By: Yashmitha Sritheran

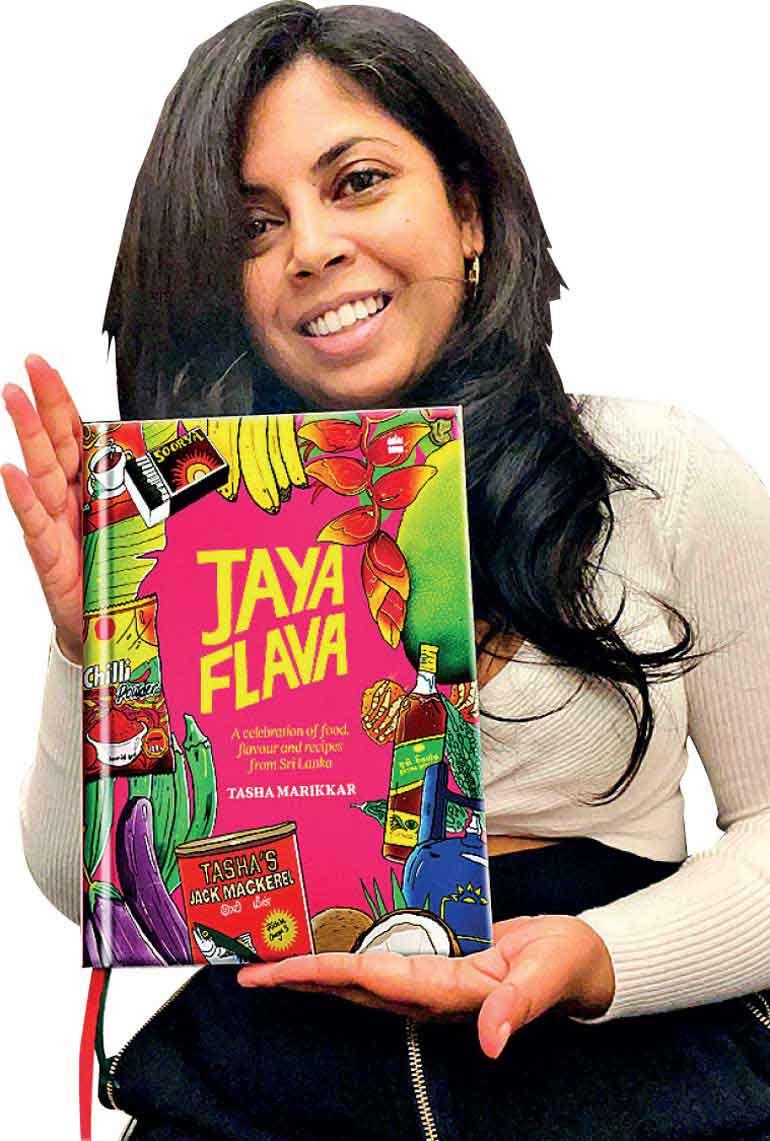

For decades, Sri Lanka has been sold to the world through postcard images of palm-fringed beaches and colonial-era charm. But beneath the glossy travel brochures lies a far more complex, layered and exhilarating story, one told through food, people, history and everyday life. Jayaflava: Celebrating Sri Lanka, a new six-part culinary travel series hosted by Sri Lankan-born, cookbook author, Tasha Marikkar, and directed by award-winning filmmaker Afdhel Aziz, sets out to tell that story on Sri Lanka’s own terms. Part food show, part travelogue, part cultural portrait, the series journeys across the island from Colombo to Jaffna, Hiriketiya to Puttalam and Galle, using six iconic dishes as entry points into conversations about identity, heritage, resilience and modern Sri Lanka. More than a television series, Jayaflava is a love letter to a nation reclaiming its narrative through creativity, cuisine and cool. Launching on National Geographic India, the series arrives at a pivotal moment for Sri Lanka. Global interest in the island’s food and culture is surging, and Jayaflava positions the country not simply as a destination, but as a living, evolving cultural force.

