Arvind Subramanian

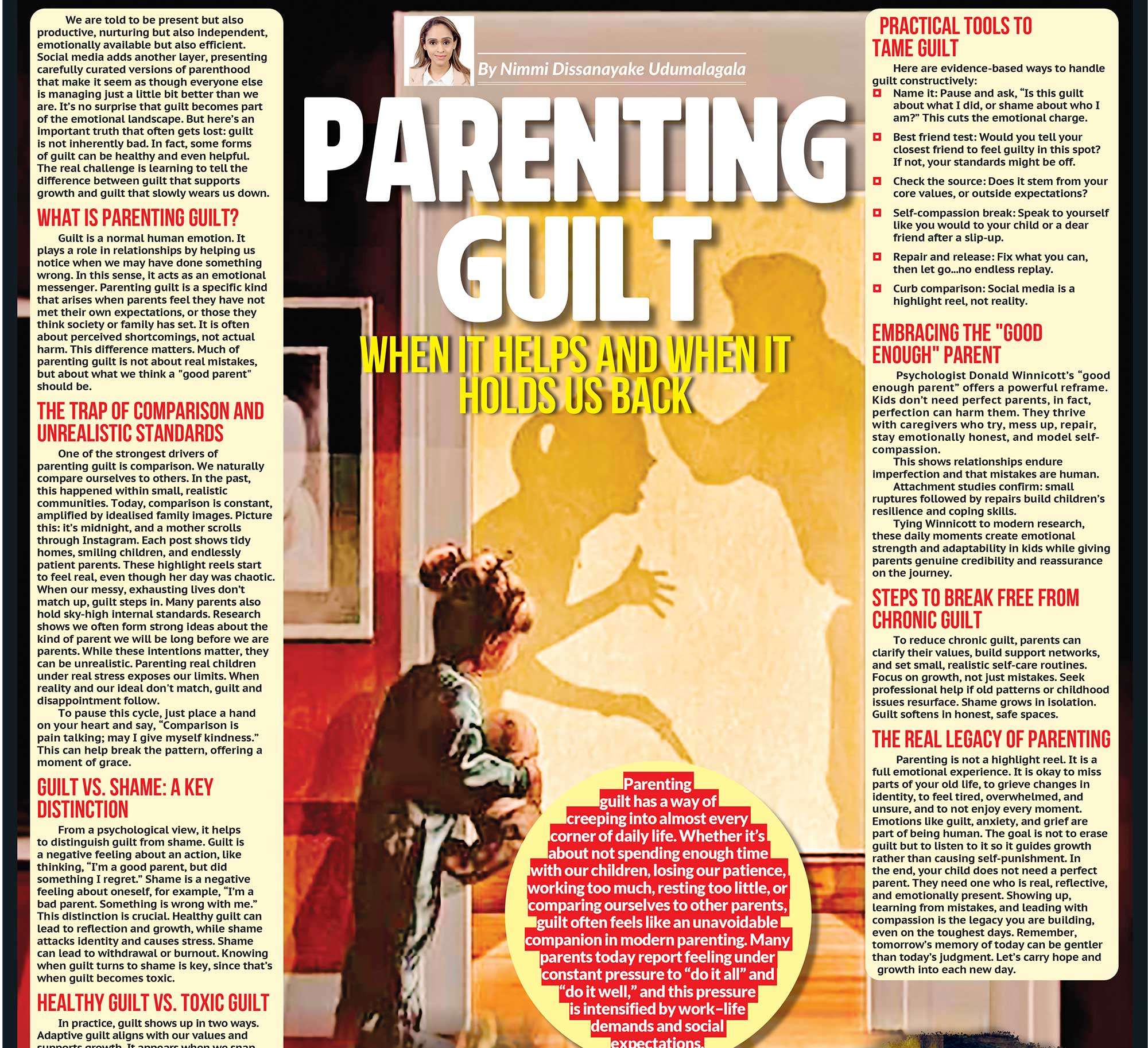

I had the pleasure of attending a fascinating discussion on “Lessons for Sri Lanka’s Growth” with Arvind Subramanian, former Chief Economic Advisor to the Government of India. Named among Foreign Policy’s Top 100 Global Thinkers, Arvind has also worked at the IMF and taught at Harvard, Brown, and Johns Hopkins universities. The event, hosted by the co-founders of The Examiner; Daniel and Mimi Alphonsus, drew a packed audience at Colombo’s Orient Club.

