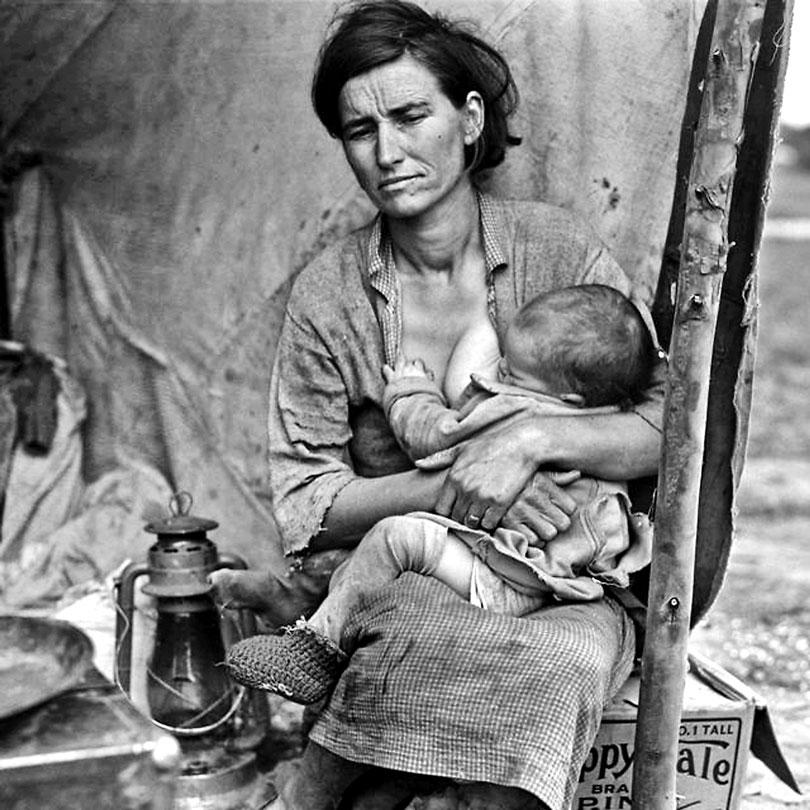

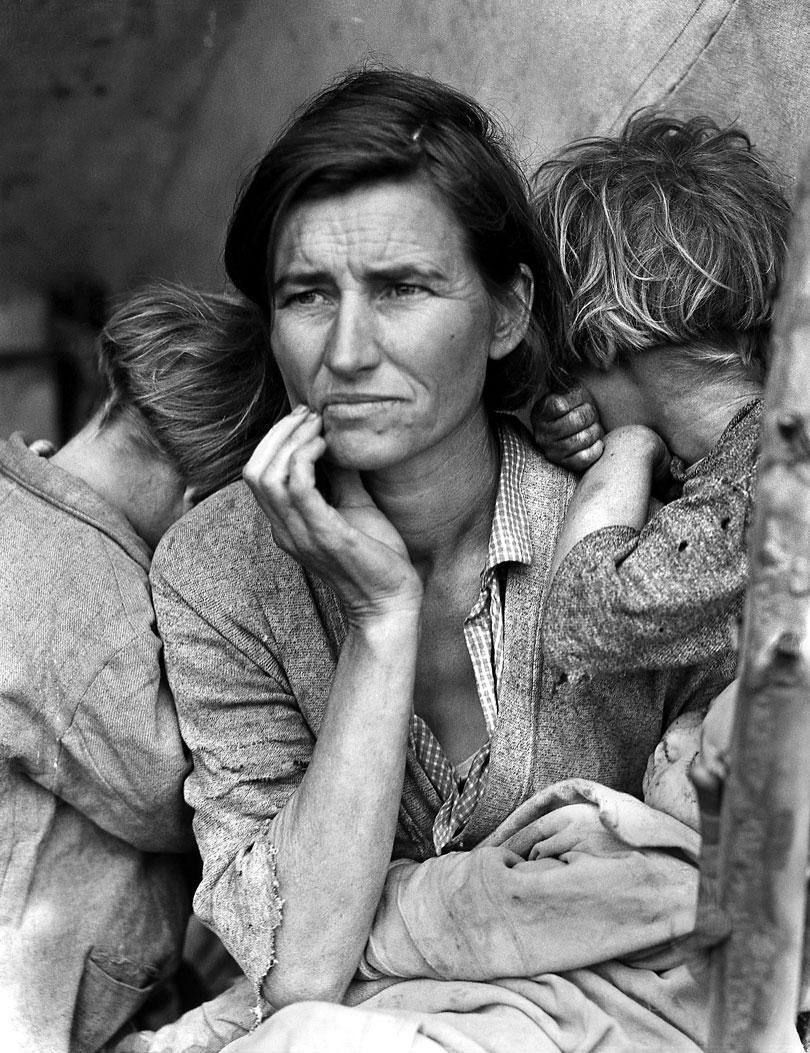

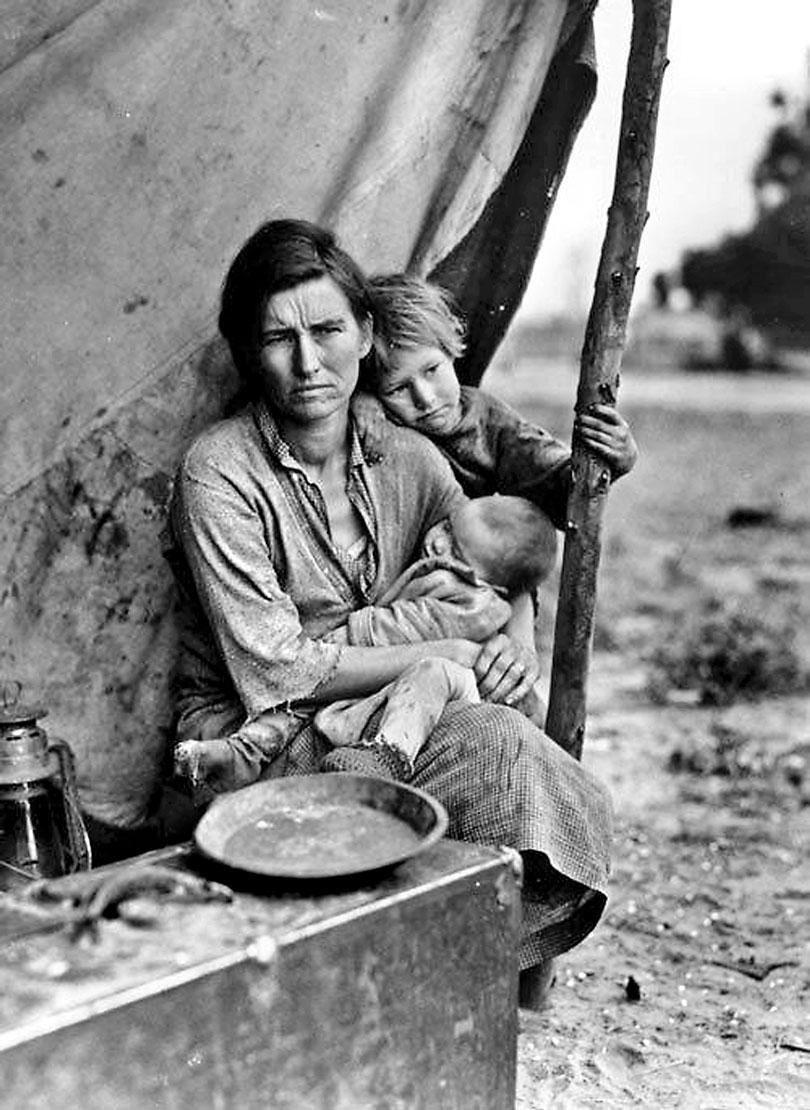

Florence Owens Thompson.

"Migrant Mother" by Dorothea Lange

Yet behind the iconic photograph was a real woman with her own story; a woman who didn’t ask to be the face of a movement but became one nonetheless.

Dorothea Lange’s choice to photograph in black and white heightened the emotional gravity of the image. The absence of colour stripped away distractions and emphasized the facial expression of the mother, the furrowed brow, the distant gaze, the set jaw.

|

Photographer Dorothea Lange |