Reframing the Island

At its heart, Jayaflava challenges the familiar imagery that has long defined Sri Lanka abroad. Instead of leaning into nostalgia or tourist clichés, the show captures electric tuk-tuk rides through Jaffna, late-night street food rituals in Colombo, coconut arrack tastings on the south coast and conversations with chefs, artists and writers shaping a contemporary Sri Lankan identity. Each episode focuses on a single dish such as kottu, hoppers, crab curry or lamprais, using it as a lens through which to explore a region and its people. The result is a textured portrait of a country that is multicultural, inventive and unapologetically modern. Tasha Marikkar, who spent much of her life between Sri Lanka and the United Kingdom, brings an intimate perspective to the series. Drawing on her Colombo Moor, Colombo Chetty and Sinhalese heritage, she approaches each location not as a visitor but as someone rediscovering home. “I wanted to create a Sri Lankan cookbook and now a television series that finally felt like the Sri Lanka I actually grew up in,” she says. “Messy, multicultural, funny, generous and full of flavour. So much of what the world sees is a postcard version of the island. Jayaflava is the real one.” Her cookbook, published by HarperCollins, laid the groundwork for the show’s culinary focus. After four years spent researching and reinterpreting traditional recipes, Tasha’s mission remains simple: to teach the world how to cook Sri Lankan food and to love it as deeply as she does.

Cinematic Storytelling

Behind the camera, Afdhel Aziz brings a distinctly cinematic eye. The Los Angeles–based director is known for his acclaimed documentary on architect Geoffrey Bawa, and his ability to blend art, design and social history into compelling visual narratives. With Jayaflava, he applies that same sensibility to food and travel. “This is not just a food show,” states Afdhel. “It is a story about identity, resilience and the joy of rediscovering home. We wanted to present Sri Lanka as we see it, modern, multicultural and magnetic.” The series moves from the bustling streets of Colombo to the northern city of Jaffna, the surf towns of the south coast, the coconut plantations of Puttalam and the historic port city of Galle. Along the way, viewers meet chefs, mixologists, artists and writers who are shaping contemporary Sri Lanka, and experience the flavours and stories that make the country impossible not to love.

The Six Dishes, The Six Stories

The structure of Jayaflava is deceptively simple. Six episodes, six dishes, six destinations. But each chapter functions as a cultural essay in motion.

Episode One: Kottu – Colombo

Sri Lanka’s most beloved street food becomes the soundtrack to Colombo’s nightlife, featuring BBC DJ and author Nihal Attanayake, visits to iconic late-night spots like Pilawoos and Aluthkade, and conversations with contemporary artist Vicky Shahjahan.

Episode Two: Hoppers – South Coast and London

The dish that carried Sri Lankan cuisine to the global stage is explored alongside Chef Karan Gokani of London’s renowned Hoppers restaurant, linking diaspora identity with culinary export.

Episode Three: Arrack – Hiriketiya

Booker Prize-winning author Shehan Karunatilaka joins Tasha to unpack Sri Lanka’s iconic coconut spirit, alongside modern beachside dining at Smoke and Bitters, part of Asia’s 50 Best.

Episode Four: Crab Curry – Jaffna

Featuring Chef Dharshan Munidasa of Ministry of Crab, the episode explores Tamil culture, post-war resilience, and the cultural weight of perfecting crab curry.

Episode Five: Coconut – Puttalam

From family kitchens to live-fire dining, the coconut becomes a symbol of both sustenance and identity.

Episode Six: Lamprais – Galle

Dutch colonial influence, Muslim heritage and layered food history converge in the iconic banana-leaf parcel, featuring Chef Tama Carey and food influencer Kamal Uncle.

Together, the episodes sketch a contemporary cultural map of Sri Lanka; one that balances nostalgia with reinvention.

