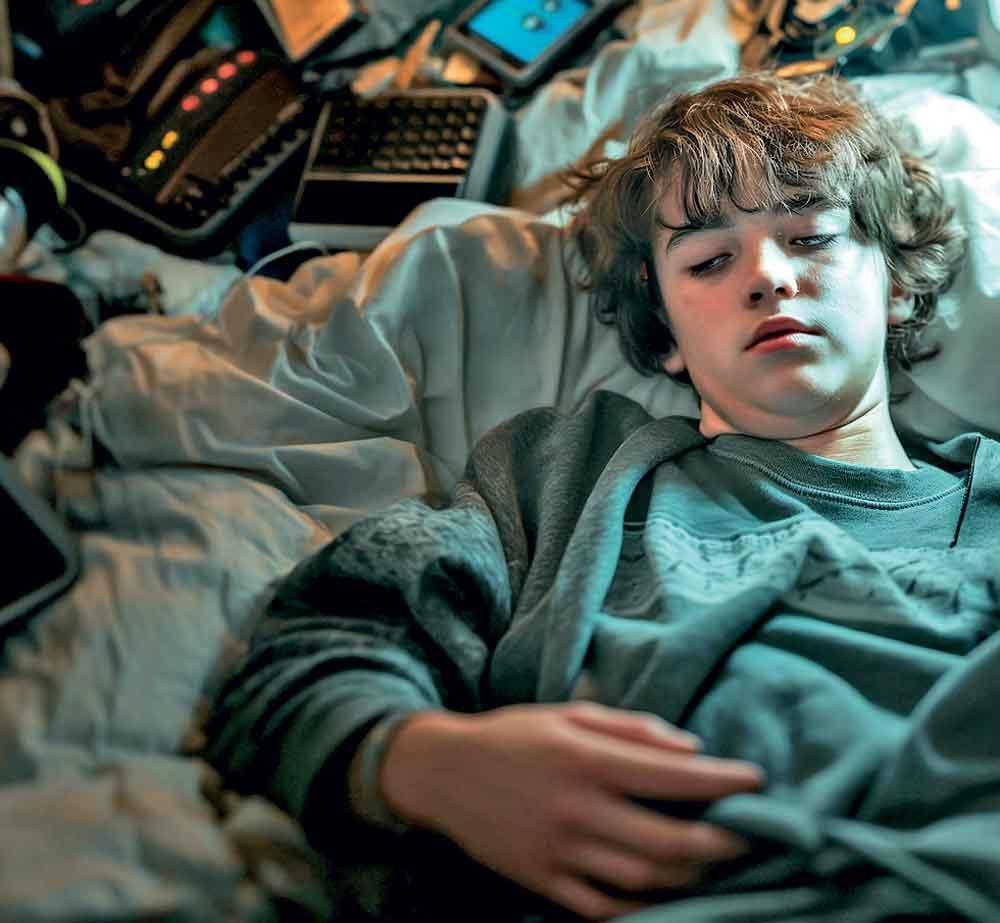

Adolescence is often dismissed as a period of rebellion, moodiness, and recklessness. But growing evidence suggests that much of what we attribute to “teen angst” may actually stem from chronic sleep deprivation. A landmark new study by the University of Georgia reveals that teens who do not get enough sleep experience measurable changes in their brain structure—changes that correlate with impulsivity, aggression, and broader behavioral issues. This compelling evidence reframes the public dialogue: insufficient sleep is not a trivial inconvenience, but a significant threat to adolescent brain development. As such, we must ground policies, parenting practices, and school schedules in neuroscience, not stereotypes.

The Science: Sleep Shapes the Adolescent Brain

Thirteen- to eighteen-year-olds are in the midst of crucial brain maturation. Neural networks responsible for decision-making, impulse control, and emotional regulation—predominantly in the prefrontal cortex—are actively developing. Sleep, it turns out, is not facultative; it’s crucial. A recent study involving 2,800 adolescents, tracked via wearable Fitbits and MRI scans, found that shorter sleep duration and lower sleep quality lead to reduced connectivity in these critical brain circuits. Teens with disrupted networks exhibited heightened impulsivity, aggression, and conduct problems.

These findings validate the dual-systems model of adolescent development: while emotional and reward pathways mature rapidly, the prefrontal control systems lag—making teens neurobiologically vulnerable . Without sufficient sleep, the imbalance becomes exacerbated: risk-taking intensifies, and executive function declines. Thus, sleep deprivation compounds an already sensitive period.

