Pomparippu, in the northwest, presents a particularly intriguing site. The urn burials, found alongside iron daggers and carnelian beads, resemble those of the South Indian Iron Age, a sign of sustained cross-strait interaction

Pomparippu, in the northwest, presents a particularly intriguing site. The urn burials, found alongside iron daggers and carnelian beads, resemble those of the South Indian Iron Age, a sign of sustained cross-strait interaction

Introduction: Before the Chronicle Begins

Introduction: Before the Chronicle Begins

When the Mahāvaṃsa opens its tale with the arrival of Vijaya in Tambapanni, the narrative does not merely begin; it overwrites. The island becomes a stage awaiting the hero. Yet that stage was already inhabited, by people whose names drift between the historical and the legendary: the Veddas, the Yakkhas, the Nagas. These groups, sometimes referred to as forest dwellers or supernatural antagonists, have long occupied an uneasy place in Sri Lanka’s imagination. They are acknowledged in myth and in folklore but rarely granted the dignity of history.

To understand these groups, ethnographically, archaeologically, and historiographically is to restore a layered prehistory often excluded from Sinhala-Buddhist state narratives. Their presence complicates the idea of a single civilisational origin. Their traces, preserved in oral tradition, megalithic burial sites, serpent cults, and ritual landscapes, offer a counterpoint to the centralising gaze of the chronicles. What follows is not a reconstruction of a singular “first people,” but a map of plural presences.