A Pivotal Cultural Moment

The timing of Jayaflava is not accidental. Global interest in Sri Lankan food and travel has surged in recent years, with search interest in “Sri Lankan food” and “Sri Lanka holiday” rising sharply in the UK alone. The show’s initial broadcast on National Geographic India positions Sri Lanka within a wider South Asian tourism and culture conversation, reaching millions of travel-curious viewers across the region. Backed by major Sri Lankan hospitality and tourism brands, including Cinnamon Hotels and Resorts, Mastercard and Flying Ravana Adventure Park, the series functions not just as entertainment but as cultural diplomacy, reframing Sri Lanka as a destination defined by creativity, complexity and contemporary cool.

But perhaps its most important audience is Sri Lankans themselves. In telling a Sri Lankan story through Sri Lankan voices, Jayaflava quietly challenges decades of externally framed narratives. It asserts that the island’s stories are best told by those who live them.

The Jayaflava Guide to Sri Lanka will initially air on National Geographic India on Friday nights at 8:00pm (reaching an estimated 17 million people in India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and the Maldives) and is in the process of being sold to major channels in the UK, US, Europe and Australia.

In Conversation with Tasha Marikkar

You’ve lived between Sri Lanka and the UK for much of your adult life. How has navigating these two cultures shaped the way you understand Sri Lankan food and identity today?

Living in the UK from the age of 18 gave me distance from Sri Lanka in a way I didn’t expect. That physical distance created emotional clarity. When you grow up somewhere, you don’t always stop to analyse what feels normal, it’s only when you leave that you begin to see what’s unique about your own culture. Being away from Sri Lanka made me miss the everyday rituals of food; the smells of tempering spices, the way meals are shared, the rhythms of home kitchens. At the same time, returning to Sri Lanka over the years allowed me to see how dynamic and fast-moving the food scene really is. There’s this myth that Sri Lankan cuisine is fixed in time, that it belongs in our grandmothers’ kitchens and doesn’t evolve. But being between the UK and Sri Lanka helped me understand that our food is constantly shifting. It absorbs influences from migration, from global food trends, from different ethnic and religious communities living side by side. Sri Lankan cuisine is often spoken about as if it’s one thing, but it’s actually a beautiful mix of many things. There are regional differences, family differences, cultural differences. My own heritage reflects that complexity, and moving between cultures has helped me embrace the idea that Sri Lankan food is plural, layered and always in conversation with the world.

You started cooking very young. What first sparked that passion?

I was definitely one of those kids who spent a lot of time watching television because both my parents worked long hours. One of the shows I became obsessed with was, If Yan Can Cook, So Can You. I’d watch it religiously and then run into the kitchen to try and recreate whatever I’d just seen. Of course, I had no idea what I was doing most of the time, but that curiosity stayed with me. What I realise now is that food became a form of companionship for me. Cooking filled time, but it also gave me a sense of independence and creativity. It wasn’t just about following recipes; it was about experimenting, messing things up, and slowly learning that food could be a way of expressing myself. Growing up in Sri Lanka, food is always around you. You’re constantly watching aunties cook, family friends sharing recipes, neighbours sending plates of food across fences. Even if you don’t realise it at the time, you’re being trained by osmosis. That environment definitely planted the seeds for what would eventually become my career.

Jayaflava began as a cookbook and has now become a television series. What was the original idea behind it, and how did your personal experiences shape what Jayaflava became?

At the beginning, my instinct was to make Jayaflava quite academic. I wanted to break down Sri Lankan food through a very analytical lens; its history, its anthropology, its influences. But I was encouraged to loosen up and let it be more energetic, more playful and more reflective of real life. The name itself came from a mix of musical inspiration and the celebratory meaning of the word “Jaya,” which is about victory, joy and affirmation. Over time, Jayaflava became a way for me to describe the spirit of Sri Lanka as I experience it; the colour, the chaos, the humour, the warmth, the contradictions. Sri Lanka isn’t neat or easily packaged. It’s loud, emotional, layered and sometimes messy. Jayaflava embraces that. It’s about telling food stories that don’t pretend everything is perfect but still celebrate the joy and creativity that comes out of our kitchens, our streets and our communities. What’s important to me is that Jayaflava doesn’t just archive food traditions, it shows them as living, breathing things. Recipes change. People reinterpret dishes. New voices come in. That fluidity is what makes Sri Lankan food culture so exciting.

