Introduction: The Paradox of Stone and Sword

Introduction: The Paradox of Stone and Sword

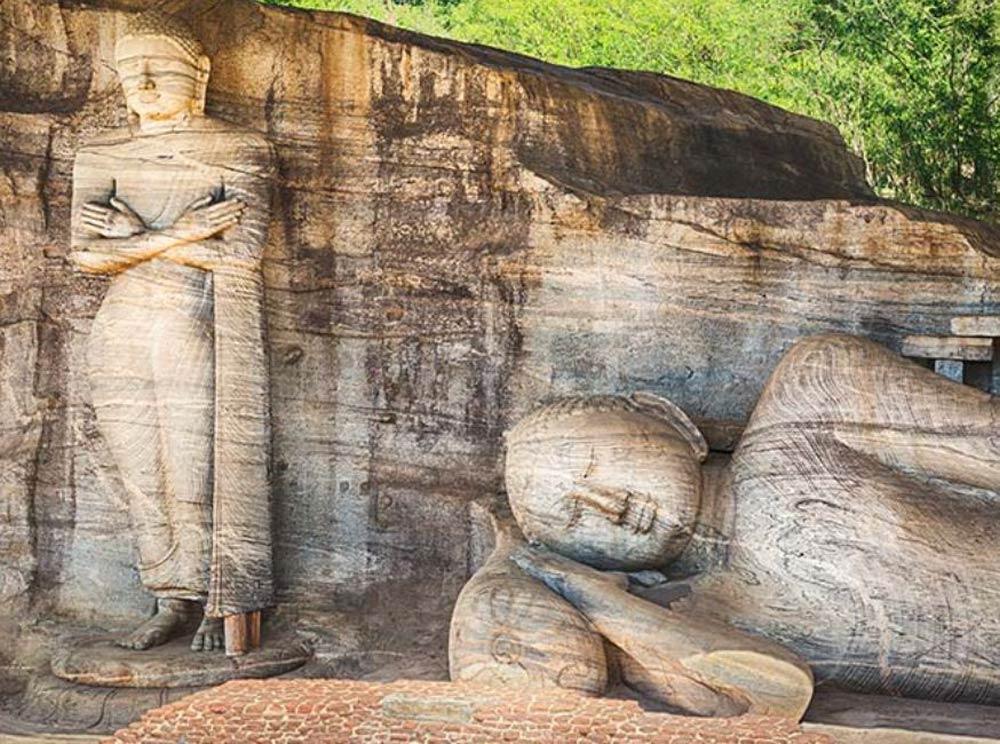

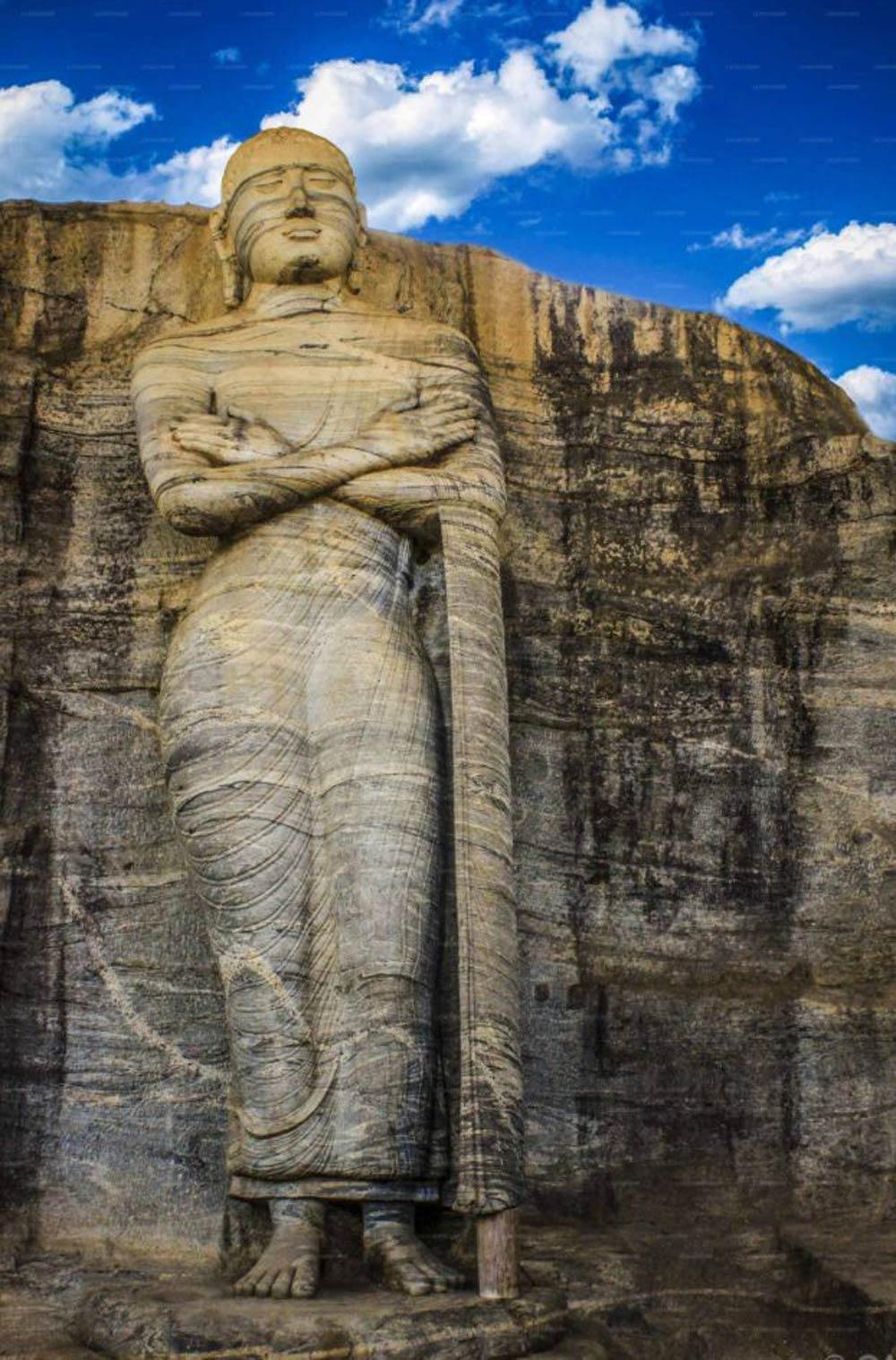

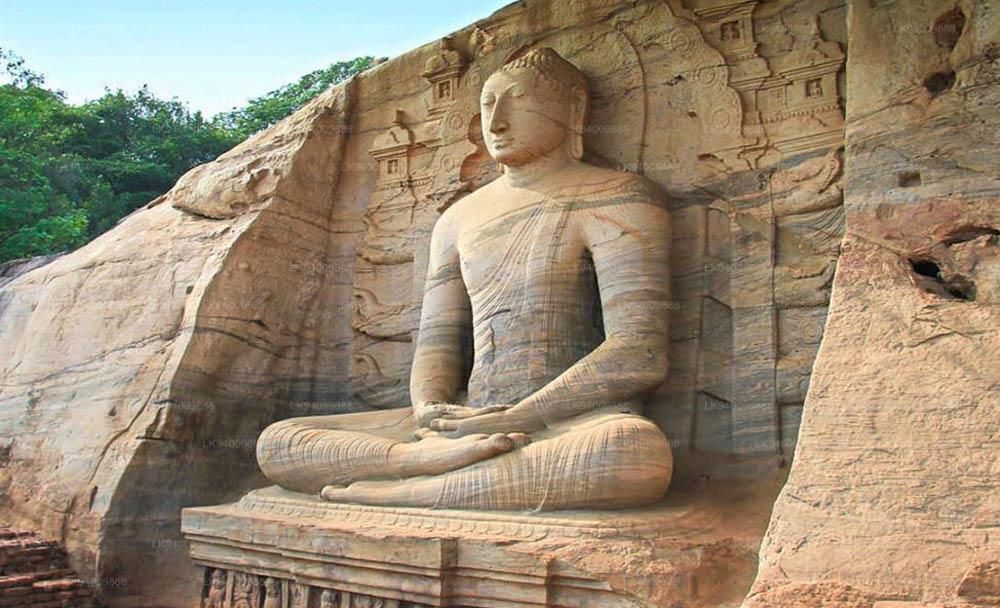

Polonnaruwa dazzles modern visitors with the serene faces of the Gal Vihāra Buddhas. Carved from a single granite outcrop, these statues embody tranquillity: a seated Buddha in meditation, a colossal figure standing in contemplation, and the long body of the Reclining Buddha, said to represent parinirvāṇa. To stand before them is to sense timeless peace. Yet the city that commissioned them was anything but peaceful. For behind these stone Buddhas lay a kingdom of relentless war. Polonnaruwa was the capital not only of irrigation tanks and monasteries, but of conquest, campaigns against the Cholas, raids into Burma, invasions from the Pandyas, and a perpetual cycle of rebellion and repression. Its rulers fought with sword in hand even as they inscribed their victories in the language of dharma. This is the paradox of Polonnaruwa: a city where kings cloaked violence in sanctity, turning war into holy duty and carving Buddhism into the very stones that watched armies march.

I. From Refuge to Empire

The rise of Polonnaruwa followed the decline of Anurādhapura, sacked by Chola invaders in the 10th century. Vijayabāhu I (1055–1110) expelled the Cholas, reclaimed sovereignty, and crowned himself in Polonnaruwa. Yet his reign was marked by constant struggle: consolidating a fractured kingdom, resisting fresh invasions, and securing the patronage of the Buddhist sangha. His successors inherited a capital that was still a frontier garrison at heart. Parākramabāhu I (1153–1186) transformed it into an imperial city, uniting rival Sinhala factions under his authority. But he did so not only through diplomacy or infrastructure; he did so through war, extending his armies beyond the island and into the Bay of Bengal. The chronicles praise him as Maha Parākramabāhu, “the Great,” a dharmarāja who restored the sangha, built tanks, and erected monuments. Yet his greatness rested equally on campaigns of violence that stretched the kingdom’s reach and strained its resources.

