Of all the instruments of war and pageantry at the command of the Sinhalese kings, there was none so formidable, so revered, nor so symbolically potent as the elephant.

Through centuries of dynastic rise and fall; from the plains of Anuradhapura to the craggy citadels of Sitawaka, the war elephant loomed not only as a physical force but as an ideological creature, employed in the service of statecraft, ritual, and conquest. It is within this dual nature [both beast and emblem] that the elephant must be understood not merely as a military asset, but as an epistemic signifier of sovereignty and moral order. The role of elephants in Sri Lanka’s martial history is not incidental, nor confined to anecdote. It is inscribed into the very fabric of the island’s political and religious consciousness. From early references in the Mahāvamsa to the complex taxonomies of court regiments under Parakramabahu I, the elephant emerges as an ever-present companion to the figure of the king, a moving monument, a carrier of banners and relics, a breaker of gates and lines, and ultimately a mirror of power itself.

In Chronicle and Combat: The Earliest Mentions

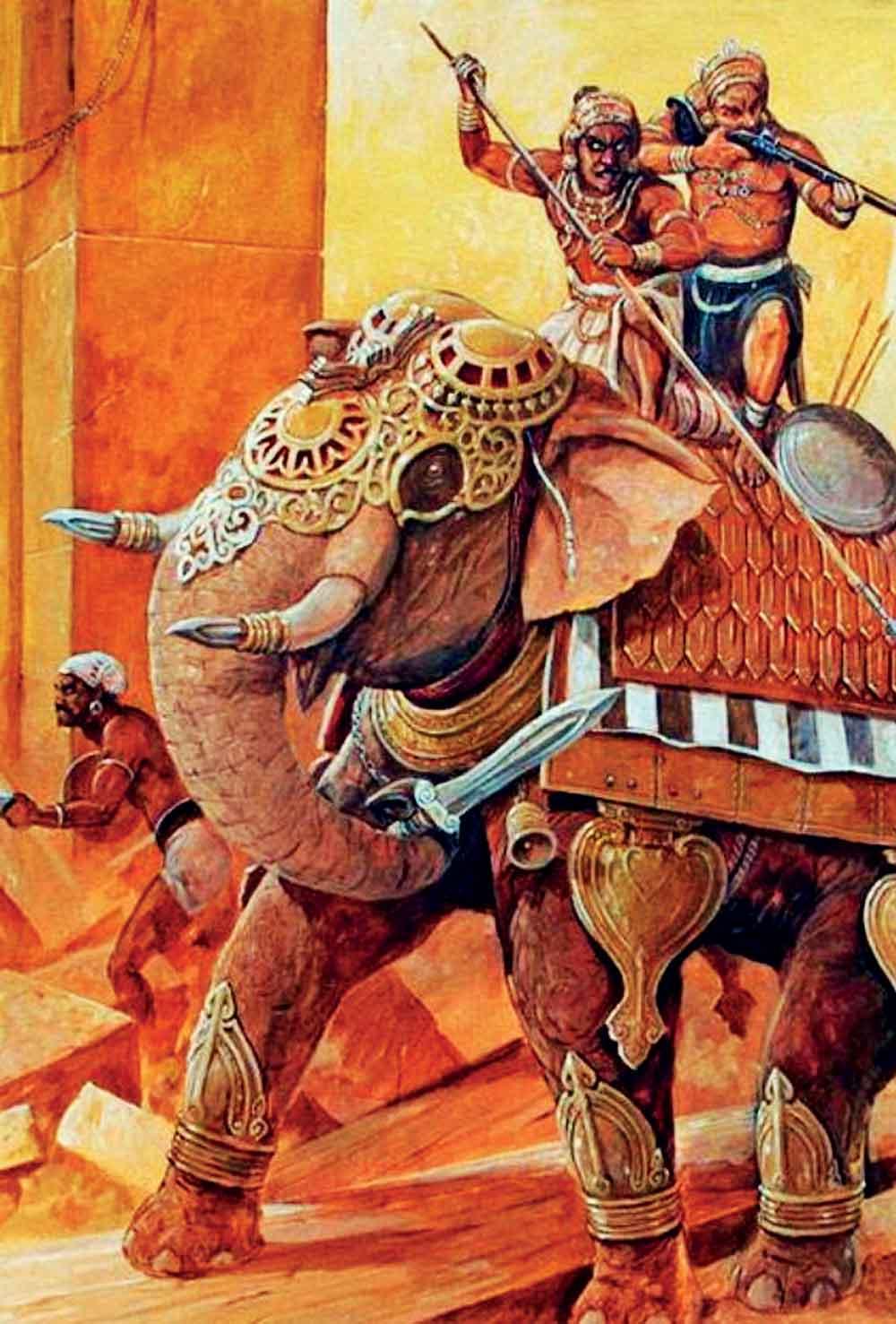

The Mahāvamsa first records the elephant’s martial prominence in the celebrated tale of Kandula, the steed of King Dutugemunu. In Book XXV (vv. 12–22), Kandula is said to have been born on the same day as the prince and trained under special care at the royal stables. When the time came for the climactic confrontation with Elara, it was Kandula who carried the king into the southern gate of Anuradhapura. The text tells us that the elephant shattered the enemy lines, unhorsed the