Colombo Fort has never been ‘just’ a neighbourhood. Long before the city’s skyline was pierced by skyscrapers, and the area was dotted with five-star hotels, it was once the beating heart of the country’s maritime world. It was a nexus of trade, culture and power. Being wedged between the Indian Ocean and Beira Lake, its strategic location provided natural anchorage, and it was the gateway to the rest of the country.

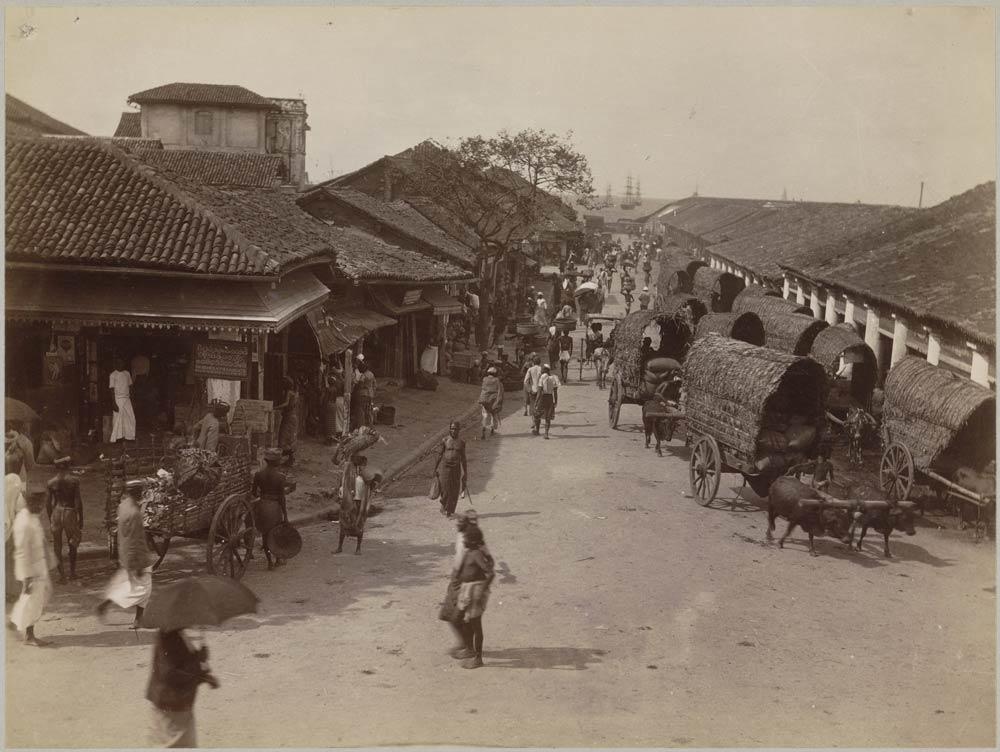

Ships carrying new ideas, people, and inventions would dock here; their hold heavy with ceramics, textiles, spices, dried fruits, jewellery, and other treasures. Weary sailors would arrive with salt in their hair to find respite on our warm shores; Arab merchants traded in perfumes and fine fabrics; Sinhalese vendors sold local produce and crafts; and Chettiar financiers (now known as Colombo Chettys) introduced the earliest systems of credit and banking.

Ships carrying new ideas, people, and inventions would dock here; their hold heavy with ceramics, textiles, spices, dried fruits, jewellery, and other treasures. Weary sailors would arrive with salt in their hair to find respite on our warm shores; Arab merchants traded in perfumes and fine fabrics; Sinhalese vendors sold local produce and crafts; and Chettiar financiers (now known as Colombo Chettys) introduced the earliest systems of credit and banking.

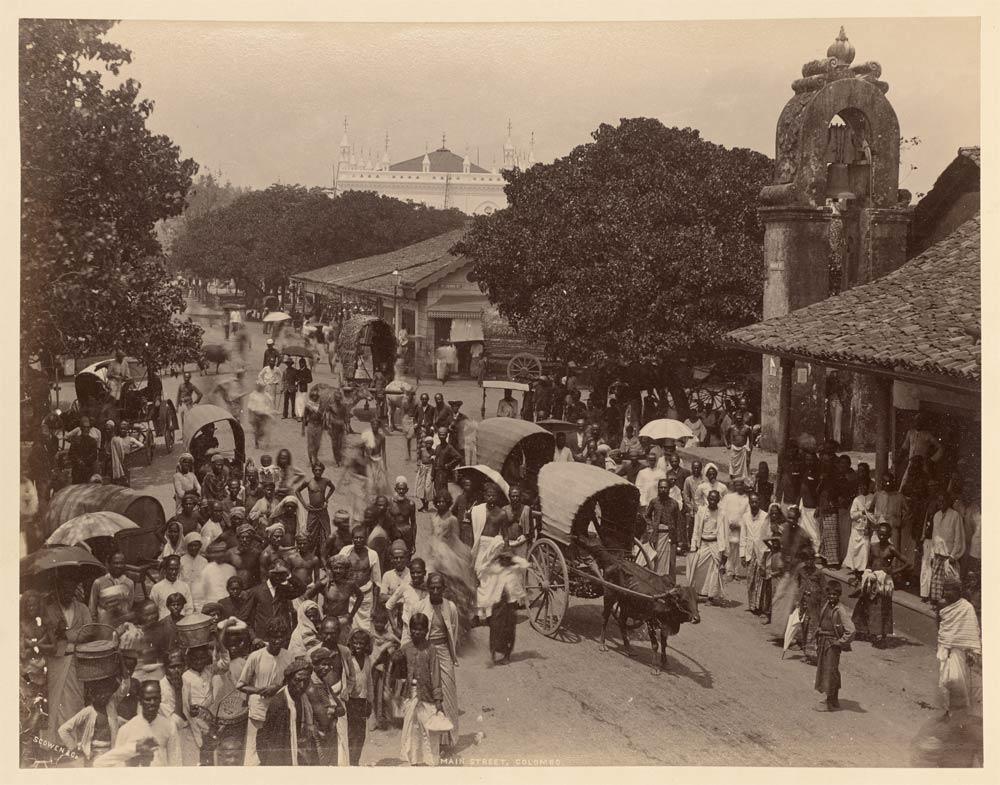

The streets pulsed with life, rang with the sound of goods being exchanged and the chatter of different tongues. Over the years, the Fort’s appearance and reputation may have changed –trying to find pieces of the actual fort itself is an almost Herculean task, however, its essence endures. Even though the shoreline has been pushed further away from Fort, the memory of its maritime past lingers in the air and whispers in the salty sea breeze.