Real-World Consequences: Beyond Theory to Action

This is not just theoretical science. Teens functioning on fewer than the recommended 8–10 hours per night show more impulsive behaviors, like reckless driving, substance use, and poor emotional regulation . The CDC reports that over 70% of high schoolers are sleep-deprived, with nearly 40% sleeping six hours or less. Sleep loss correlates with impulsivity in everyday scenarios: pronounced risk-taking, diminished judgment, and even poorer academic performance.

Moreover, poor sleep worsens emotional health. Studies confirm links to anxiety, depression, and even psychosis symptoms . ADHD, too, is entangled with sleep deficits; teens with ADHD often fall asleep later, sleep less deeply, and endure more nighttime awakenings, which in turn amplify hyperactivity and poor impulse control. The connections are clear: when the brain is not well-rested, steering impulses becomes exponentially harder.

Sleep Deficit Is Not Innocuous—it’s Preventable

It’s tempting to label teen sleep loss a “lifestyle issue”—after all, screens, homework, jobs, and social pressure all contribute. However, blaming teens or families ignores systemic failings. Instead, lack of sleep operates as a public health crisis with neurodevelopmental consequences. The question is not if sleep matters, but how society will respond.

Consider school start times: despite solid evidence from longitudinal studies showing how delaying start times improves attendance, performance, and mental health, many schools continue with early start times. The idea that teens are naturally wired to sleep late and wake late is backed by science—not sloth. Yet outdated schedules turn biology into dysfunction.

Opposing Views: Are We Overreacting?

Critics may argue that teens have always pulled late nights, that smartphones are just more visible mirrors of normal adolescent behavior, not causes. Some worry that early school starts instil discipline and preparation for adult schedules. Others posit the data is correlative—maybe impulsivity leads to late nights, not vice versa.

Yet the most rigorous data argue otherwise. The UGA study controlled for baseline temperament and found sleep disruption preceded—and predicted—behavior issues over two years, supporting causality . Meanwhile, longitudinal analyses show poor sleep predicts worsened inhibitory control, heightening risk of future mental health challenges and even psychosis. Sleep is not a bystander; it’s a driver.

Further, interventions like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) have reversed some effects, improved inhibitory function and reduced anxiety . Shifts in school policy have yielded positive outcomes, reinforcing that structured change—rooted in science—can make a meaningful difference.

Taking Action: What Should We Do?

To adapt to the evidence, society must act in three domains:

- Public Policy & Education Reform

Schools should start no earlier than 8:30 AM, aligning with natural adolescent circadian rhythms.

Curriculum should include lessons on sleep hygiene—limiting evening screen use, caffeine, and ensuring consistent bedtimes.

- Medical & Behavioral Interventions

Clinics treating ADHD or depression in teens must screen for sleep disorders; poor sleep is both a symptom and exacerbator.

CBT-I and other sleep therapies must be made accessible and medically reimbursed.

- Parental & Community Engagement

Parents must appreciate that teen moodiness often reflects sleep debt, not defiance. Monitoring and modeling bedtime routines matter.

Communities should encourage teen-friendly spaces that discourage nighttime stimulation—whether malls or sports—and reevaluate extracurricular timings.

Rebutting Objections

Some may claim these measures infringe on individual freedom or burden underfunded school districts. But the cost of inaction—rising teen mental illness, vehicle crashes, drug use, disciplinary issues—is far greater. A modest investment in later start times and sleep programs pays dividends in reduced healthcare burdens and improved academic performance.

Others maintain school inertia is stubborn, tied to bus schedules and athletics. Yet pilots from districts like Minneapolis demonstrate that community-driven change is feasible—and effective . It’s time to treat sleep not as a luxury, but a priority.

Conclusion: A Wake-Up Call

We discipline teens for behavior that science links to under-slept brains, yet do little to address root causes. The UGA findings and corroborating studies suggest a simple truth: adequate sleep is essential for the maturation of impulse control, emotional stability, and healthy behavior. Marking teen sleep as a personal failing does none of us any good; understanding it as a neurodevelopmental necessity opens pathways for compassion, science-informed policy, and better health.

We stand at a crossroads. Either we continue to pathologize teen behavior without examination, or we accept that sleep deprivation damages young brains—and act accordingly. Advocating for later school starts, public education, therapy access, and family support isn’t coddling; it’s respecting biology. If we truly value our youth’s potential, we won’t ask them to burn the candle at both ends. We’ll give them the rest they need and a fighting chance at healthy adulthood.

Call to Action: Change Isn’t Optional

We must champion policies—locally, nationally—that enshrine sleep as a human right for developing teens. Educators, physicians, parents, and policymakers share responsibility. Let’s stop blaming teens for struggling to flourish on starvation-level sleep. Instead, let’s redesign our institutions around their needs. If not now, when?