A Man Shaped by Psychology

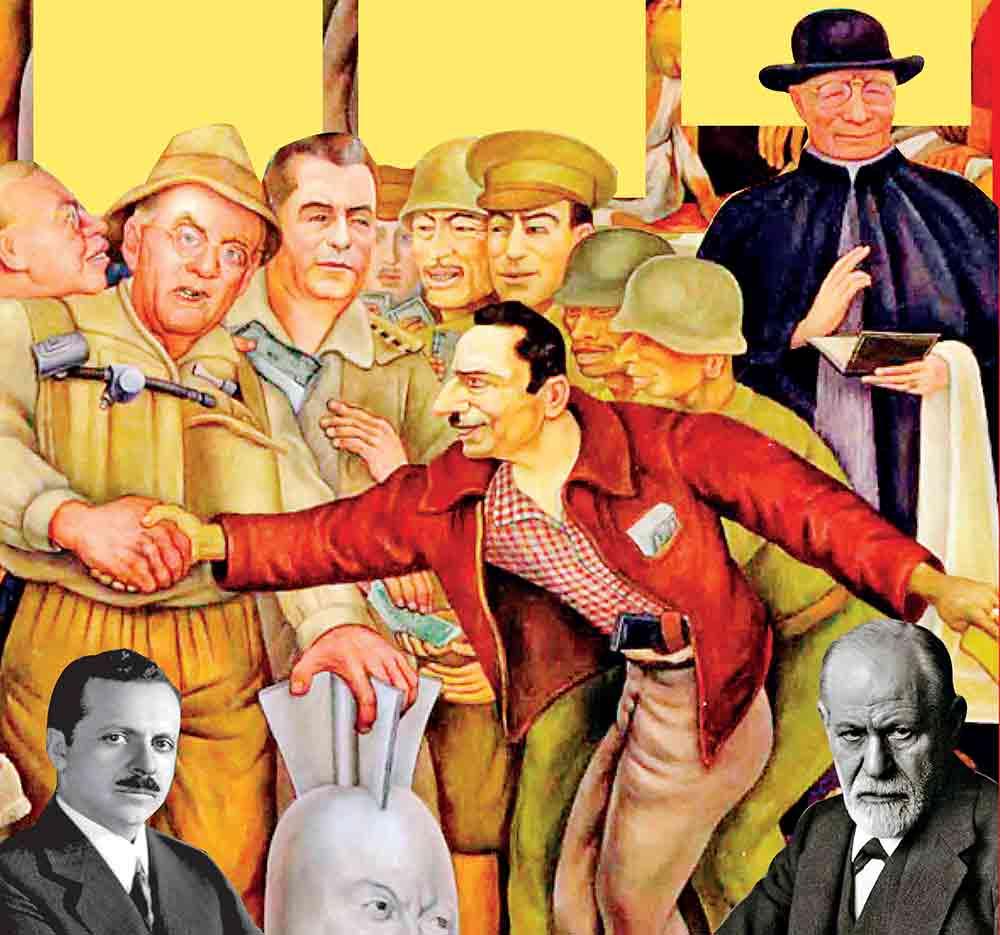

Edward Bernays was born in 1891 in Vienna, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His family emigrated to New York when he was still a child. He had a unique connection: he was the nephew of Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis. Freud explored the unconscious drives of individuals, fear, desire, sex, and status. Bernays realized these same impulses could be harnessed on a mass scale. Where Freud analysed the patient on the couch, Bernays turned psychology outward, toward the crowd. He once said he had taken his uncle’s insights “out of the clinic and into the marketplace.” That fusion of psychology with communication created an entirely new profession: public relations.

Edward Bernays was born in 1891 in Vienna, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His family emigrated to New York when he was still a child. He had a unique connection: he was the nephew of Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis. Freud explored the unconscious drives of individuals, fear, desire, sex, and status. Bernays realized these same impulses could be harnessed on a mass scale. Where Freud analysed the patient on the couch, Bernays turned psychology outward, toward the crowd. He once said he had taken his uncle’s insights “out of the clinic and into the marketplace.” That fusion of psychology with communication created an entirely new profession: public relations.Selling Breakfast, Selling Ideas

Bernays had a talent for turning everyday products into cultural touchstones. One of his lesser-known but striking campaigns was for the Beech-Nut Packing Company in the 1920s. Americans were eating light breakfasts of coffee, rolls, or fruit. Bacon sales lagged. Bernays surveyed doctors, asking whether a hearty breakfast was healthier than a light one. Many agreed. He then promoted the idea that a breakfast of bacon and eggs was scientifically endorsed. Newspapers picked it up. Soon, bacon and eggs were no longer just a product; they were an American tradition. This was Bernays’ approach: he rarely sold the product itself; he sold the story around it. And the story stuck.

