The use of water clocks in ancient Anuradhapura is most clearly understood in its religious setting. Monastic communities required strict adherence to canonical hours for chanting, meditation, and almsgiving.

1

Time Before the Tick: Lanka’s Forgotten Chronology

Time Before the Tick: Lanka’s Forgotten Chronology

In the ancient kingdom of Anuradhapura, time did not tick; it dripped. Before the advent of mechanical clocks or European chronometers, the governance of life, faith, and ritual in Sri Lanka was regulated by a subtler, older rhythm. That rhythm was water. From at least the early centuries BCE, evidence suggests that water clocks, or clepsydrae, were used across parts of the island to regulate sacred and administrative timing. These devices, often hemispherical vessels with calibrated holes, measured time through the slow, controlled flow of water. In a civilisation that mastered the hydraulic manipulation of landscape, it should come as no surprise that it also measured time in liquid precision. Yet these clocks were more than instruments. They were ritual regulators, woven into the cosmology of the Sinhala Buddhist state. The passage of time itself became part of the moral order that kings and monks co-produced measured not in minutes, but in merit.

2

Ceremonial Flow: Water as Calendar and Clock

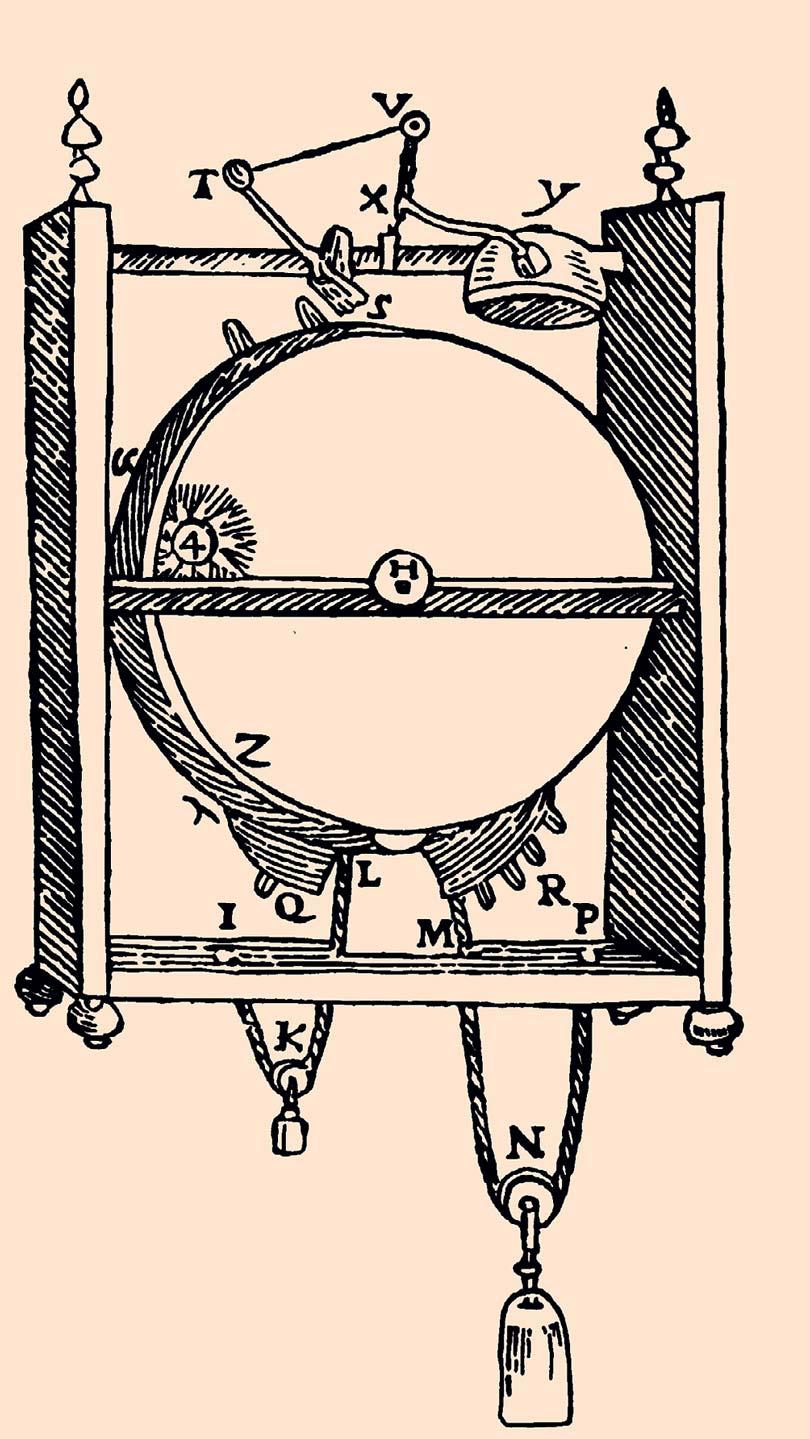

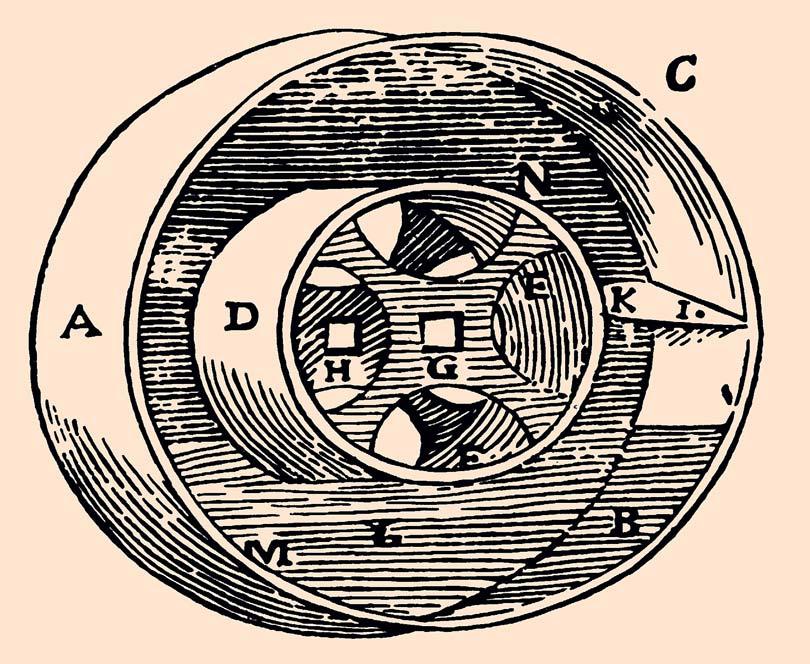

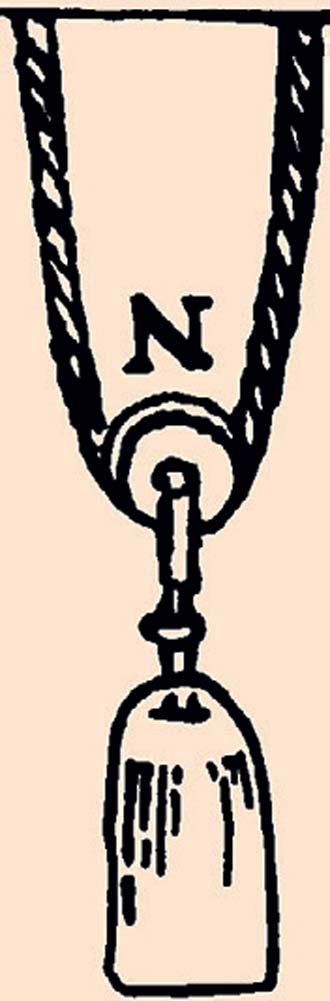

The use of water clocks in ancient Anuradhapura is most clearly understood in its religious setting. Monastic communities required strict adherence to canonical hours for chanting, meditation, and almsgiving. In the absence of mechanical devices, water clocks provided an effective and symbolically resonant tool. Scholars such as J.M. Katupotha et al. (2018) have proposed that the bowl-type clepsydra was likely used within temples and royal precincts. A small bowl, perforated at the base, would float in a larger basin of water. As it gradually filled and sank, the ritual hour would be marked. The method, described in both Indian astral science and South Asian ritual manuals, permitted an observable and reliable means of timing, even during nightfall