Once upon a time, the documentary was journalism’s purest form. It was built on distance and discipline, not access or charm. Film-makers like Michael Moore and Molly Dineen treated the camera as a mirror for truth, not an accessory to fame. In Geri (1999), Director Dineen famously corrected Geri Halliwell’s assumption that she could edit out unfavourable moments. The message was clear, the subject did not own the story. That ethic held for decades. Even at the height of celebrity culture, documentaries carried moral weight. The Fog of War (2003) turned political power into a study of consequence. Fahrenheit 9/11(2004) weaponised facts against authority. The documentarian’s task was to observe, interrogate, and, at times, to discomfort. As Ken Burns once warned when criticising Michael Jordan’s involvement in The Last Dance (2020): “If you are there influencing the very fact of it getting made, it means certain aspects that you don’t necessarily want in aren’t going to be in.” Today, that independence has been quietly rewritten.

The New Truth Industry

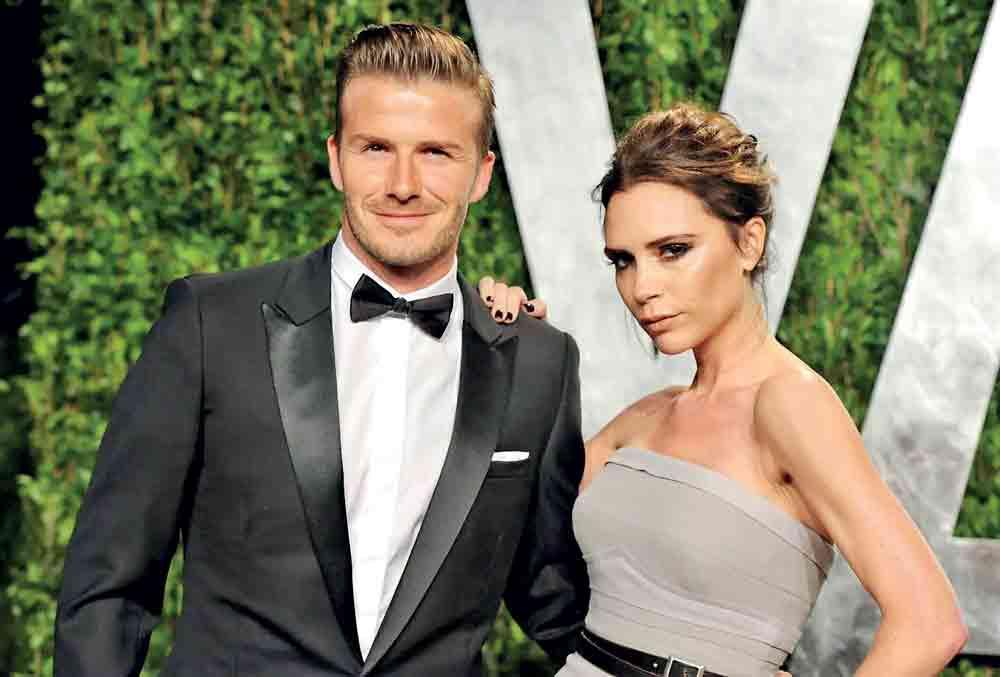

The documentary has been rebranded as both therapy and marketing. Almost every major celebrity now has, or soon will have, a streaming documentary. Beckham, Miss Americana, Pamela, A Love Story, and now Victoria Beckham (Netflix, 2025) show how fame has colonised a form once reserved for investigation. As Esquire observed earlier this year, “documentary is now as enamoured with celebrity as the most scoop-hungry paparazzo.” The new wave promises raw intimacy while offering controlled access. The camera lingers on domestic spaces, private confessions, and curated tears, all framed by immaculate lighting and legal sign-off. The result is an illusion of exposure: transparency without risk.

Image Control as Storytelling

In the modern celebrity documentary, authorship has shifted. The subject no longer grants access; they curate it. The film becomes a collaborative negotiation between publicist and platform. Netflix’s vice-president for original documentaries, Kate Townsend, describes the company’s approach as looking for “people who have relatable challenges and complexities in their everyday lives, as well as those special qualities that make them unique.” It is a revealing statement. What used to be a search for truth is now a search for relatability, empathy as entertainment. Fisher Stevens, director of Beckham, takes the shift further. “I don’t make them like a journalist,” he said. “I’m a humanist and a filmmaker.” That distinction defines this new era. The documentarian is no longer an investigator but a collaborator in a process of managed revelation.

The Beckham Case: Staged Vulnerability

Victoria Beckham’s new documentary, released this month, offers a textbook example. It reframes her story not as a celebrity’s rehabilitation but as a creative’s reappraisal.

