

Being one of the most influential figures in Sri Lankan architecture, it’s no surprise that Bawa was sought after by people who wanted him to design their homes. Throughout his 46-year-long career, Bawa designed numerous residential properties, but one property that stands out is the De Saram house in Ward Place. In 1986, Druvi and Sharmini de Saram chose Bawa to renovate and expand their two small houses. Druvi de Saram was an acclaimed pianist, and the house was designed with its music room at its center. In 2019, the Geoffrey Bawa Trust took over management of the house and worked closely with the de Sarams to restore it to its former glory.

The house is an urban oasis; bougainvillaea bushes heavy with flowers coil over the mango yellow wall, and courtyards dotted with Araliya trees and jasmine vines fill the air with sweetness. Apart from restoring the property, the Trust also undertook the conservation and display of artworks. Pulling pieces from the de Sarams’ private collection, as well as the Bawa art collection, the artwork is beautifully displayed in the music room where Druvi’s grand piano stands silently. As with Number 11, you can book a guided tour of the de Saram house through the Trust’s website.

Seema Malaka Temple

During the 1950s and 60s, most of Bawa’s Western counterparts saw a building as a closed unit and sought to keep everything out. However, Bawa and other architects like Minette de Silva designed to bring the outside in and let the inside out. Water was often used as a design feature, rather than being viewed as a hindrance. Situated on the matcha-tinted Beira Lake, Bawa redesigned this meditation pavilion in 1976. Inspired by the ancient forest monasteries of the Ritigala and Anuradhapura, as well as certain Kandyan features, Bawa created a temple that was one with nature. A large bodhi tree grows at the centre of the main pavilion, which is encircled by Buddha statues in different mudras. Despite being in the heart of Colombo, when you visit the Seema Malaka, you feel as though you’re far away from all the hustle and you can finally enjoy a moment of peace. While visiting the temple is a must, I recommend walking to the opposite side of the lake and enjoying the view of the temple against the ever-changing Colombo skyline.