II. The Creed of the Dharmarāja

In theory, the Buddhist king was a righteous sovereign, a dharmarāja, who ruled by virtue rather than conquest. But in practice, the doctrine was malleable. To wage war was framed not as aggression but as the defence of dharma. The Cūḷavaṃsa, the continuation of the Mahāvaṃsa, describes Parākramabāhu reforming the sangha, expelling corrupt monks, and purifying the sasana. These acts are portrayed as religious merit, yet they were also strategies of control. A fractured monastic order meant fractured legitimacy; a unified order meant a unified kingdom. In this sense, every battle fought under his banner could be cast as holy; a war not for plunder, but for the preservation of Buddhism. The Gal Vihāra statues, carved under his patronage, embodied this sanctified kingship. The silent granite faces proclaimed a peace that only the king’s wars could supposedly guarantee.

III. Wars Across the Palk Strait

Polonnaruwa’s kings could never ignore South India. The Cholas had scarred the island; the Pandyas and Kalingas loomed as perpetual rivals. Parākramabāhu launched expeditions against them, sometimes in support of claimants to their thrones, sometimes in retaliation for raids. The chronicles tell of fleets constructed at Mahatittha, sailing north with elephants and infantry to intervene in Pandyan succession disputes. Archaeological finds of South Indian coins in Polonnaruwa testify to the depth of these exchanges, both violent and commercial. Nissankamalla (1187–1196), a later king, boasted of campaigns into the Deccan, inscribing his claims in bombastic prose. While modern historians question the scale of these exploits, the point remains: kings of Polonnaruwa presented themselves as conquerors, legitimized by the mantle of Buddhist kingship.

IV. Campaigns Beyond the Seas

Perhaps the most striking paradox lies in Sri Lanka’s ventures across the Bay of Bengal. Parākramabāhu dispatched an expedition to Burma (then Rāmañña), ostensibly to punish insults against Sinhalese merchants and to restore the honor of the tooth relic. His forces, carried on ships built for war, devastated coastal towns before withdrawing. Here was Buddhism transformed into a casus belli. The king who carved serene Buddhas into granite justified foreign conquest as the defence of relics and the faith. This duality, of sanctity and savagery, defined Polonnaruwa’s self-image. To foreign courts, the king projected himself as a patron of the sasana; to his own people, he proved himself as a protector who wielded the sword.

V. The Gal Vihāra: Serenity as Propaganda

The Gal Vihāra statues are not merely art; they are ideology in stone. Commissioned during Parākramabāhu’s monastic reforms, they represent a vision of Buddhist unity. The seated Buddha in samādhi conveys meditation, the standing figure conveys compassion, and the reclining image conveys release. Yet these images were created in the same reign that saw armies dispatched overseas and rivals crushed in battle. Their serenity is not an escape from violence but a response to it. They suggest that true peace is possible only under a righteous ruler who fights to secure it. As art historian Ananda Coomaraswamy observed, the Buddhas of Polonnaruwa are serene precisely because they preside over a turbulent world. Their stillness was meant to reassure, that the chaos of war served a higher order, and that conquest itself could be sanctified.

VI. Collapse and Consequence

The paradox of holy war could not last. Within a century of Parākramabāhu’s death, Polonnaruwa was undone by the very logic of conquest. Successors overreached, the hydraulic system faltered, and fresh waves of invasion battered the capital. The city’s grandeur proved fragile; its wars unsustainable. By the late 13th century, Polonnaruwa was abandoned. The jungle reclaimed its palaces; the irrigation channels silted. What endured were the Buddhas — silent witnesses to a kingdom that justified war in the language of peace.

VII. Reading Polonnaruwa’s Holy Wars

Polonnaruwa forces us to confront uncomfortable questions. Can a king be both dharmic and violent? Can conquest be sanctified if it claims to protect religion? For medieval Sri Lanka, the answer was yes. Kingship required both temple and battlefield, both relic chamber and war camp. Historians such as Wilhelm Geiger and K. M. de Silva have emphasized the pragmatism of these rulers, while more recent scholars like Nadeesha Gunawardana have pointed to the functional intertwining of monastic and military authority. The chronicles, of course, veil violence in piety, yet the ruins remind us of the reality: armies marched, elephants trampled, ships burned, even as Buddhas smiled from stone.

Conclusion: A Kingdom’s Double Legacy

To walk through Polonnaruwa today is to feel two histories at once. On one side, the calm of the Gal Vihāra, where visitors whisper in reverence before the eternal calm of the Buddha. On the other, the silence of ruined palaces and overgrown tanks, once shaken by the noise of war. This is Polonnaruwa’s double legacy. It was a kingdom that built peace in stone while pursuing war in the field, that turned conquest into merit and sanctified violence as protection of the sasana. Its lesson is both sobering and timeless: that even the most sacred images can be forged in the shadow of swords.