Colombo is often described in headlines and statistics. A financial hub. A city in recovery. A coastline of commerce and contradiction. But cities are not built only of policy or crisis. They are built of glances, gestures, and fleeting intersections of light and shadow. They are built of people who wait at railway crossings, who lean against buses at dusk, who carry entire histories in the way they stand. Nazly Ahmed has made it his quiet life’s work to notice them. Though many recognise his images of Colombo, particularly through the celebrated photobook Colours of Colombo, his practice extends beyond any single city. What draws him is not geography but behaviour. Movement. The choreography of everyday life in public space. Railway platforms. Crossings. Streets where strangers pass within inches of each other without ever meeting eyes. He gravitates toward transit points, places where lives intersect briefly before dispersing again.

There is something almost anthropological in this attention, but without detachment. His images do not study people from a distance. They sit within the same air. They share the same dust, the same humidity, the same fading sunlight. What emerges from this balance is an archive that feels both intimate and expansive. His photographs document not only streets and skylines, but the emotional temperature of a place in time. Economic shifts, social transitions, collective anxieties, and small joys all seep subtly into the background. The city changes. The light changes. People adapt. And through it all, he continues to look.

To interview Nazly Ahmed is not merely to speak to a photographer. It is to speak to someone who has committed himself to attention in an era of distraction. In the end, his work asks a deceptively simple question. If we slowed down, even briefly, what would we notice? And what would that noticing change about the way we move through the world?

1. You have spent decades building digital systems and platforms, yet your photography feels instinctive and deeply human. Do you experience these two worlds, code and candid street life, as separate identities, or are they somehow connected in your mind?

I had not really thought about it this way, but now that you ask, I do not think I consciously treat them as separate identities. Technology has been my professional world for the longest time. Web systems and digital platforms are still my day job. In fact, it was probably my background in tech that first drew me to photography. I was fascinated by the technicalities in photography, understanding light, camera settings, camera gear, and the mechanics behind creating a photograph.

But the more photographs I took, the more I felt a hunger to tell stories rather than just capture technically sound photos. That shift slowly shaped a new identity in me, the one that I carry right now as a street photographer. I never wanted photography to become a full-time profession, and perhaps that decision unintentionally kept the two worlds slightly apart. I had this constant fear that turning it into work might take away the freedom and satisfaction I get when I photograph purely on my own terms.

2. You have said photography is a kind of detox for you. What does it cleanse? Is it the noise of the digital world, the weight of responsibility, or something more personal?

It is really a combination of everything. Working in tech means constant screen time, structured logic, and solving problems within defined systems. After a while, that rhythm can feel heavy. Stepping into the streets with a camera shifts everything. It serves as my escape from the routine of my day job.

3. Street photography depends on anticipation. When you are standing at a railway platform or waiting near a busy junction, what is going through your mind? Are you searching for something specific, or are you waiting to be surprised?

It depends, but for most of the time, I am not searching for something specific. It is more about being alert than being intentional. I observe, and then I begin to notice the expressions and small interactions that most people might overlook. There is anticipation, but I am never quite sure what to expect. I may sense that something is about to unfold, a train arriving or someone stepping into a beam of light, but the exact moment is never predictable. I wait, I watch, and sometimes I am rewarded with something I could not have planned. That unpredictability is what keeps me coming back. There are far more disappointments than successful moments, and I have learned to accept that as part of the process.

4. Your Independence Day photograph featuring the Union Jack on a car roof sparked conversation. When you press the shutter, are you thinking politically, historically, symbolically, or purely visually?

In that particular photo, to be honest, I could not have predicted any of that to even think on those lines. I was waiting to capture the photos of the Independence Day parade when I saw a Mini with the Union Jack driving around. I have a soft spot for Minis and instinctively started clicking it as I would usually do. Everything that unfolded after was totally unpredictable. That is the beauty of this genre. There are times I would plan so much to shoot something based on a narrative and hope things would happen the way you want, but you end up with nothing, while it can happen the other way around as in this instance.

5. In Colours of Colombo, the city feels less like a backdrop and more like a living character. How would you describe Colombo if it were a person?

If Colombo were a person, it would be diverse, culturally rich, and delightfully chaotic, unpredictable yet quietly supportive. Its beauty is not obvious at first. You only notice it when you pause, observe, and truly listen to its rhythm.

6. Much of your work captures motion, trains, planes, fleeting glances. Is that a reflection of the city’s restlessness, or your own?

I love capturing trains, planes, or even supercars simply because I am still a kid at heart. Isn’t that true for most of us? With photography, that kid just got wings. While my focus now is on street photography, I try to balance motion with human stories, especially at railway stations where you encounter endless interactions and narratives. Being a commuter myself for many years has made me comfortable in these spaces, letting me quietly observe and capture the city’s rhythm through its people.

7. You began photography without access to a camera in your early years. Do you think that distance, wanting something you could not immediately have, shaped how seriously you now approach the craft?