Bringing a Sri Lankan-made food series to National Geographic India is a major milestone. What did that journey look like behind the scenes, and what did it mean to finally get the show commissioned?

Honestly, it was a long and emotionally demanding process. The show took around two years to come together, and there were plenty of moments where it felt like it might never happen. There were rejections, delays, funding challenges, and lots of creative reworking. With my co-creator and director Afdhel Aziz, we kept refining the concept over and over again. Every time someone said no, we would go back and ask ourselves how to make the story stronger, clearer and more compelling. Eventually, we found partners who believed in the vision and helped us bring it to life. Seeing it land on National Geographic felt surreal. For me, it wasn’t just about professional validation, it was about the fact that a Sri Lankan story, told by Sri Lankans, was being platformed on a global channel. That representation matters. It changes who gets to be seen as an authority on our own culture. It also felt deeply personal. There were moments when I wondered if the story I wanted to tell was “global” enough or “marketable” enough. Getting the green light reminded me that authenticity is the thing that travels the furthest.

The series clearly goes beyond food. How did you approach capturing Sri Lanka’s people, traditions and everyday life through the lens of cuisine?

Food is just the doorway. Once you step through it, you’re really talking about people, memory, identity and belonging. Every dish in Sri Lanka is tied to a story, about where it comes from, who cooks it, when it’s eaten, and why it matters. When we were filming, I was very conscious that we weren’t just showcasing recipes. We were meeting families, artists, writers, chefs and everyday people who embody different sides of Sri Lanka. Through them, you start to understand how food connects to religion, geography, migration and even politics. What I love is that food equalises people. You can have deep conversations with someone over a meal in a way that might feel awkward in any other setting. The camera becomes less intimidating when you’re chopping onions together or eating with your hands. That intimacy allowed us to capture moments that felt honest rather than staged. Ultimately, the show is about community. It’s about showing that Sri Lanka’s diversity is not something abstract, it’s something you can taste, smell and share at the table.

Looking back on the entire filming journey, what were the moments that stayed with you the most?

There were so many moments, but two really stand out. One was a very playful, slightly chaotic adventure sequence that ended up showing my real personality more than I expected. It was funny to film, and even funnier to watch back. I realised that it was okay to not be polished all the time; that vulnerability can be part of storytelling. The second was travelling to Jaffna for the first time through the lens of the show. That experience was emotional. Jaffna carries so much history and pain, but also so much resilience and creativity. Being there, meeting people, eating their food and listening to their stories shifted something in me. It reminded me how important it is to tell stories from places that are often reduced to headlines rather than lived realities.

The kite festival sequence was visually stunning but looked chaotic. What was that experience actually like on the ground?

Chaotic is the perfect word. There were around 20,000 people there, and we were stuck in traffic for hours just trying to get close to the site. Once we arrived, we realised we couldn’t even bring in our main cameras because of crowd control restrictions. A lot of what you see on screen was captured on phones and drones, which forced us to be really flexible. In some ways, that limitation helped. The footage feels raw and immersive because we had to work with what we had. Behind the scenes, it was stressful, but it was also a reminder of what Sri Lanka is like in real life; crowded, noisy, unpredictable and full of energy. That chaos is part of the country’s rhythm, and I’m glad the show didn’t try to smooth it out.

Finally, what do you hope audiences take away from Jayaflava?

For Sri Lankans, I hope the series sparks pride. I hope people see themselves reflected on screen and feel that their everyday lives, their food and their stories are worthy of being documented beautifully. I also hope it encourages more Sri Lankans to tell their own stories, whether through food, film, writing or any other creative medium. For international audiences, I want Jayaflava to challenge the narrow image of Sri Lanka as just a beach destination. The country is layered, complex and culturally rich. There are histories, tensions, joys and contradictions that make it far more interesting than any postcard version could capture. If people come away feeling curious, curious enough to cook Sri Lankan food, to learn more about the country, or even to visit with a more thoughtful lens, then I feel like the show has done its job. More than anything, I hope it reminds people that stories told with honesty and heart can travel across borders.