In the mirror of memory, childhood should reflect innocence. But on a small tear-shaped island in the Indian Ocean, that reflection fractures. The same country. The same years. Two vastly different childhoods, divided not by oceans, but by the accident of birth, by language, ethnicity, and history. Sri Lanka. One island. One anthem. But not one reality.

Colombo, the Capital of Comfort

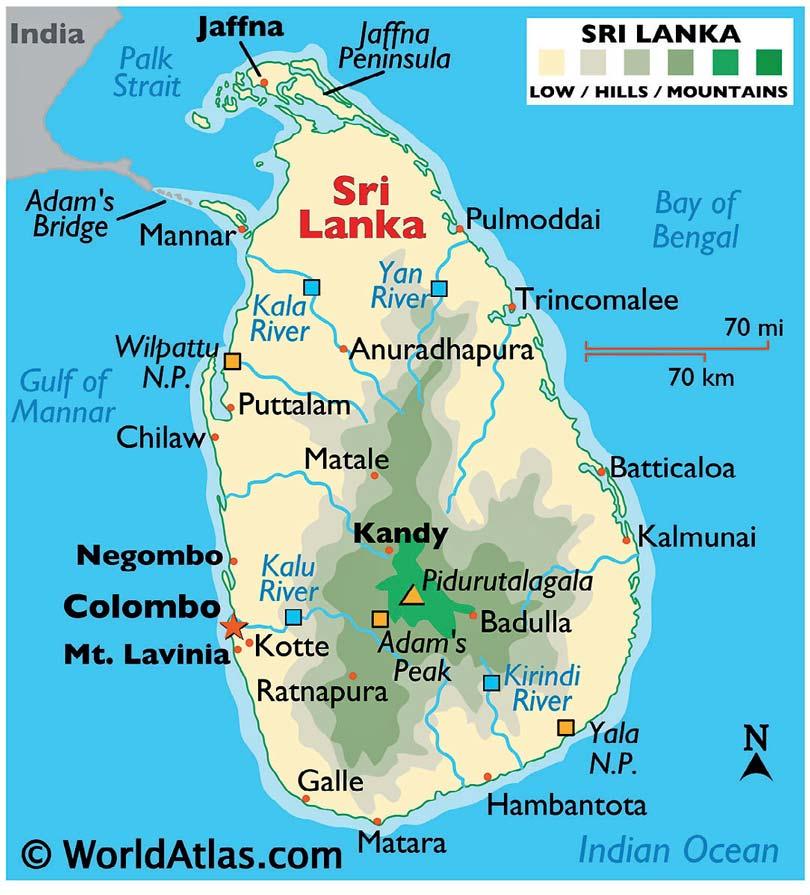

Ananya grew up in Colombo 07, one of the capital’s most affluent enclaves. Hers was a life of privilege woven seamlessly into the ordinary. A beautiful home with a sprawling garden, a Labrador named Max, a family driver, a fleet of household staff, a weekly routine of piano lessons on Wednesdays, tennis on Thursdays, and ballet on Saturdays. Her school uniform was always starched, her birthday parties themed and well-attended. The war, though ever-present in the background, was mostly an abstraction, a distant hum on the evening news between cricket scores and weather forecasts. She knew it was happening. She even knew people who had lost someone. But her world wasn’t shaped by fear. “Batticaloa? Where’s that?” she’d ask, barely glancing at the TV, more concerned about whether the macaroni and cheese was too cold. There were no frequent air raids in Cinnamon Gardens. No emergency drills. No bunkers. Her memories of those years are framed with Barbie dolls, sleepovers, class trips, pool parties, and a quiet, unspoken belief that everything she had, electricity, clean water, safety, and education, was normal. A birthright. She was Sinhalese, and she never had to question what that meant in practical terms. Her biggest fear was failing a maths test. Her biggest trauma was missing an overseas holiday because of a visa delay. When Colombo was placed under curfew, it wasn’t fear she remembers; it was adventure. She recalls sneaking into nightclubs with her friends, the thrill of being stopped at army checkpoints, only to casually flash her ID, a pirith noola around her wrist, or drop the name of someone in the military or government. The war was an inconvenience, yes, but never a direct threat. That was her war. One viewed from behind the tinted windows of a BMW. A war she could choose to tune out.

