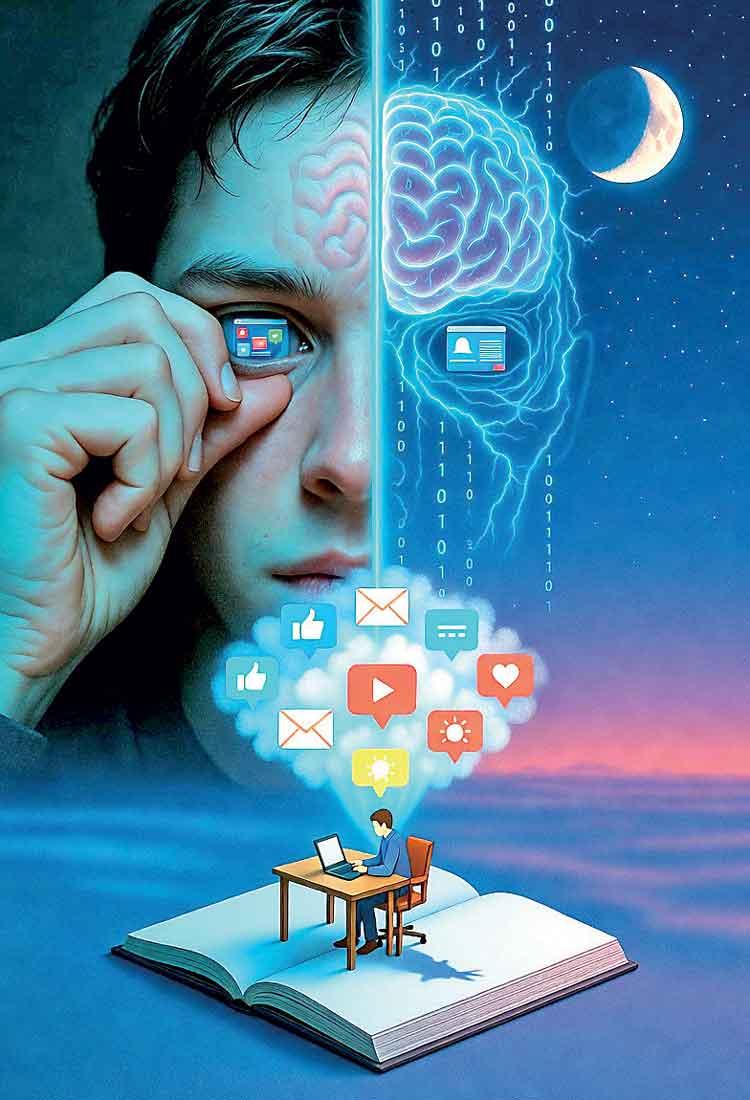

In today’s digital world, screens have become unavoidable. From smartphones and laptops to tablets and televisions, most people spend several hours a day looking at digital displays. While screens have transformed communication, education, and work, prolonged exposure has raised growing concerns about their impact on both eye health and brain function. Unlike short-term discomfort, long-term screen exposure can lead to subtle yet significant physiological changes that often go unnoticed until symptoms become persistent.

