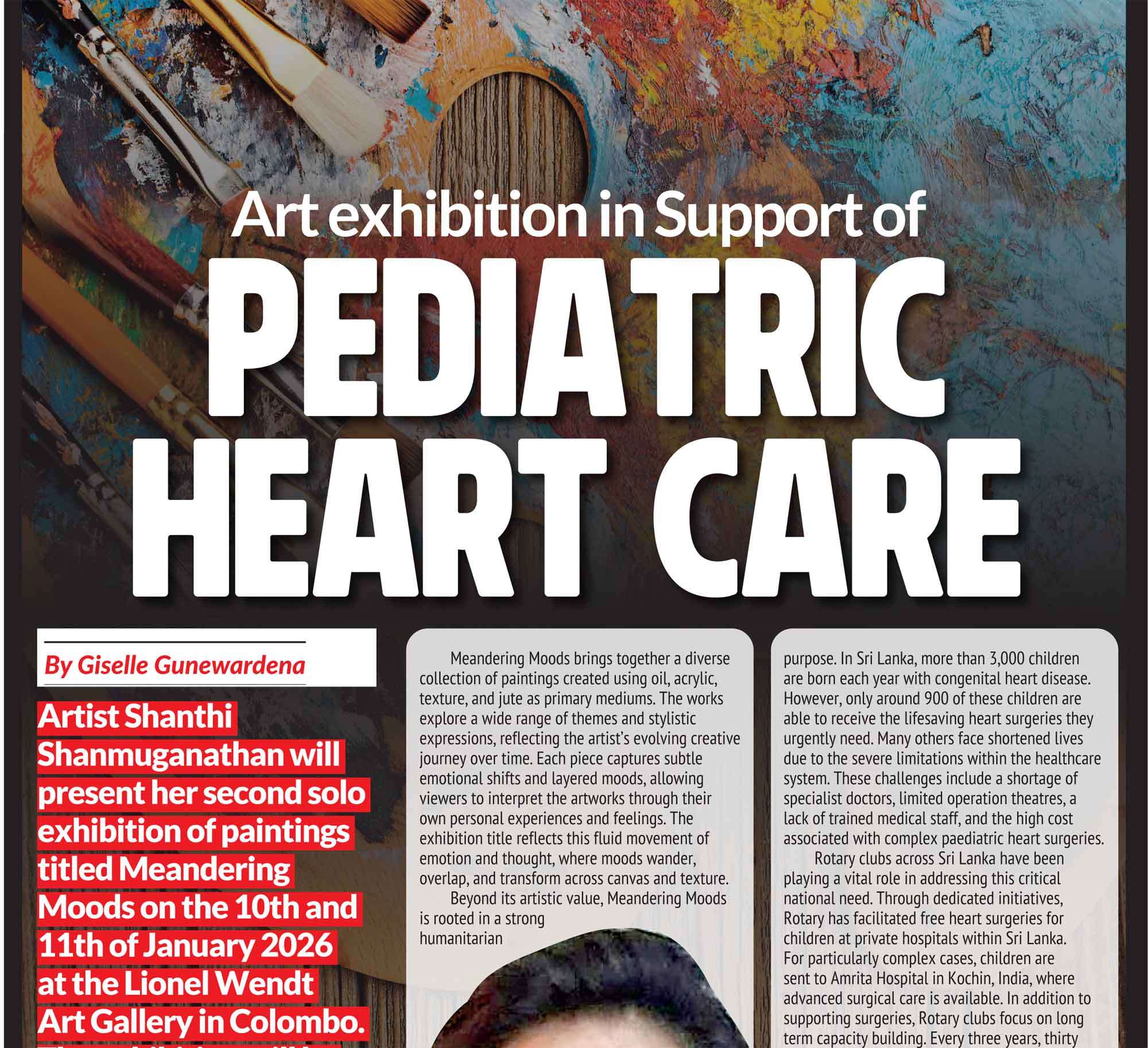

Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) is a practice that continues quietly within some of our communities. It’s whispered about in living rooms, dismissed by some as “just a nick,” and denied entirely

by others.This column isn’t here to accuse communities. It's not here to sensationalize pain or point fingers at faith. What Behind Closed Doors will do is lay out, plainly and clearly, what has been pushed to the margins for too long.

In Sri Lanka, we love the idea of peace. We've paid for it dearly, through war, displacement, distrust, and loss. Today, the language of reconciliation and unity is deeply stitched into our political fabric. But when peace becomes a reason to stay silent, especially about harm being done in the shadows, we have to ask: what kind of peace are we really preserving?