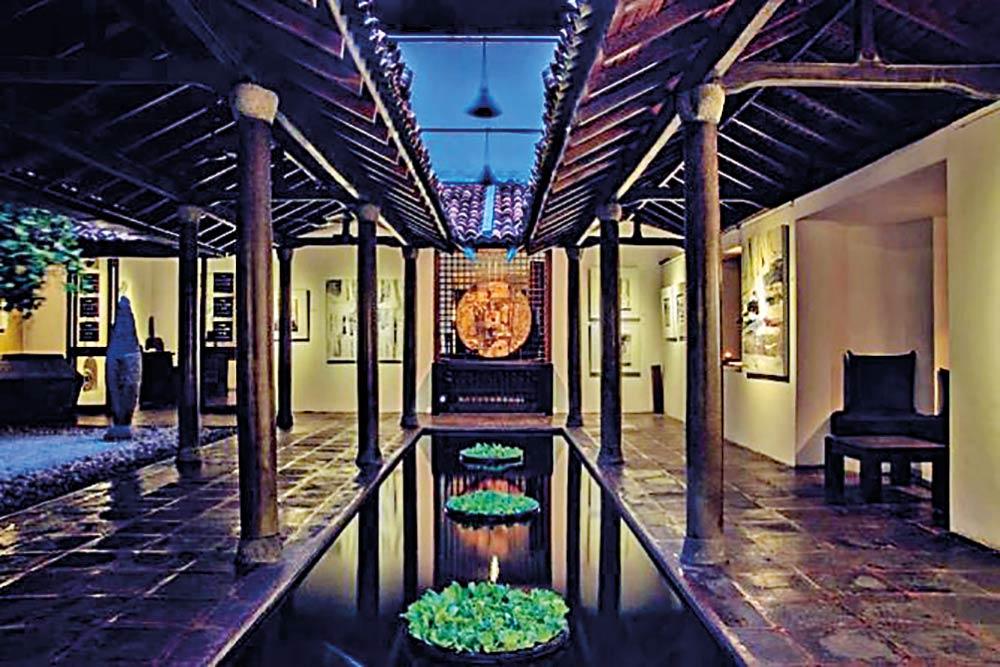

The Gallery Café

The Gallery Café is a Colombo institution. Known for serving fiery tamarind chillie martinis and the most decadent chocolate cake, as well as being a thriving art gallery that hosts a variety of interesting exhibitions. The building was once the office of Bawa’s architecture firm, and you can see his influence etched into every corner. As soon as you walk through its large archway and into a courtyard shrouded by Araliya trees, it is clear you’re entering a Bawa property. While the space may have evolved over the years, it still remains a hub for Sri Lankan creativity and artistic expression.

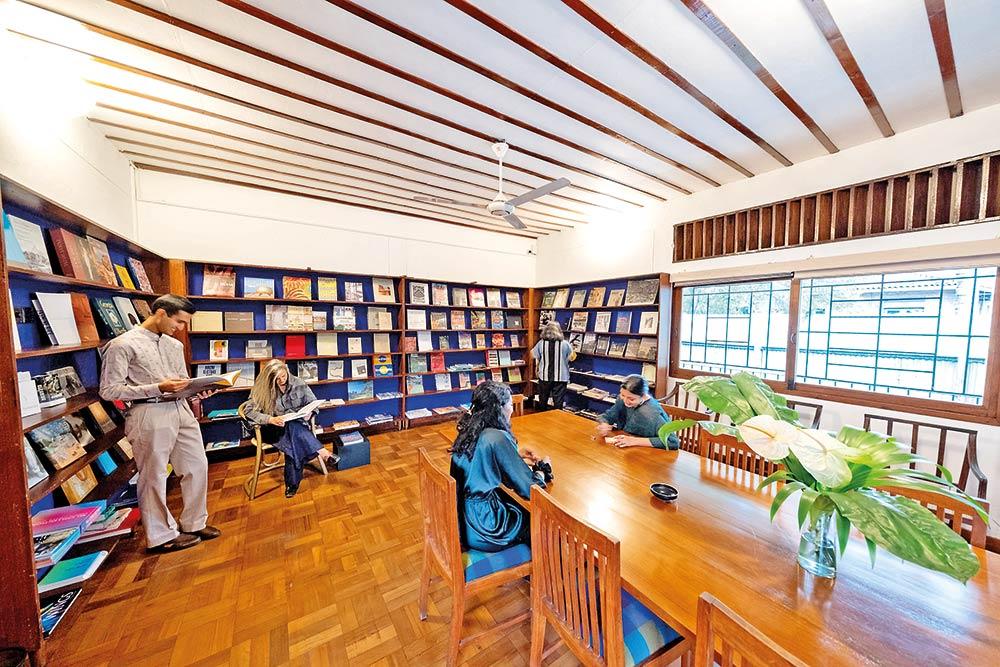

The Bawa Space

Finally, the Bawa Space is perhaps one of the architect’s lesser-known residential projects. Down a small lane off Horton Place, the property was designed and built between 1959-61 for lawyer Aelian Kannangara. Although the building takes up most of the tight property, Bawa’s design, with floor-to-ceiling glass doors, twin atriums and open spaces, makes it feel expansive. The Geoffrey Bawa Trust now uses the building as their offices, but it also has an open-plan gallery space, a design store (originally the living and dining spaces), as well as an extensive library and airy terraces on the second floor. If you’re interested in visiting the Bawa Space gallery, it is open Wednesday through Saturday from 12-6 p.m., and the Trust regularly hosts talks and events at this location.

Colombo today might feel like it is changing rapidly, racing ahead, becoming more ‘modern’, losing its green. But in these Bawa spaces, time folds. They remind us that modernity doesn’t have to mean erasure; architecture can be both progressive and rooted in tradition. That even in a city constantly evolving and obsessed with sleek glass buildings, these pockets of peace can be created, if we’re willing to bring the outside in.