Cigarettes and the Language of Liberation

The same strategy transformed the tobacco industry. In the 1920s, women were discouraged from smoking in public. For the American Tobacco Company, that meant half the market was closed. Bernays created a spectacle. At New York’s Easter Parade, he arranged for fashionable women to light cigarettes, branding them as “torches of freedom.” The press eagerly reported the event. Overnight, cigarettes were reframed as symbols of independence rather than impropriety. Facts about health were irrelevant. The story of empowerment carried the day. Bernays showed that products could be tied to powerful emotions and social currents. The mechanics mattered less than the meaning attached to them.

From Products to Politics

What set Bernays apart was his ability to transfer these methods from consumer goods to politics and global affairs. He understood that public opinion could be influenced not just to buy products but to accept policies, endorse leaders, or support interventions.

United Fruit and Guatemala

By the 1950s, United Fruit was one of the most powerful corporations in Central America, controlling land, railways, and shipping. In Guatemala, President Jacobo Árbenz introduced land reforms to redistribute unused land to small farmers. Though legal and compensated, the move threatened United Fruit’s monopoly.

Bernays was hired to manage the company’s public relations crisis. He knew he could not present it as a corporate dispute over land. Instead, he reframed it as part of the Cold War. Guatemala was portrayed not as a democracy pursuing reform but as a communist threat to the United States.

His strategy was multi-layered:

- He organized trips for U.S. journalists to Guatemala, carefully curated experiences with briefings, handpicked sources, and staged interviews.

- He distributed reports and bulletins to American politicians and editors portraying Árbenz as sympathetic to Moscow.

- He simplified the narrative into a story of freedom versus communism, stability versus chaos.

Major newspapers echoed these themes. Public opinion shifted. By 1954, the U.S. government saw Guatemala as a liability. The CIA staged a coup, and Árbenz was ousted. The outcome was decades of instability and violence. While the coup was military, Bernays’ communications campaign set the stage. It demonstrated that the tools of persuasion could alter geopolitics.

The Toolkit of Influence

Bernays’ methods were consistent across campaigns:

- Agenda setting: deciding which issues were highlighted and which were ignored.

- Framing: presenting issues through emotionally charged lenses such as freedom, security, or modernity.

- Credibility by proxy: relying on journalists, academics, or doctors to carry the message.

- Symbols and emotions: linking products or policies to deeply held values.

- Repetition: ensuring frames appeared repeatedly until they seemed like common sense.

From bacon and eggs to coups, the formula stayed the same.

Bernays and Democracy

Bernays defended his work as essential. He argued that democracy required professionals to guide opinion, seeing the public as too distracted or uninformed to make decisions without expert influence. He called this “the engineering of consent.” This phrase captures the paradox of his legacy. He professionalized communication and demonstrated its potential, but he also blurred the line between persuasion and manipulation.

Why This History Matters

The Guatemala story is not just a Cold War episode. It is a lesson in how narratives are created, amplified, and accepted as truth. Bernays’ techniques were not limited to one country or era, they became the DNA of modern public relations, political campaigns, and philanthropy.

Today, the lesson is not alarm but awareness. When a project launches with high-profile ceremonies, when a message is repeated across outlets, or when an issue is framed in stark emotional terms, these are signs of deliberate communication strategy. Awareness allows for better judgment.

Media in the Digital Age

The story is urgent today because media has transformed. In Bernays’ time, newspapers and radio were the gatekeepers. Today, algorithms determine what billions see on their phones. These algorithms reward speed, novelty, and emotion, deciding which headlines appear first, which videos trend, and which topics dominate conversation. The engineers of consent have been joined by engineers of code. The agenda-setting role once held by editors is now partly played by platforms, allowing misinformation to spread rapidly, sometimes outpacing corrections. Narratives can take root in hours, shaping perceptions before facts emerge.

Teaching the Next Generation

In this environment, media literacy is essential. Young people in Sri Lanka, as in every country, are immersed in social media curated by algorithms beyond their control. Teaching them to analyse, question, and verify is critical. Schools can integrate media literacy into curricula. Students can learn to check sources, spot framing, recognize repetition, and understand how algorithms amplify some stories while burying others. Emotional headlines spread faster than sober analysis, recognizing this is key. This is not about cynicism; it is about equipping the next generation to navigate the busiest information marketplace in human history. With these skills, young citizens are less likely to be manipulated and more likely to engage thoughtfully in public debate.

A Better Democracy Needs Media Literacy

Edward Bernays’ career stretched from selling bacon and eggs as the hearty breakfast, to branding cigarettes as symbols of freedom, to shaping international opinion about a small Central American country. His connection to Sigmund Freud gave him psychological insight, and his campaigns showed how these insights could be applied at scale. The story of United Fruit in Guatemala is not just about bananas. It is about how narratives are crafted, how perception can be reshaped, and how consent can be engineered. The techniques Bernays pioneered have only grown more powerful in the age of social media. The lesson for today is awareness, not alarm. Understanding how persuasion works makes us less likely to be swayed unknowingly. For Sri Lanka, as for any country, investing in media literacy and teaching the next generation to question and analyse is a safeguard against manipulation. Bernays sought to engineer consent. Our task is to engineer understanding. That is the foundation of a healthy democracy, one where citizens are informed participants, not passive recipients of narratives written elsewhere.