or monsoon-obscured days. The Buddhist Sangha of Anuradhapura, closely aligned with the monarchy, did not merely adopt clepsydras out of necessity. These devices symbolised order and impermanence; two core tenets of the Theravāda worldview. Time, here, was not an abstract force but a measurable flow, to be attended with care and reverence. Rituals such as the Katina Robe Offering or Poya Day observances required exact timing, often coordinated across multiple temples. Water clocks would have ensured that the moments of offering, chanting, and cosmic alignment coincided correctly, preserving the moral geometry of the island’s spiritual topography.

3

Clepsydrae Without Ruins: Archaeology of the Invisible

Unlike stone monuments or bronze statues, water clocks do not fossilise easily. Made from clay, wood, or thin metals, their materials were often ephemeral, leaving behind scant direct archaeological remains. But absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. Ritual spaces such as Mihintale, Thuparama, and Isurumuniya show signs of temporal regulation. Many stupas and image houses are constructed along cardinal lines or in alignment with lunar phases, suggesting a ritual calendar that demanded observance to precise moments.

Recent archaeoastronomical studies, especially those by Katupotha, have identified possible solar and lunar alignments in key structures at Anuradhapura, hinting at an integrated system of cosmic architecture and ritual timekeeping. The clepsydra, while physically lost, persists in the logic of space.

4

Kings Who Commanded the Hour: Time as Statecraft

Chronicles such as the Mahāvaṃsa and Dīpavaṃsa often reference kings performing religious acts “at the proper time.” This is not merely poetic. Timing in ritual was an index of righteous kingship. To delay a consecration, mistime a festival, or misalign an offering was to risk disorder, both earthly and cosmic. Kings such as Devanampiya Tissa, Dutugemunu, and Mahasena are described as scrupulous in their observance of calendrical rites. The implication is not simply that they were devout, but that they mastered the architecture of sacred time. Anthropologist Tissa Widger argues that in ancient