rival monarch, and stood at his master’s side during the ensuing duel. It is no idle embellishment. The chronicles; deeply invested in linking political authority to moral legitimacy, cast the elephant as an agent of righteous restoration. The duel at the gate is less a military tactic than a theatre of cosmic justice, with Kandula symbolising the alignment of natural force with Dharmic kingship.

The text tells us that the elephant shattered the enemy lines, unhorsed the rival monarch, and stood at his master’s side during the ensuing duel.

The Institutionalisation of the Elephant

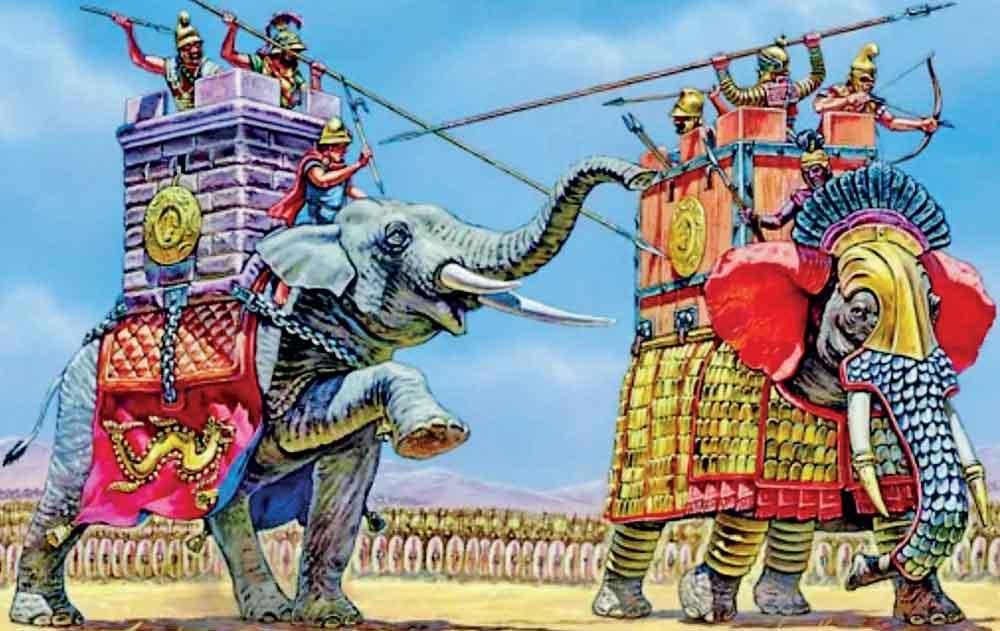

The transition from symbolic actor to formalised military unit occurred over the long centuries of the Anuradhapura and early Polonnaruwa periods. In Book XXXI of the Cūlavamsa, the campaigns of Parakramabahu I are described in detail, with elephants leading columns through jungle and river, battering down ramparts and carrying siege engineers in tower-like howdahs. These were not rogue beasts but trained, catalogued, and provisioned soldiers of the state. Indeed, the administrative machinery surrounding elephants was both intricate and enduring. As recorded in the Epigraphia Zeylanica (Vol. II), royal grants from the 12th century delineate elephant forests (hatthivanaya), stables (hatthisālā), and officials such as the hatthika-nāyaka and hatthidamana (keeper-trainers). These titles correspond to similar structures found in the Chola and Kalinga courts of the subcontinent, underscoring the elephant’s regional military importance and the shared Indo-Aryan martial cosmology in which mastery over elephants conferred political gravitas.