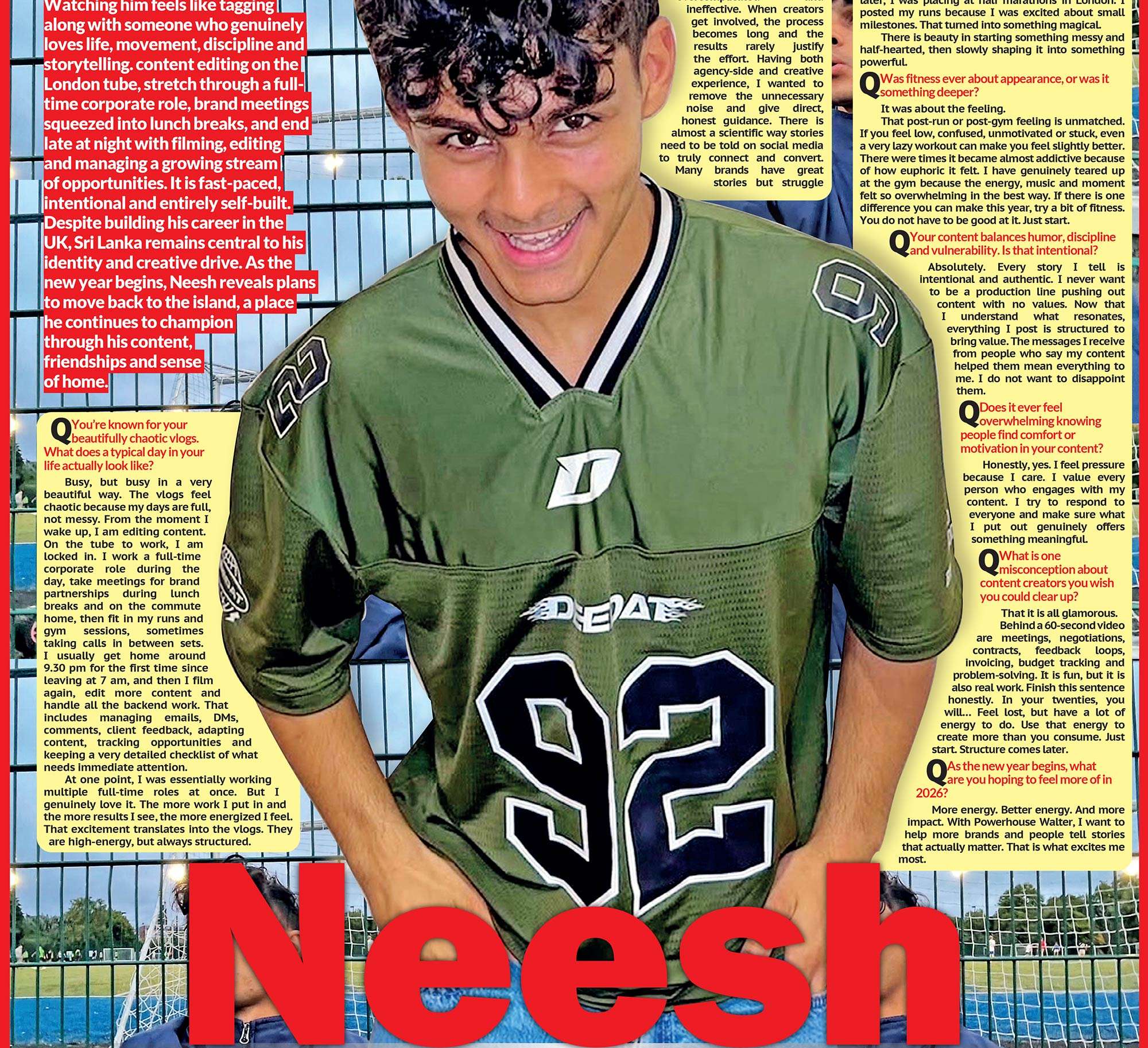

1

Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) is a practice that continues quietly within some of our communities. It’s whispered about in living rooms, dismissed by some as “just a nick,” and denied entirely by others. Many still don’t even realize it’s happening here, because it's tucked neatly behind a veil of cultural custom, medical ambiguity, and religious misinterpretation.

Across several regions in Africa and Asia, circumcision, both male and female, has long been carried out as part of cultural or religious traditions. But while male circumcision often receives religious or medical framing, the cutting of female genitalia, more commonly known as Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) or Female Genital Cutting (FGC), is increasingly recognized as a human rights violation. It’s a deeply controversial practice that has far-reaching physical and psychological consequences for women and girls, and one that global health bodies, activists, and survivors continue to fight against.