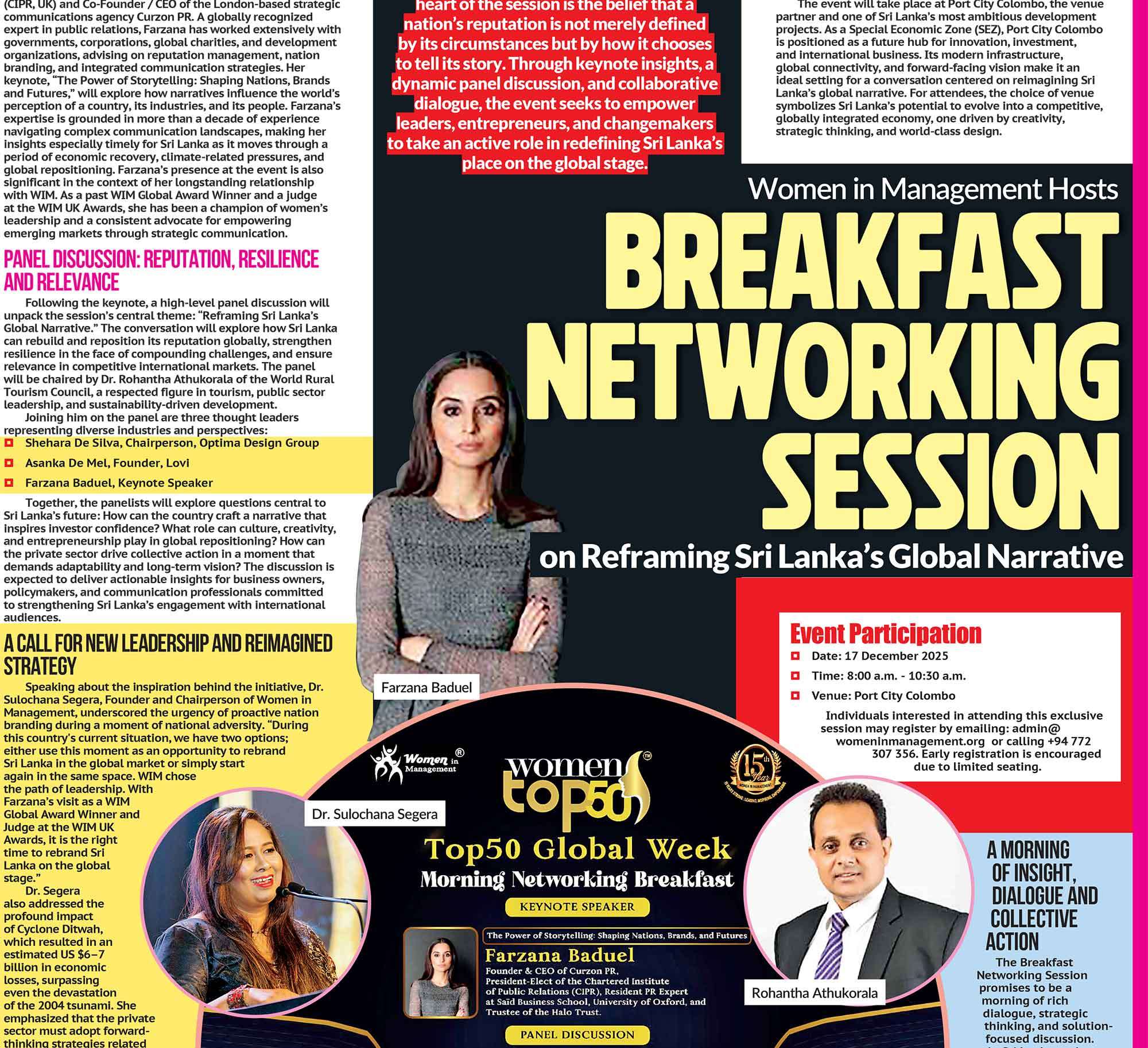

The series moves between her fashion house and her pop past, linking vulnerability with control. She acknowledges past criticisms, “I’d be lying if I said I was the best singer or dancer”, and revisits decades of tabloid mockery with humour and detachment. But beneath the humility lies precision. As Curzon PR’s CEO, Farzana Baduel, noted on BBC Radio’s The Media Show, “There’s a commercial play. There’s also a play in terms of legacy… she wants to set her story.” Farzana describes Beckham’s technique as “staged vulnerability.” By confronting old narratives, from “Victoria doesn’t smile” to rumours about her family, Beckham turns criticism into connection. “She has brought those vulnerabilities front and centre to then have a laugh about it, to make her more accessible,” Farzana said. “Her PRs have no doubt scoured what the repetitive narratives are that are negative, to confront, bring in, and then flip on its head… a really smart way of approaching it.” It is a masterclass in narrative inversion: take the accusation, reframe it, and sell it back as self-awareness. The authorised documentary has become the PR campaign of the streaming age. It merges authenticity with control, vulnerability with precision.

The Audience’s Complicity

These films succeed because they meet a cultural need. Viewers crave access, the illusion of intimacy with people they already know. What once looked like journalism now functions as a mirror for our own nostalgia. Lois Vossen, executive producer of PBS’s Independent Lens, has argued that “there is nothing wrong with non-fiction entertainment… but everything is now labelled ‘a documentary’.” That confusion is the heart of the matter. When the language of journalism is used to market entertainment, the viewer is invited to feel rather than to question. The new documentary no longer asks for trust; it assumes it. We watch not for revelation but for recognition, to see the human inside the brand, even when that humanity has been carefully scripted.

What’s at Stake

The rise of authorised access documentaries signals a cultural realignment. Where journalism once held power to account, public relations now shape the narrative of truth. The ethics of exposure have been replaced by the aesthetics of confession. This shift is not necessarily cynical. Many of these films do humanise their subjects and challenge the cruelty of past media coverage. But they also redefine truth as a managed performance. The line between documentation and promotion, between empathy and editing, grows thinner with every frame. Victoria Beckham’s series may succeed in softening her public image. It may even invite a fairer understanding of her long career. Yet it also represents something larger: a media ecosystem where access replaces accountability and self-narration becomes its own reward. When the subject holds the camera, the story might still move us, but it no longer belongs to the realm of journalistic truth.

This article has been republished with permission from Curzon PR (UK).

Online: https://curzonpr.com