Impact on Eye Health

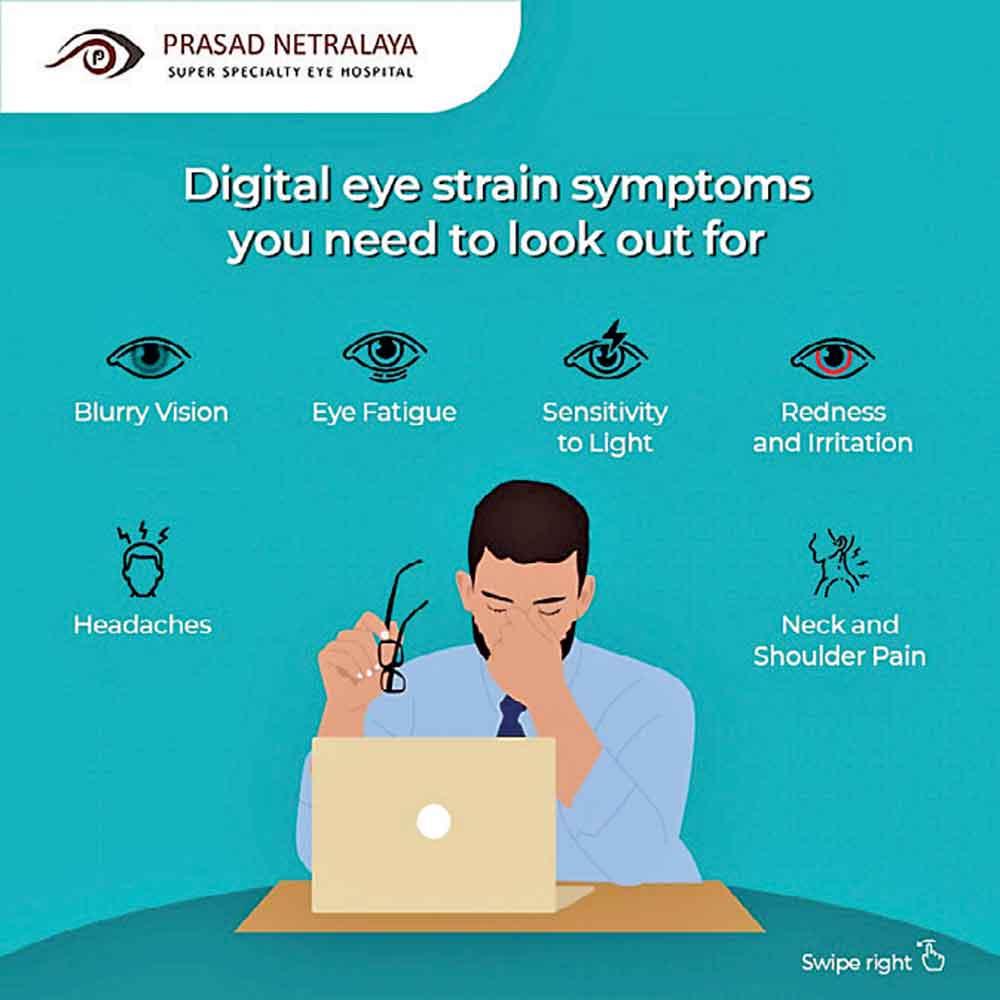

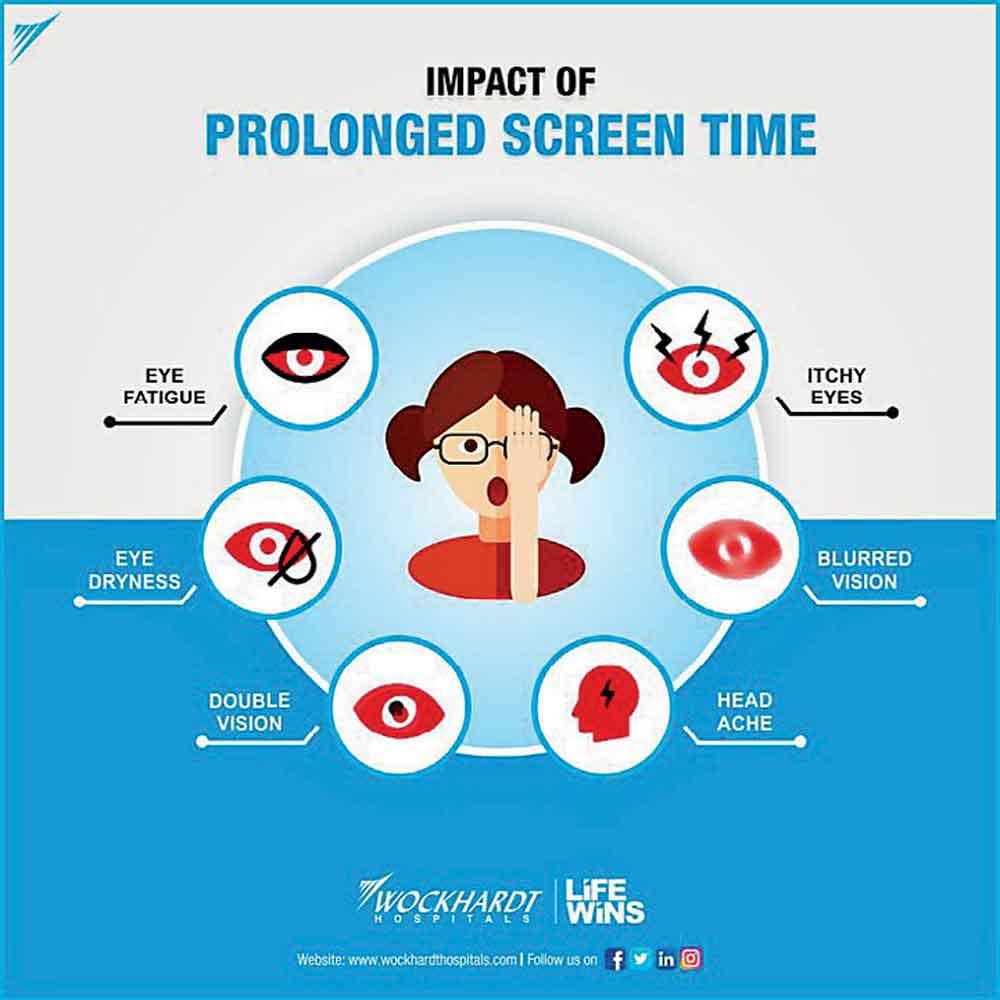

One of the most common consequences of prolonged screen use is digital eye strain, also known as computer vision syndrome. This condition develops not because screens are inherently harmful, but because the visual demands of digital displays differ from those of natural viewing. Screens require continuous focus, frequent refocusing, and sustained near vision, all of which place stress on the eye muscles.

