Some of you may be wondering why this week’s column shifts from my ongoing series on Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) to something seemingly distant, Sri Lanka’s history curriculum.

But I believe it’s not distant at all. Whether we’re talking about FGM, the Chemmani mass graves, the erasure of women's voices, the genocide in Gaza, or the wars our textbooks forget to mention, these are all issues born from selective memory, silenced truths, and uncomfortable histories. They stem from what we choose to teach, and more dangerously, what we choose to omit. If a nation is raised without knowing the violence women have faced, the suffering of minorities, or the deeper roots of global injustice, we are not educating, we are blindfolding. This is why I write. Because justice, human rights, and truth are not isolated topics. They are threads of the same torn fabric. And I believe we must write and speaking until the threads are stitched together with honesty.

History Education in Sri Lanka

Behind closed doors, a debate rages over whether history should be a mandatory subject for all school students in Sri Lanka. The Prime Minister’s recent clarification to the rumors, confirmed that history and aesthetics remain mandatory only within the Humanities and Social Sciences streams, but become elective for others. This too surely has sparked mixed reactions.

Some have exhaled in relief, taking this as a sign that history isn’t being removed from the curriculum entirely. Others, like me, remain wary, knowing full well how subjects are softened into silence. You don’t eliminate history in one go. You marginalize it. First, you tuck it into a stream. Then you make it optional. Then you quietly phase it out. That’s how erasure works. But even if we were to accept the government’s explanation, it doesn’t address the core problem. Because this crisis didn’t begin with the elective status. The real problem is older, deeper, and more damaging.

History in Schools Is Already Broken

For decades, history has been taught in Sri Lankan schools as little more than a rote memorization exercise. Names of kings, dates of reigns, irrigation tanks built, battles fought, a parade of facts with no soul, no context, no space for interpretation or connection. This isn’t education. It’s indoctrination through tedium. But more dangerous than how it is taught is what is being taught. The official school curriculum often leans on the Mahāvaṃsa, a Buddhist chronicle, as a historical source. Religious text is not the same as historical evidence. When the stories of ancient Sinhala kings are passed off as fact with Tamil kings labelled as foreign invaders and battles framed as divine missions to protect Buddhism, what are we really doing?

We are scripting identity. We are telling young children that some communities belong more than others. We are quietly preparing the soil for hate to grow.

Competing Textbooks, Competing Truths

Let’s pause here. In Sri Lanka today, the Sinhala and Tamil versions of the same textbook tell contradictory stories.

- In the Sinhala version, King Dutugemunu is a heroic unifier who defeated a Tamil invader to preserve Buddhism.

- In the Tamil version, King Elara is described as a just and respected ruler.

Both cannot be true. Or rather, both can be true from different perspectives. But our curriculum doesn’t encourage discussion, critical thinking, or historical analysis. It enforces belief. Pick a side. Swallow it whole. This isn’t just an educational flaw. It’s a political weapon.