Yakkhas and Nagas in Text and Terrain

Yakkhas and Nagas in Text and Terrain

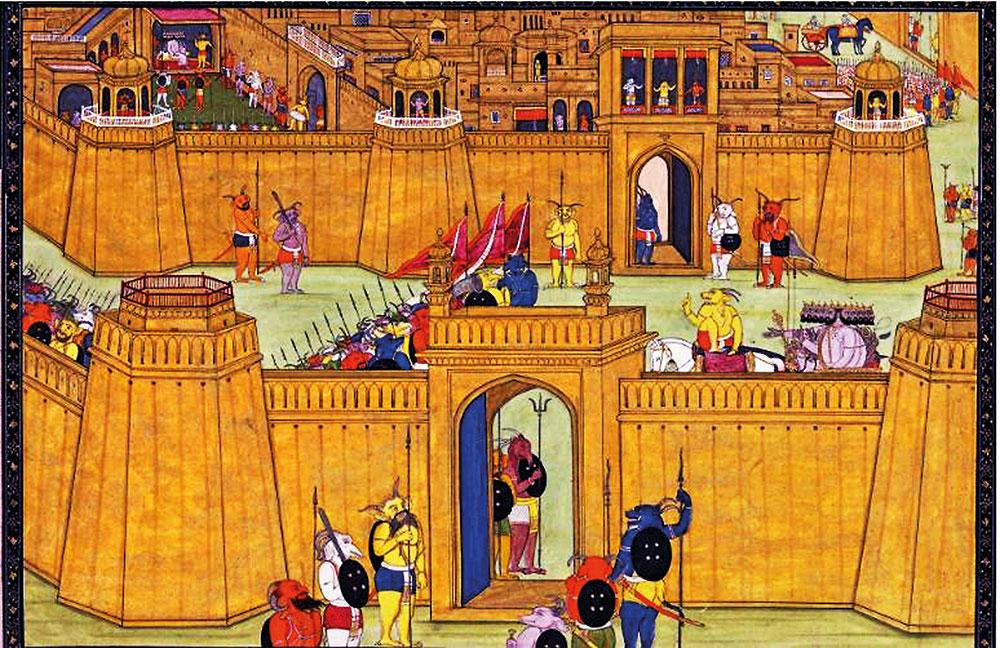

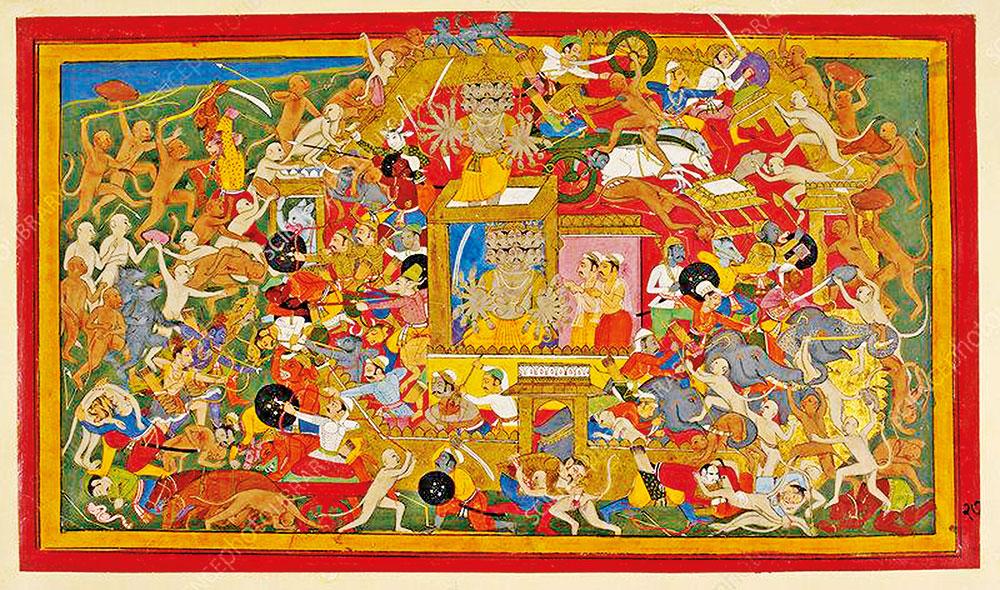

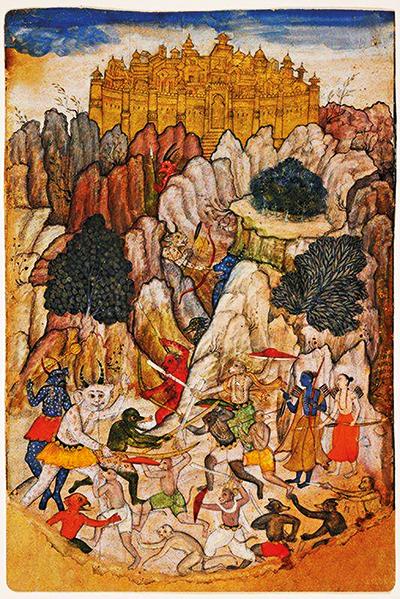

In the Mahāvaṃsa and Dīpavaṃsa, the Yakkhas appear at the threshold of Sinhala history. They are the first to greet Vijaya, not with diplomacy but with ambiguity. Kuveni, the Yakkha queen, is described as both a sorceress and a consort. Her betrayal and eventual death in the forest, abandoned by Vijaya and rejected by her kin, is rendered as a necessary sacrifice for the founding of Sinhala kingship.

Scholars such as W. Malalasekera and A.L. Basham have long observed the parallels between Yakkhas and early non-Brahmanical forest tribes in the subcontinent. Leslie Gunawardana, in his study of state formation in ancient Sri Lanka, notes that the Yakkhas were likely ritual specialists or tribal groups who controlled key territories and trade routes, especially in the hill country. Rather than demons, they may have been the ritual sovereigns of the uplands.

The Nagas, in contrast, are depicted with greater respect. In the Mahāvaṃsa, the Buddha visits Nāgadīpa to mediate a dispute between Naga kings over a jewel-encrusted throne. This episode, while allegorical, encodes a political reality. The Naga polities, possibly linked to serpent-worshipping coastal communities, maintained structured governance and diplomatic ties. Locations such as Kantharodai and Nainativu preserve archaeological evidence of megalithic burials, early trade, and Buddhist influence.

P.E. Pieris, writing in the early twentieth century, remarked on the stylistic parallels between Naga iconography in Sri Lanka and that of South Indian cults, particularly those around Nagapattinam. K. Indrapala has further argued that the Naga identity, while mythologised in later sources, was likely a composite of seafaring merchant clans, ritual leaders, and early Dravidian-speaking groups.

The Veddas: Between Ethnography and Survival

The Veddas: Between Ethnography and Survival

Unlike the Yakkhas and Nagas, who linger largely in the textual past, the Veddas survive in the margins of Sri Lanka’s present. Traditionally residing in the forests of the Uva and North Central Provinces, the Veddas have long been represented as relics of a bygone age. Early colonial ethnographers such as Hugh Nevill, T.H. Parkin, and the Sarasin Brothers saw them as remnants of a pre-Aryan population, describing them in anthropometric terms and reducing their identity to a mixture of physical traits, hunting practices, and supposed linguistic primitivism.

This portrayal, shaped by the racial science of the 19th century, had enduring consequences. It denied the Veddas historical agency, casting them instead as static figures caught outside time. More recent scholars, including Gananath Obeyesekere and Nira Wickramasinghe, have challenged this image. Obeyesekere, in particular, has noted the extent to which Vedda identity is fluid—defined not only by kinship but by economic necessity, social alliance, and ritual practice.