I do sometimes wish I had started photography much earlier, but I am grateful for what I have been able to achieve with the limited resources I had, especially since I have never pursued it full-time to own expensive gear. I would not call myself a professional. I prefer to focus on a defined space that I have carved out for myself. Staying within that space gives me the most satisfaction, and it is where I feel I can create work that truly resonates with me.

8. The extended edition of Colours of Colombo arrives at a time when Sri Lanka has endured profound economic and social shifts. Did the tone of your photography change in response to these realities?

Naturally, the context around me seeps into my work. Colours of Colombo has always been about capturing the city’s everyday life, its energy, quirks, and the stories of its people. As the city faced economic and social shifts, I became more attentive to resilience and small moments of hope amid uncertainty. The tone became more aware, highlighting how life continues, adapts, and still finds colour even in challenging times.

9. What does ethical street photography mean to you?

To me, ethical street photography means observing and capturing life without exploiting or intruding on people’s dignity. It is about respect. Respecting the subjects, their privacy, and the context in which they exist, while still telling honest stories, letting the moments speak for themselves. While street photography norms generally do not require asking permission to photograph people in public spaces, I try to do so whenever the situation allows. I have always made it a point to show people in their best form, rather than in their worst moments.

10. When you look at your archive years from now, what do you hope it will say about this specific moment in Colombo’s history?

Years from now, I hope my archive will show Colombo as a city of colour, culture, and everyday poetry. I want it to preserve the small gestures, fleeting moments, and quiet human interactions that reveal how life moves on, how people adapt, laugh, and continue to find beauty in the ordinary. More than anything, I hope it tells the story of a vibrant, restless, and deeply human city, reflecting the enduring spirit of its people.

11. One of my two favourites is Ignorance is Bliss… Until It Is Too Late. I could honestly write pages about how layered and loaded that image feels. My other is Colombo’s Golden Hour, a masterpiece that never fails to calm me. I would love to hear your thoughts on these two pieces and what they mean to you.

Colombo’s Golden Hour

Colombo is nothing short of beautiful sunsets, and though it might be cliché, I am a constant chaser of these glorious sunsets. I love shooting silhouettes using the backlit sun to my advantage. I found this great spot near the crossing line and I shot it at a lower angle. While being there, I shot for quite some time, and one of the best shots out of the lot was this one. For me, it is a classic Colombo moment, always in transit, always connected, yet often lost in individual worlds.

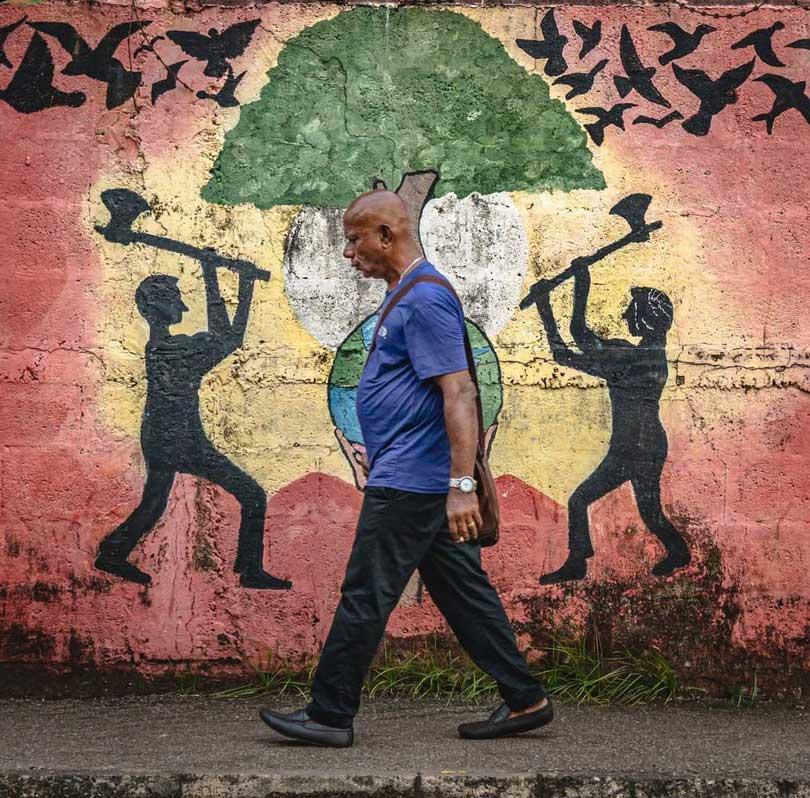

Ignorance is Bliss… Until It Is Too Late

I had seen this mural highlighting the need to protect the environment, and this particular section caught my eye. I felt it would make a compelling photograph if I could place a subject in the middle, reflecting how ordinary individuals carry the weight of larger narratives, often without realizing it. The mural speaks of collective responsibility and environmental protection, yet everyday life continues as usual in front of it. In a subtle way, it also hints at the consequences of neglect, that by harming the environment, we ultimately harm ourselves. Moments like this remind me that the city’s biggest stories are often unfolding quietly, in plain sight.