Ritual, Relics, and the Aesthetic of Majesty

The use of elephants extended far beyond the battlefield. As described in Book XLIV of the Cūlavamsa King Parakramabahu II employed elephants to carry the Tooth Relic through the capital during major processions, a tradition still echoed in the Esala Perahera of Kandy. The elephant thus came to signify ritual continuity, bearing upon its back not a general, but the very legitimacy of the state, now embodied in sacred tooth or scripture. In courtly art and temple sculpture, elephants flank entrances and staircases; their forms are repeated in moonstones and friezes. The presence of the elephant in these liminal spaces; thresholds of temples and palaces, symbolises protection, transition, and grandeur. That they appear in such abundance suggests not mere reverence but architectural theology: the elephant as sentinel of both worldly and spiritual power.

Terrain and Tactics: From Plains to Hill Forts

With the post-Chola shift of royal power to Dambadeniya, and subsequently to Yapahuwa and Gampola, elephants underwent a modification of purpose. In the narrower ravines and elevated escarpments of the hill country, elephants lost their capacity to charge in ranks. Yet they remained present, now recontextualised as emblems of sovereignty rather than engines of war. It was during this period that the elephant became increasingly associated with spectacle. The Tooth Relic processions, the coronation marches, and the great temple consecrations all required the presence of tusked giants adorned in caparisons, bearing parasols and banners. Their aesthetic was deeply political: a dramatization of lineage, legitimacy, and cosmic order. Nonetheless, they retained some battlefield function. Manuscripts from the era of Parakramabahu IV mention units of elephant cavalry (hatthī-senāpati) stationed at Mātale and Kurunegala, employed in skirmishes against both internal rebels and maritime raiders.

The Gunpowder Shift: Kotte and Sitawaka

The advent of European firearms in the 16th century brought with it a crisis in elephant warfare. The Portuguese, with their muskets and cannon, introduced a technological asymmetry that nullified the shock value of the elephant. The Rajavaliya recounts several engagements in which elephants, upon hearing the roar of cannon, panicked and trampled friendly lines. Mahouts were issued daggers with which to kill their mounts in such instances—a tragic and brutal testament to both the animal’s tactical vulnerability and its perceived indispensability. Yet even in this age of obsolescence, elephants retained ceremonial primacy. In Kotte, Sitawaka, and later in Kandy, they continued to occupy a central role in processions and temple rites, a lingering presence from an older world, whose decline did not diminish its splendour but rather cast it in nostalgic relief.

Comparative Notes: Beyond Lanka

A comparative glance eastward and northward reveals that Sri Lanka’s use of elephants shares affinities with broader South Asian traditions but also displays distinctive features. In the Mauryan Empire, as per Megasthenes, elephant corps were deployed in ranks of hundreds, used to intimidate and overwhelm. In South India, Chola inscriptions speak of elephant raids into Sri Lanka itself. Yet the Lankan pattern differs in its sacral investment—elephants are more fully woven into the religious and symbolic fabric of polity than in most continental analogues.

They were not simply chariots of war, but repositories of ritual, companions of relics, and symbols of the dhammarāja ideal. The Sinhala king did not merely ride the elephant, rather he absorbed its gravitas into the semiotics of rule.

Conclusion: The Long Shadow of the Elephant

To trace the elephant through the history of Sri Lanka is to trace the arc of kingship itself. From kinetic conquest to ceremonial centrality, from battlefield shock to relic-bearing dignity, elephants were not just instruments of force but bearers of narrative: of sovereignty claimed, contested, and sanctified. Their bones lie beneath the earth, their names fade in the chronicles, but their memory endures, in pageant, in sculpture, in chant. In the trunk that once bore the king, the relic, and the sword, we find a cipher of the island’s long, luminous, and layered past… a beast not of burden, but of meaning.