Sri Lanka, ritual timekeeping was a hydro-political act. Just as kings governed the flow of irrigation, so too did they govern the flow of sacred hours. The water clock, then, became a microcosm of sovereignty; a vessel through which kings co-ruled time itself with the monastic order. Such instruments may also have had judicial or administrative functions. Court sessions, temple distributions, or seasonal announcements may have all been synchronised through clepsydra use, subtly linking kingship with cosmology.

5

Temporal Sovereignty: The Clock as a Metaphysical Tool

In Buddhist metaphysics, time is both cyclical and transient. The clepsydra perfectly mirrors this worldview: time flows steadily, inevitably, but without noise or violence. It does not tick but recedes. Comparative scholars like Sheldon Pollock have written about the ritualisation of time in Indic polities, where astronomical, ritual, and statecraft logics often converged. Sri Lanka’s water clocks, although less directly documented, align perfectly with this paradigm. Time was not neutral; it was structured and moralised. The Sangha’s discipline (Vinaya), the king’s ritual obligations, and the agricultural cycle were harmonised through devices like the clepsydra. This was a sacred technology, one that encoded the political order in each drop. In a civilisation that canalised rivers and built tanks of astonishing scale, channelling time became a parallel expression of power and devotion.

6

Conclusion: To Rule Time Is to Ritualise Power

The ruins of Anuradhapura speak in stone; stupas, moats, carvings. But beneath that visual grammar lies a temporal architecture, one which has faded more subtly. The clepsydra, though lost to decay and time, shaped the very experience of both. Water moved the state. Water moved time. And in that movement, kingship and monasticism found mutual rhythm. To understand Anuradhapura is not only to read its bricks or count its ponds. It is to imagine the quiet bowl floating at dusk, slowly sinking. It is to hear the splash that marked the sacred hour. And in that sound, to rediscover a kingdom that once ruled the clock, not through gears and bells, but through silence

and flow.