Today, communities like Dambana, Henanigala, and Rathugala offer a complex picture. Many self-identifying Veddas are Sinhala-speaking, and intermarriage with Sinhalese and Tamil villagers is common. Nevertheless, elements of distinctive religious and social practice endure ancestor veneration (nae yaku), forest-based rituals, and oral genealogies that do not trace back to Vijaya but to spirits of hill and grove.

Samanga Amarasinghe’s recent research (2022) repositions the Veddas not as survivors of a forgotten race, but as active participants in a negotiated premodern pluralism. Their marginalisation, he argues, is a result of state formation, land dispossession, and nationalist historiography, rather than a lack of cultural or political presence.

Archaeological Continuity: Megaliths and Migration

Archaeological Continuity: Megaliths and Migration

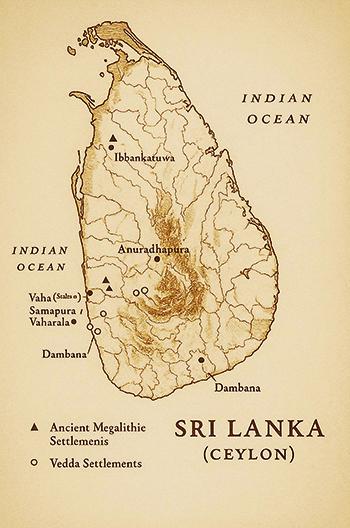

The material record confirms what the textual and oral sources suggest: Sri Lanka’s early society was neither monolithic nor suddenly Aryanised by Vijaya’s arrival. At sites such as Ibbankatuwa, Pomparippu, and the lower strata of Anuradhapura, archaeologists have uncovered burial chambers, urn fields, iron tools, and ceramic assemblages dating back to the first millennium BCE.

The material record confirms what the textual and oral sources suggest: Sri Lanka’s early society was neither monolithic nor suddenly Aryanised by Vijaya’s arrival. At sites such as Ibbankatuwa, Pomparippu, and the lower strata of Anuradhapura, archaeologists have uncovered burial chambers, urn fields, iron tools, and ceramic assemblages dating back to the first millennium BCE.

Siran Deraniyagala, in his extensive excavation reports from the 1980s to early 2000s, proposed a cultural sequence in which megalithic and protohistoric layers gradually gave way to more centralised urban forms, especially with the rise of Anuradhapura as a political centre. Yet even in these early periods, there is clear continuity of religious practice, metallurgy, and interregional trade.

Pomparippu, in the northwest, presents a particularly intriguing site. The urn burials, found alongside iron daggers and carnelian beads, resemble those of the South Indian Iron Age, a sign of sustained cross-strait interaction. But equally important is the localised variation: these were not mere Tamil migrants or Indo-Aryan settlers, but hybridised communities adapting global forms to island life.

These findings challenge the notion of a civilisational rupture. The story of Vijaya may narrate a beginning, but archaeology narrates transformation, not replacement.

Political Mythology and the Erasure of Multiplicity

Political Mythology and the Erasure of Multiplicity

Why, then, has Sri Lanka’s historiography clung so tightly to the Vijayan myth? The answer lies in the politics of nation-making.

Michel-Rolph Trouillot, in Silencing the Past, argued that historical narratives are not merely shaped by facts, but by power over narrative—what gets remembered, by whom, and for what purpose. Similarly, Benedict Anderson, in Imagined Communities, suggested that modern nations rely on invented traditions to forge common identity. Sri Lanka is no exception.

The Mahāvaṃsa emerged during the reign of Mahānāma, at a time when the Anuradhapura kingdom sought to consolidate Buddhist legitimacy against both Tamil incursions and internal heterodoxy. By crafting a singular, sanctified origin story, anchored in Vijaya’s lineage and the Buddha’s prophecy, the chroniclers created a genealogy of righteousness. Everything outside that genealogy became shadow: Yakkhas, Nagas, Veddas.

This logic extended into the colonial and post-colonial periods. School textbooks, government propaganda, and even tourist brochures reproduced the vision of a Buddhist Sinhala civilisational arc, from Vijaya to Dutugemunu to independence. The pre-Vijayan world was reduced to allegory, or else disappeared.

Conclusion: History as Layered Listening

Conclusion: History as Layered Listening

To recover the histories of the Veddas, Yakkhas, and Nagas is not to invent a new national myth. It is to decentralise the old one. These figures, once gods, once queens, once rivals, were not footnotes to the state. They were its foundation.

The rituals of the forest, the serpent shrines by the coast, the chants of Vedda elders, these are not fragments of folklore. They are alternative archives, demanding a method of listening that goes beyond chronicle and stone.

Sri Lanka’s history is not a ladder, ascending from tribalism to kingship to modernity. It is a field of overlapping lives, each with its own temporality, each deserving to be named. In that naming, there is dignity. And in dignity, a more truthful past.