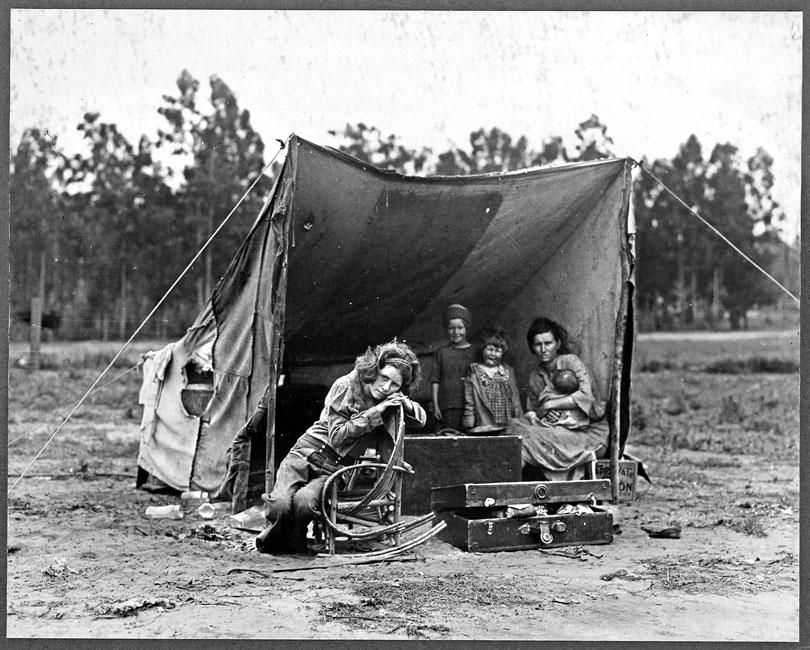

In the spring of 1936, during one of the darkest chapters in American history, a photograph was taken that would go on to capture the heartache and perseverance of an entire generation. The image, now known around the world as Migrant Mother, was taken by photographer Dorothea Lange while working in Nipomo, California. In it, a woman gazes into the distance with a look of deep worry and quiet strength. Her baby rests in her lap while two older children lean into her shoulders, their faces turned away from the camera. It is a haunting portrait, one that came to define the human cost of the Great Depression.