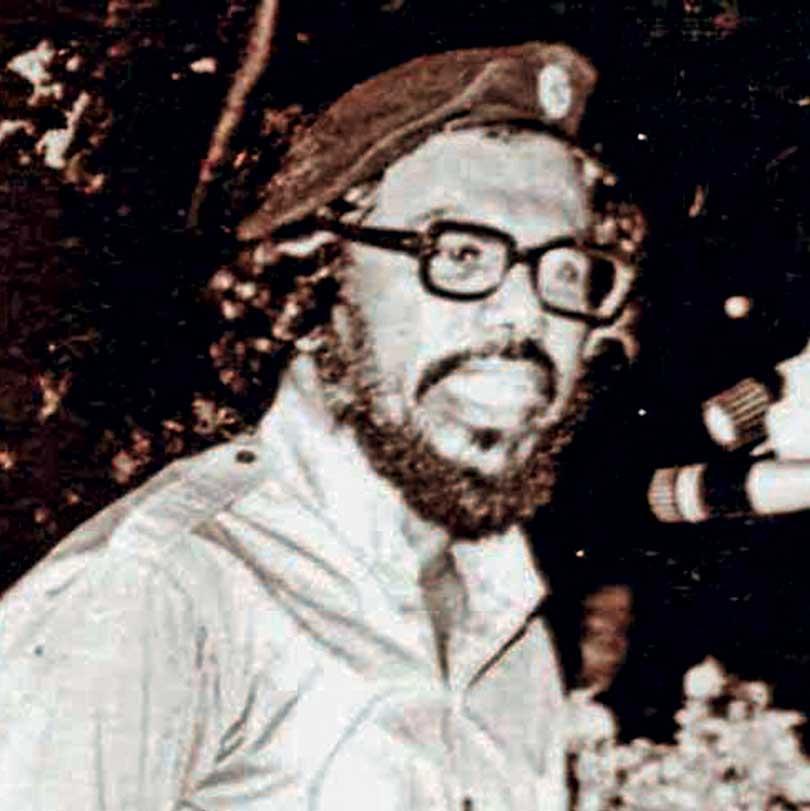

Selective Amnesia

Ask the average Sri Lankan student today about the JVP uprisings, the anti-Tamil pogroms of Black July, the disappearances in the North and East, the mass graves of Chemmani, or the Sinhala-only policies that triggered decades of ethnic tension. Chances are, they’ll either say they don’t know or that it wasn’t covered in class. How is this possible? Because the syllabus has carefully sidestepped the most painful, recent, and politically controversial chapters of our national story. It’s far easier to talk about tanks and kings from 2000 years ago than to confront the brutal truths of the past 50. But truth delayed is truth denied. Every time we skip these lessons in school, we raise another generation incapable of understanding why Sri Lanka remains fractured. We tell our children: forget the wounds; they’ll heal themselves. But they never do.

The Silence at Home

And where school stops, the home often doesn’t take over. In many households, talking about events like Chemmani, Black July, or even Palestine, is brushed off as “too controversial” or “politically sensitive.” But when truth becomes taboo, ignorance becomes culture. During my time teaching history at a private school, I taught a class of mostly Muslim female students. The curriculum was dry and outdated, mostly focusing on ancient rulers, tanks, and relics. I tried to breathe life into it, to show how history connects to today. Once, we discussed the poem "Big Match 1983" by Yasmine Gooneratne in the literature class, a powerful piece that spoke about the Sri Lankan Civil War. And not long after, it was quietly removed from the literature syllabus for being "too controversial." Where is the line between education and censorship? This is not just about a subject. It’s about our right to remember.

What’s at Stake If History Is Marginalized

The argument for history as a mandatory subject isn't sentimental, it's strategic. No country can move forward unless its citizens understand where they come from. This is especially true in post-conflict nations like Sri Lanka. Look at Germany, where Holocaust education is mandatory. Rwanda, where schools teach about the genocide and reconciliation process. South Africa, where apartheid is studied with brutal honesty. These countries understood something vital: you can’t bury your trauma under a syllabus. You have to confront it, name it, and teach it, so it never happens again.

The Syllabus Itself Needs a Revolution

Let’s be clear. The solution isn’t just making history mandatory up to O/Ls. It’s about completely redesigning the curriculum.

We need:

Honest, inclusive accounts of Sri Lanka’s post-independence history

Lessons on colonialism, the plantation economy, and caste

Analysis of the Civil War from multiple perspectives

Case studies of global conflicts like Palestine, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Ukraine

Feminist histories, labour movements, and resistance narratives

Critical engagement with sources, biases, and historical interpretation

This kind of history doesn’t produce memorizers. It produces thinkers.

Why Reform Feels Impossible

Many argue that history can’t be taught honestly because it’s too political, too risky. That if we include certain truths, we might offend some communities. That opposing narratives will create division. But the absence of truth is already dividing us. When you teach only one version of a story, you erase someone else’s. That silence becomes a wound. Curriculum reform is not impossible. It’s uncomfortable. But discomfort is the first step to healing. And if we’re serious about reconciliation, we need to stop pretending that avoidance is peace.

Teaching History to All Streams

Making history elective after Grade 9 is like saying, “You only need to know your country’s story if you’re studying humanities.” But that’s absurd. Future doctors, engineers, IT professionals, entrepreneurs; they all live, work, vote, and influence society. They need to understand race, religion, class, conflict, and identity just as much as any social science student. This isn’t a debate about humanities vs. science. It’s about creating citizens, not just workers.

The Poll That Said It All

The Link Between Historical Ignorance and Modern Injustice

You asked why some people don’t know about Chemmani. Why Nakba isn’t taught alongside the Holocaust. Why women’s bodies are still controlled under cultural practices rooted in distorted histories. Because when you fail to teach a people their past, they become easier to control. They ask fewer questions. They swallow what they’re told. They mistake silence for peace and forget that justice has a memory. That’s why even FGM, as I’ve written before, persists. Because in many cultures it has been justified as "tradition," its origins never questioned, its history never interrogated. Education: real, unfiltered, and critical education, is the antidote.

What Must Be Done Now

This Is Bigger Than a Subject