Batticaloa, the Battleground of Broken Dreams

But on the other side of the island, in Batticaloa, Kavitha was learning how to survive. Hers was not a childhood of extra-curriculars or birthday cakes; in fact, she cannot recall ever celebrating a birthday, not until years later, after her family relocated to Europe. Her earliest memories were punctuated by curfews that weren’t thrilling, but terrifying. She remembers sleeping in sarongs under wooden tables when shellfire came too close. She remembers her mother always keeping a bag packed by the door; the “run bag,” they called it. In case they had to flee. Again. The enemies shifted: sometimes soldiers, sometimes Tigers, often both. One in Sinhala. One in Tamil. Neither safe. They lived in fear of recruitment by the LTTE. Of checkpoints that didn’t ask questions. Of men with guns who saw boys as cannon fodder. Kavitha recalls the night LTTE cadres came to her neighbourhood. She and her brothers ran barefoot through back alleys, hiding in a camp until dawn. She remembers her cousin, Sandeep, being shot in front of her, a name that still makes her chest tighten. She was twelve. She didn’t cry. There was no time for tears. School was not a given. It was a luxury. One that could be snatched away any morning by gunfire, or by the need to flee to a displacement camp. When aid workers handed out biscuits and colouring books, she stared at the crayons, not knowing what to draw. What colour was war?

Every morning, her mother would wipe the red pottu from her forehead before she left the house. The jasmine flowers in her hair were removed. “Too Tamil,” her mother would whisper. “Don’t give them a reason.” Fear was not an event in Kavitha’s life. It was a setting. It was the air she breathed.

The Lie of One Nation

For years, the narrative was that Sri Lanka was one country; united under one flag, one identity, one fight. But that story was never quite true. In reality, Sri Lanka was two nations trapped within a single name. In one version, curfews were a mild inconvenience. In the other, they were a matter of life or death. In one version, a girl wore her pirith noola with pride, flashing it at checkpoints as a silent badge of Buddhist identity. In the other, a girl was stripped of her cultural markers before stepping outside. The red pottu wiped clean. The jasmine removed. Her identity, erased for safety. In one household, parents worried about grades and boyfriends. In the other, they worried whether their children would live to see the end of the week. The divide was not just geographic; it was social, linguistic, religious, political. It was built on systems, history, and the convenient ability of one group to look away. The war was long, bloody, and brutal. But perhaps its cruellest legacy is this: two children, born on the same island, under the same sky, speaking different tongues, living realities so distant they may as well have been born on opposite ends of the earth.

When the War Ended, the Divide Did Not

The guns fell silent in May 2009. But peace is not merely the absence of bullets. Peace requires justice, dignity, recognition, and memory. Without those, silence becomes another kind of violence. Today, both women are adults. Ananya now runs a luxury hospitality company in Colombo. Her life is one of business-class travel, brand launches, rooftop cocktails. Kavitha lives in Kattankudy, raising two children and working for a grassroots women’s initiative. She is still rebuilding a life that never quite had a chance to begin. They met at a Women’s Day panel discussion. Both were invited to speak; Ananya as a successful entrepreneur, Kavitha as a community voice. They smiled politely, posed for a photo, thanked each other on stage. After the event, Ananya approached Kavitha, hoping to connect. She spoke about how “the war affected all of us,” referencing the economic toll, the fear during the Colombo suicide bombings, and friends-of-friends who had died in attacks. Kavitha nodded, but when she spoke of her own war, the conversation changed. She spoke of hiding with her siblings, of recruitment drives, of the camps, of hunger, and the constant, gnawing fear. She spoke of watching her cousin’s body go limp in her arms. She spoke of what it meant to have a childhood that was never allowed to be a childhood. Ananya went quiet. She felt something rise in her, not guilt, exactly, but shame, and the sharp sting of realisation. The phrase she had casually thrown out, “we all suffered,” now felt hollow, even offensive. Yes, the entire country had suffered in some way. There were bombs in Colombo. Families were shattered. Lives were lost. But there had never been parity of experience. Ananya had known fear, but not like this. She had known loss, but not this kind of loss. She had grown up with memories; soft, scented ones. Kavitha had grown up with scars.

Ananya had known Avurudu in the hills, long weekends in Bentota, school holidays overseas, birthday parties at five-star hotels. She had known coexistence; her childhood friends were Sinhalese, Tamil, Burgher, Muslim. Kavitha had known silence. She had known what it meant to be Tamil, Catholic, and from the East; to live in the crosshairs. In that moment, Ananya understood the truth: they had not lived through the same war. They had lived on the same island, but not in the same world.

The Cost of Silence

The Sri Lankan war did not just end lives; it divided the living. And what remains today is a nation that speaks of unity but often fails to listen to each other’s truths. Until we can sit at the same table and truly listen, without defence, without dilution, reconciliation will remain a hollow word. A placeholder. A performance. Because peace is not built with silence. It is built with stories. With memory. With discomfort. It is built by telling the truths no one wants to hear, especially those we’ve spent years pretending didn’t matter.

This article was inspired by a conversation with a young millennial mother of Sri Lankan Tamil Catholic origin from the Eastern Province, now living and working in the UK. While not a personal memoir, it seeks to reflect the parallel realities experienced by many across the island.