At the time the photograph was taken, the identity of the woman in the image was unknown. She was simply a face among the many victims of economic collapse, drought, and widespread poverty. For more than forty years, her name remained a mystery. It wasn’t until 1978 that a journalist from The Modesto Bee uncovered her identity. Her name was Florence Owens Thompson.

Lange had been commissioned by the Farm Security Administration (FSA), a government agency formed under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. The FSA aimed to provide aid to rural farmers devastated by the economic downturn and the Dust Bowl, which turned fertile land into dust, crippling agriculture across vast regions of the country. Lange’s mission was to document the lives of people affected by this crisis, using photography to raise awareness and generate public support for government aid.

In March of 1936, after completing a photo assignment in California, Lange was on her way home. The weather was dreary and wet, and she was exhausted. But as she passed a hand-painted sign that read “Pea Pickers Camp,” something told her to stop. Compelled by instinct, she turned her car around and followed the sign into a makeshift camp of destitute workers. That’s where she found Florence Thompson and her children.

Later, Lange would describe the encounter as magnetic. “I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet,” she wrote. Thompson and her children were living in a temporary shelter made of canvas and sticks, surviving on scraps, frozen vegetables salvaged from nearby fields and small birds her children had managed to catch. Lange took six photographs of the family, carefully documenting the raw reality of their lives. One image, in particular, stood out and soon became iconic.

The photograph was quickly circulated through newspapers and magazines across the country. It stirred a national response, sparking outrage, compassion, and action. Within days of its publication, the U.S. government sent 20,000 pounds of food to the migrant labour camp in Nipomo. The power of the image lay not just in its composition, but in its emotional honesty, it captured the pain of poverty, the vulnerability of motherhood, and the quiet endurance of a woman trying to hold her family together.

Yet, Florence Thompson’s version of the story adds a layer of complexity to the narrative. Many years after the photo was taken, she shared her memories of that day. According to her, Lange didn’t spend much time with her or her family. She felt that Lange had fabricated parts of the story, such as the claim that Florence had sold her car’s tires to buy food. Thompson insisted that she still had the car and that the story had been embellished for dramatic effect.

To Florence, the photograph was not a proud symbol, it was a painful reminder of a time when she had nothing and no privacy. She never sought fame, nor did she benefit financially from the image that made her face internationally recognizable. But her children saw things differently. They believed the photograph elevated their mother into a symbol of strength, sacrifice, and resilience. They saw the image not as an invasion of privacy, but as a testament to the dignity with which she faced adversity.

Dorothea Lange’s choice to photograph in black and white heightened the emotional gravity of the image. The absence of colour stripped away distractions and emphasized the facial expression of the mother, the furrowed brow, the distant gaze, the set jaw. With the children’s faces turned away, all attention is drawn to Thompson’s face, which speaks volumes about fear, responsibility, and unspoken resolve.

Lange saw photography as a tool for social justice. “The camera is an instrument of democracy,” she once said. Her work with the FSA was driven by the belief that powerful imagery could change minds and mobilize action. In Migrant Mother, she succeeded in capturing a universal truth about struggle, motherhood, and human dignity. The image gave a voice to the voiceless, shining a light on people who were often ignored or forgotten.

Florence Thompson, by contrast, was simply trying to survive. Her life was not lived in pursuit of symbolism or recognition. She was a mother of seven children, navigating one of the harshest periods in American history with limited resources and boundless determination. Her inclusion in Lange’s photograph was not by design, it was a moment captured in passing, a split second that would go on to shape how future generations understood the Great Depression.

Today, Migrant Mother hangs in the Museum of Modern Art in New York City and continues to resonate with viewers around the world. It is not just a portrait of a single woman, but a window into the collective experience of millions. It reminds us of the fragility of life during economic disaster, and the extraordinary strength ordinary people summon in the face of overwhelming hardship.

While the photograph immortalized Florence Thompson’s image, it also sparked lasting debates about the ethics of photojournalism, the power of narrative, and the line between documentation and storytelling. Lange’s image remains one of the most reproduced photographs in history, studied in classrooms, printed in textbooks, and featured in exhibitions. Yet behind the iconic photograph was a real woman with her own story; a woman who didn’t ask to be the face of a movement but became one nonetheless.

In the end, Migrant Mother is both a work of art and a piece of history. It’s a snapshot of an era defined by suffering, resilience, and the pursuit of hope. Through the lens of Dorothea Lange and the unintentional legacy of Florence Thompson, the photograph continues to speak to the enduring human spirit. It reminds us that even in the bleakest of times, there are faces that shine with courage, and stories that need to be told.