Comparing Sri Lanka’s economic trajectory with that of its neighbours, most directly India, Arvind drew on insights from his new book with Devesh Kapur, ‘A Sixth of Humanity,’ which he describes as “Independent India’s Development Odyssey.” His talk examined why Sri Lanka’s democracy has not been able to achieve the same economic outcomes as Indian democracy. Notably, he had already questioned Sri Lanka’s economic fate in 2019 in his article “Is Sri Lanka the Next Argentina?”, in which he asked whether the country would, like Argentina, remain trapped in a cycle of debt, crisis, and stagnation.

Strikingly, in 1960, Sri Lanka was far ahead of its South Asian peers in terms of human capital, as reflected in indicators such as literacy, infant mortality, and poverty reduction. Yet Sri Lanka’s economic growth, curiously, failed to keep pace with these human development gains. India, by contrast, lagged behind during that period but has since markedly improved its human capital, driven by sustained economic expansion, effectively the inverse of Sri Lanka’s economic course.

Another perplexing factor to him was that Sri Lanka received higher foreign direct investment inflows (relative to GDP) than the South Asian average until 2007 yet continued to underperform economically. What he also found equally confounding was Sri Lanka’s turn toward deglobalization at a time when the world was rapidly integrating, between 1990 and 2010. While many developing countries, including India, raised their standards of living during this era, Sri Lanka’s performance deteriorated. Echoing President Obama’s oft-cited foreign policy maxim, “Don’t do stupid sh*t,” Arvind argued that successful developing economies refrained from self-defeating policies, such as excessive state control, and, as a result, reaped the gains.

Reflecting on the missteps in Sri Lanka’s economic course, Subramanian pointed to the country’s heavy reliance on foreign capital, particularly foreign-currency debt, for example, by the billions borrowed from China. While India has not entered an IMF program since the early 1990s, Sri Lanka has repeatedly returned for support. Subramanian asserted that these structural, institutional, and fiscal contrasts have advantaged India while constraining Sri Lanka. His hope is that, twenty years from now, the chart tracking Sri Lanka’s IMF engagements will finally register zero, suggesting an end to this cycle that has long stymied development.

Another factor he highlighted is the declining tax-to-GDP ratio, signalling a deeper dysfunction in the relationship between society and governance. Addressing this requires getting to the heart of these underlying challenge, such as public distrust, and designing mechanisms to prevent their recurrence.

Central to his recommendations for Sri Lanka was the imperative not to forget the past, even as short-term reforms take hold. Sri Lanka’s crisis, he noted, was exceptionally severe, harsher than even than Indonesia’s following the Asian Financial Crisis. He maintained that the lessons have to be “seared into the collective consciousness,” and cited examples where remembering has positively shaped long-term economic behaviour. Germany’s aversion towards inflation, for instance, stems from the hyperinflation of the 1920s. The US Federal Reserve continues to be guided by the institutional memory of the Great Depression of the 1930s. Similarly, the willingness of the Chinese to trade certain freedoms for economic stability and growth reflects their desire to avoid a return to the chaos between the 50s and 70s.

A question from the audience challenged his argument, contending that Sri Lanka’s smaller scale, coupled with its exposure to repeated internal and external shocks, such as natural disasters, made comparisons with India inherently unfair. In response, he explained that his analysis was grounded in a broader economic framework, but he also invoked J.K. Rowling’s words: “There is an expiry date on blaming your parents for steering you in the wrong direction; the moment you are old enough to take the wheel, responsibility lies with you.” His point was clear: come what may, it is time for Sri Lanka to put its own house in order. Stability, he cautioned, is by no means assured, let alone sustained growth: “None of this is a guarantee against future crises, unless there is a broad consensus within Sri Lankan society that such outcomes must not be allowed to recur.”

This piece summarizes the speaker’s views and arguments and does not represent the author’s own opinions.