I’ve had the privilege of speaking with activists, lawyers, and medical professionals who’ve been working on this issue far longer than I have. And they all echo the same obstacle. Not lack of evidence, not lack of harm, but a profound fear of political weaponization. Talk about FGM, and suddenly you're accused of attacking a community, disrespecting faith, or “causing unrest.” Talk too loudly, and you're framed as someone trying to stir ethnic tension in a country still healing from its wounds.

And so, the silence wins.

But behind closed doors, little girls are still being cut, without consent, without explanation, and with lifelong consequences to their bodies and sense of self. The fact that this is still debated as a "cultural issue" and not a human rights violation speaks volumes about who gets to speak, and who must stay silent.

This column isn’t here to accuse communities. It's not here to sensationalize pain or point fingers at faith. What Behind Closed Doors will do is lay out, plainly and clearly, what has been pushed to the margins for too long.

This is not an attack on religion. This is not a political campaign. This is an urgent call to recognize that tradition, when it causes irreversible harm, needs to be re-examined. Full stop.

2

Understanding FGM in Sri Lanka

When most people hear the term FGM, they think of Africa or the Middle East. Few associate it with South Asia, let alone Sri Lanka. But here, too, it exists, quietly endorsed, medically misrepresented, and protected under the guise of culture. FGM, or more specifically what is practiced in parts of Sri Lanka, involves the cutting or nicking of a girl’s genitals, often when she is a baby or a toddler. Though it may not be as extreme as the forms practiced elsewhere, its consequences are no

less real.

Survivors report a range of physical and psychological aftershocks, from chronic pain and infections to a sense of violation, fear, and confusion that stays well into adulthood. Many only discover what happened to them when they grow older and compare experiences, or when they begin to explore their own anatomy and realize something isn’t right.

3

The Role of Silence and Shame

What keeps FGM protected is not just religious misinterpretation or misguided tradition, it's the heavy burden of shame. Families don’t speak of it. Girls don’t know how to question it. And in some cases, women who oppose it fear speaking out because they’ll be seen as betraying their community. The silence is not passive; it is enforced.

Even in urban, educated circles, many people remain unaware that this practice exists in Sri Lanka. And those who do know often dismiss it with phrases like, “It’s just a symbolic cut” or “It’s not as bad as in other countries.” But these justifications miss the point: any non-consensual alteration of a child’s body, especially one that causes pain or trauma, is a violation. Period.

4

The Political Dilemma

Sri Lanka is in a delicate political state. The government champions a narrative of national unity, peacebuilding, and reconciliation. This makes sense. We are still recovering from decades of ethnic conflict. But in this climate, issues that involve specific religious or ethnic groups become too "sensitive" to touch.

Activists trying to bring FGM into national conversation have found themselves blocked not just by religious institutions but by political ones as well. Lawmakers fear backlash, not just from conservative sections of society, but from opponents waiting to pounce on any perceived "attack" against minority communities. The result? A paralyzing kind of inaction. Everyone knows it's happening, but no one wants to be the first to say it out loud.

This fear is not unfounded. We live in a time when a headline or a soundbite can be twisted, taken out of context, and weaponized. But avoiding the issue is not a solution, it is complicity.

5

Cultural Sensitivity vs. Human Rights

Turning this into a series, Behind Closed Doors, will tread the line between cultural understanding and human rights advocacy. We must acknowledge that some people truly believe they are doing what is right, what has been passed down for generations.

But belief alone does not justify harm. Traditions, no matter how deeply rooted, must be interrogated when they conflict with bodily autonomy, consent, and basic health. Many Islamic scholars around the world have clarified that FGM is not required by religion. In fact, leading Muslim-majority countries and religious bodies have actively condemned it. It is crucial that we separate religion from cultural practices masquerading as religious duty.

6

A Call for Responsible Dialogue

This is not an article that ends with outrage or cry for pity. It begins with a demand to talk. Talk about what you know, what you don't know, what you assumed, what you feared.

Ask questions. Listen. Most of all, open up conversations where they’ve long been shut down. Start with yourself, your family, your friends, your circle. If we are to protect the next generation of girls, we must be willing to challenge what we once thought untouchable.

To policymakers, this is your moment to lead with courage. To religious leaders, this is your moment to protect with wisdom. To communities, this is your moment to listen with empathy.

We cannot fight what we refuse to name. So, this is where we start. Not with blame, but with honesty.

Because no girl should have to carry pain wrapped in tradition, and no nation should hide harm in the name of harmony.