A major contributing factor is reduced blinking. Under normal conditions, humans blink around 15–20 times per minute. During screen use, blink rates can drop by nearly half. Blinking is essential for spreading tears evenly across the surface of the eye, keeping it lubricated and protected. Reduced blinking leads to dry eyes, irritation, burning sensations, and redness. Over time, this can worsen tear film instability and contribute to chronic dry eye disease.

Long-term screen exposure also affects accommodation, the eye’s ability to focus on near and distant objects. Prolonged near work can strain the ciliary muscles responsible for lens adjustment. This may result in blurred vision, difficulty shifting focus, and headaches. In children and young adults, excessive near work has been associated with the progression of myopia (short-sightedness), a growing global public health concern.

Another issue is exposure to blue light, a high-energy visible light emitted by digital screens. While blue light plays a role in regulating circadian rhythms, excessive exposure especially in the evening can disrupt normal visual comfort. Blue light scatters more easily in the eye, reducing contrast and increasing glare, which contributes to eye fatigue. Although current evidence does not conclusively show that blue light from screens causes retinal damage, it does contribute to visual discomfort and sleep-related eye strain.

Effects on Brain Function

The brain is deeply involved in processing visual information, and prolonged screen exposure affects more than just the eyes. Continuous digital engagement keeps the brain in a state of heightened stimulation, which can alter cognitive function over time.

One key area affected is attention regulation. Rapid screen-based content, frequent notifications, and multitasking demand constant shifts in focus. This trains the brain to operate in short bursts of attention rather than sustained concentration. Over time, this may reduce the ability to focus deeply, process complex information, or engage in prolonged cognitive tasks without distraction.

Long-term screen exposure also impacts mental fatigue. Unlike physical tiredness, mental fatigue can develop even while sitting still. Continuous visual processing, decision-making, and information intake place a heavy load on the brain’s executive functions. This can lead to headaches, irritability, slowed thinking, and reduced productivity, even when sleep duration appears adequate.

Sleep and Circadian Disruption

One of the most well-documented effects of screen exposure is its influence on sleep and circadian rhythms. Blue light suppresses the secretion of melatonin, a hormone responsible for signaling the body to prepare for sleep. Evening screen use delays melatonin release, shifting the body’s internal clock. Chronic disruption of sleep patterns affects brain health in multiple ways. Poor sleep reduces memory consolidation, emotional regulation, and cognitive flexibility. Over time, insufficient or irregular sleep has been linked to increased risk of anxiety, depression, and neurocognitive decline. Importantly, these effects accumulate gradually, making them easy to overlook until they become persistent.

Neurological and Psychological Effects

Extended screen exposure may also influence the stress response system. Constant connectivity and information overload can activate the sympathetic nervous system, keeping the brain in a state of alertness rather than recovery. This prolonged activation contributes to mental exhaustion and may worsen stress-related conditions. There is also growing interest in how screen exposure affects neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to adapt and reorganize. While digital tools can enhance learning when used intentionally, excessive passive consumption may reduce engagement with deeper cognitive processes such as reflection, imagination, and critical thinking. In younger individuals, whose brains are still developing, excessive screen exposure may influence emotional regulation and impulse control. Although research is ongoing, moderation is increasingly emphasized as a protective strategy for long-term brain health.

Musculoskeletal and Visual-Brain Interaction

Eye and brain health are closely linked to posture and musculoskeletal alignment. Prolonged screen use often involves poor posture, such as forward head positioning and rounded shoulders. This can reduce blood flow and oxygen delivery to the brain, contributing to headaches and cognitive fatigue. Visual strain and neck tension often reinforce each other, creating a cycle of discomfort and reduced concentration.

Long-Term Consequences and Prevention

The long-term effects of excessive screen exposure are rarely dramatic but often cumulative. Chronic eye strain, sleep disruption, and cognitive fatigue can quietly reduce quality of life, work efficiency, and overall well-being. Importantly, these effects are not limited to professionals; students, children, and older adults are equally affected. Preventive strategies focus on reducing strain rather than eliminating screens. Regular visual breaks, proper lighting, appropriate screen distance, and conscious blinking can support eye health. Aligning screen use with natural circadian rhythms especially limiting exposure before sleep helps protect brain function.

Ultimately, screens are tools, not enemies. The key lies in understanding their physiological impact and using them in ways that respect the body’s biological limits. Protecting eye and brain health in the digital age requires awareness, balance, and intentional habits rather than avoidance.

Long-term screen exposure affects both eye and brain health through mechanisms that develop gradually and often silently. From visual strain and dry eyes to cognitive fatigue and sleep disruption, the effects are interconnected and cumulative. As digital devices continue to shape modern life, recognizing and addressing these impacts becomes essential for maintaining long-term neurological and visual well-being. In an era defined by screens, protecting health begins with understanding how deeply they influence the body.