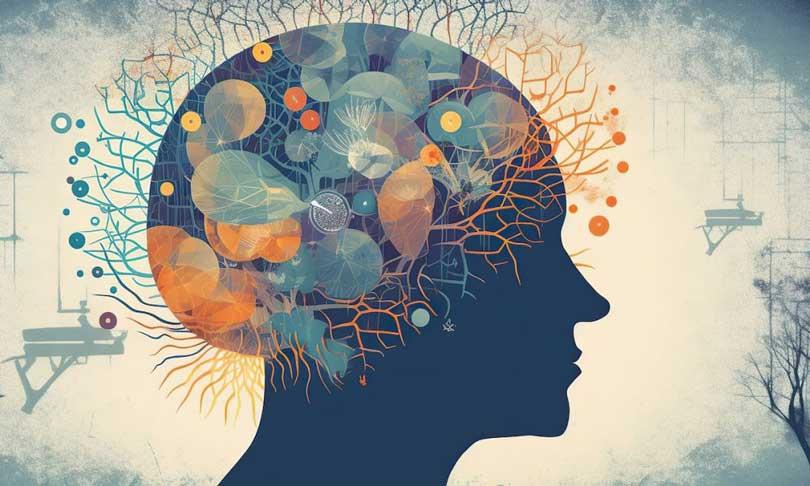

Human beings are neurologically wired for connection. Social interaction is not merely a psychological preference it is a biological necessity. When isolation becomes prolonged, the brain does not remain unchanged. Research over the past several decades has shown that long-term social isolation can alter brain structure, stress responses, cognition, and emotional regulation in measurable ways.

The Brain Interprets Isolation as a Threat

According to neuroscientist Dr. John Cacioppo, whose research at the University of Chicago helped pioneer the modern science of loneliness, the brain processes prolonged social isolation similarly to physical danger. When individuals experience sustained loneliness, the brain activates threat-detection pathways, particularly in the amygdala the region responsible for processing fear and vigilance. This heightened alert state increases sensitivity to negative social cues. In simple terms, the brain becomes more defensive. Over time, this persistent activation can reinforce anxiety and social withdrawal, creating a feedback loop where isolation deepens.

Structural Changes in the Brain

Studies using brain imaging have shown that chronic isolation can affect gray matter volume in regions associated with emotional regulation and cognitive processing. Research published in Nature Communications in 2020 found that individuals who reported high levels of loneliness showed structural differences in the default mode network a system of brain regions involved in self-reflection and social thinking. These changes may explain why prolonged isolation often increases rumination and overthinking. Additionally, animal studies have demonstrated that extended social isolation can reduce synaptic connections in the prefrontal cortex, the area responsible for decision-making, impulse control, and complex reasoning. While human brains are more resilient, similar patterns of reduced cognitive flexibility have been observed in chronically isolated individuals.

Impact on Memory and Cognitive Function

Long-term isolation does not only affect mood it may influence memory. According to research published in The Journals of Gerontology, socially isolated older adults have a significantly higher risk of cognitive decline and dementia. One proposed mechanism involves reduced cognitive stimulation. Social interaction challenges the brain: it requires interpretation of facial expressions, tone, language, and emotional context. Without these regular cognitive exercises, neural networks involved in memory and executive function may weaken over time. Furthermore, chronic stress hormones particularly cortisol play a role. Prolonged isolation elevates cortisol levels. According to the American Psychological Association, sustained high cortisol exposure can impair the hippocampus, the brain region central to memory formation.

Emotional Regulation and Mood Disorders

Isolation has a profound relationship with depression and anxiety. The World Health Organization has repeatedly identified social isolation as a major risk factor for mental health disorders. Neurobiologically, long-term loneliness alters serotonin and dopamine signaling neurotransmitters involved in mood regulation and reward processing. When social reward pathways are underused, motivation and pleasure responses can diminish. This may explain why individuals experiencing prolonged isolation often report emotional numbness or lack of interest in activities they once enjoyed. Moreover, a large-scale study published in The Lancet Psychiatry following COVID-19 lockdowns found increased rates of depressive symptoms among individuals experiencing extended social separation. Researchers concluded that the absence of routine interpersonal interaction significantly affected emotional stability.

Increased Stress Response and Inflammation

The brain and immune system are closely connected. According to research from UCLA’s Social Genomics Lab, chronic loneliness can alter gene expression in immune cells, increasing pro-inflammatory activity. From a neurological perspective, this matters because inflammation affects brain function. Neuroinflammation has been linked to mood disorders, fatigue, and impaired concentration. In other words, the psychological experience of isolation can translate into biological stress responses throughout the body.

Sleep Disruption

Isolation also interferes with sleep regulation. Studies have shown that lonely individuals experience more fragmented sleep. According to findings published in Psychological Science, social isolation is associated with reduced sleep efficiency and increased nighttime awakenings. Sleep is essential for neural repair, emotional processing, and memory consolidation. Disrupted sleep further compounds cognitive and emotional difficulties, intensifying the effects of isolation on the brain.

Why Isolation Feels Physically Painful

Neuroimaging research has shown that social rejection activates similar brain regions as physical pain, particularly the anterior cingulate cortex. This overlap explains why loneliness is often described as “painful.” The brain does not sharply distinguish between social and physical threats both are interpreted as risks to survival. Long-term isolation does not simply affect mood; it reshapes the brain’s stress systems, emotional circuits, and cognitive networks. While solitude in moderation can be restorative, prolonged social disconnection carries measurable neurological consequences. As modern lifestyles increasingly reduce face-to-face interaction, understanding the brain’s need for connection becomes not just a psychological insight, but a public health priority.