A Fort in Flux

The Portuguese arrived in the early 16th century and built a small fort at their landing site. The initial structure was rather rudimentary, made with mud walls and ‘only’ had three bastions. However, over the course of their century-long rule, they developed the fort, transforming it from a mere fortress into a fortified town which boasted 14 bastions! During their reign, the Portuguese faced several attacks from local rulers, who tried on multiple instances to lay siege to the fort. Ultimately, Portuguese rule came to an end in 1656, largely because of Dutch interference.

The Dutch reinforced and redesigned the fort, digging a wide moat and connecting it to the crocodile-infested lake for added defense. The fort was impressive, and within its walls lay a self-contained city. There were administrative buildings, storehouses, mills, residential buildings and even stables for horses and elephants. The streets were lined by large shady trees and whitewashed Dutch-style villas with red-tiled roofs; a far cry from the commercial hub it is today.

Beyond the Ramparts

Beyond the Ramparts

During the Dutch era, the Fort’s surrounding areas of Pettah and Kompanna Veediya (formerly Slave Island) developed in tandem. Pettah, its Sinhala and Tamil names translate to ‘outside the fort, was where most of the local population resided during Portuguese rule. The Dutch reinforced this separation deliberately: Europeans inside the fort; locals and traders outside.

As they rebuilt the fort, they laid out the city into a dense grid of streets. A large road, Main Street, connected Fort with Pettah, while smaller trade-based streets flowed into the larger one. In fact, traces of their plan survive today: Sea Street for goldsmiths, Keyzer Street for cloth merchants, and Maliban and First Cross Streets for spice traders.

By the time the British captured Colombo in 1796, Pettah was already a thriving, cosmopolitan, commercial district with a mixed population. The British inherited this layout, but they demolished the fort’s walls and tightened the street grid, reshaping it into an open city of commerce. Unfortunately, only fragments of the original Dutch Fort, Delft Gate, Kayman’s Gate bell tower, and portions of the old ramparts, remain. They are scattered around Pettah and the port and have become quiet reminders of the Fort’s layered past.

A Cultural Tapestry

Colombo may not always wear its diversity out loud, but in Pettah, it speaks through every scent, sound and storefront. In 1803, Robert Percival, a British army officer, wrote ‘An Account of the Island of Ceylon.’ He was struck by how multicultural Colombo, especially Fort, was and claims that “there is no part in the world where so many languages are spoken, or which contains such a mixture of nations, manners, and religions.” Over two centuries later, his words still ring true. Through the years of trade and influx of people, Pettah thus became not just a trading area, but a living mosaic of faiths.

Whether it’s enjoying Jaffna-style curries at Hotel Mayura, which glow red with spices, or losing yourself in a fabric store that looks like Aladdin’s cave of wonders or snacking on some tart achauru washed down by a sweet, milky faluda, to walk through Pettah’s crowded, maze-like streets is to step into a piece of living history.

Restoration and Renewal

Change is no stranger to this part of Colombo. Over the past decade alone, the landscape of Slave Island and Pettah has shifted once again. The rows of weather-beaten, colourful old two-storey shop houses were demolished to make way for high-rises and new developments. Yet, amid the upheaval, a quiet revival is now taking shape. Independent cafés, creative spaces, and bars are moving into restored buildings, breathing new life into the city’s colonial bones.

New voices are reclaiming old spaces. Entrepreneurs like Nishi Wariyapola and Mahesh Alkegama, founders of Radicle Specialty Coffee, have transformed a once-forgotten building on Chatham Street into a light-filled café and art gallery. This duo has been steadily redefining Colombo’s café culture, and their new venture might be their greatest one yet. A short walk away, the Old Fort Café, a laid-back restaurant and the restored New Colonial Bar feel almost unchanged by time. Finally, there’s the new kid on the block, Kampong. This speakeasy-esque bar is brought to you by the same team that opened GINI. Here, each cocktail channels an element of bygone Colombo, a mix of freshness and nostalgia that perfectly captures the city’s evolving spirit.

A Living Legacy

Still, not everything has changed. Some institutions have withstood the test of time, their doors open for generations. Hotel Nippon, which has served diners since the late 19th century, continues to carry the charm of old Ceylon (and oh, those delicious mutton rolls!). Family-run businesses, like the antique store Noor Hamees, line the narrow bustling streets of Pettah and pass their trade secrets from parent to child, anchoring the area in memory even as it modernizes.

Perhaps most inspiring is how Pettah’s spirit continues to spark creativity in young Sri Lankans. The district’s energy and resilience have become a muse for a new wave of entrepreneurs. I’ve seen clothing brands, like Ammiro, or glitzy restaurants in London like Hoppers and Kolamba, draw inspiration from the textures, colours, smells and flavours of these storied streets to craft something distinctly modern yet rooted in heritage.

In this way, Fort and its surroundings are still alive, constantly rebuilding, reinventing, and reminding us that history is never truly in the past.