For as long as she has held public office, Dr. Harini Amarasuriya has been subjected to a level of hostility that goes far beyond the boundaries of legitimate democratic critique. Her work, her leadership, and her authority have repeatedly been met not simply with disagreement, but with misogynistic hostility that seeks to undermine her credibility as a woman in power. The most recent wave of attacks, triggered by a misprint in a Grade 6 English language module, has once again revealed how quickly public discourse can slide from accountability into gendered abuse.

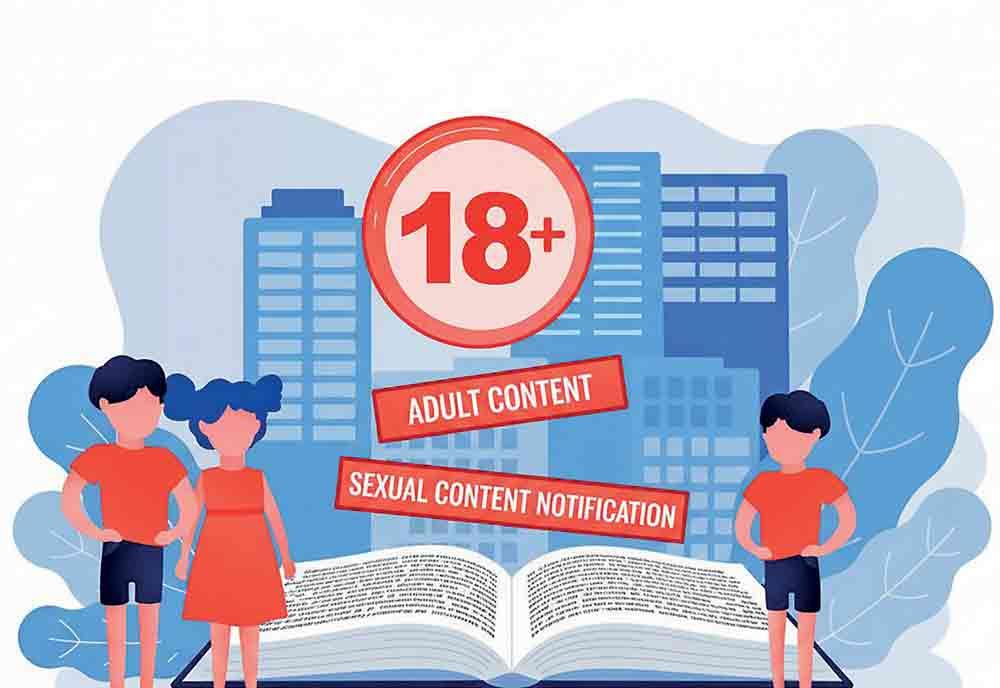

The error itself is not in dispute. A website name considered age inappropriate was mistakenly included in an educational resource. This is a serious matter. Children’s wellbeing must always be paramount, and educational materials demand rigorous standards of review and quality control. Transparency, internal investigation, and institutional accountability are not optional. They are fundamental to public trust in the education system. However, what followed was not a measured or principled demand for accountability. Instead, the incident became the pretext for a barrage of sexualised attacks against the Prime Minister, shifting the focus away from systemic responsibility and towards personal vilification.

This pattern is not new. When women occupy positions of authority, mistakes are rarely treated as organisational failures. Instead, they are personalised, moralised, and weaponised. The discussion moves away from procedures and safeguards and becomes an indictment of the woman herself. In this case, a printing error escalated into a sustained campaign of character assassination, with sexualised language and insinuation deployed to erode the Prime Minister’s legitimacy. This is not about education policy. It is about disciplining women who dare to lead.

Sexualised harassment is not political critique. It does not strengthen democracy or improve governance. It serves one purpose only; to intimidate, humiliate, and silence. By reducing a woman leader to her body or by attacking her dignity rather than her decisions, such abuse seeks to push women out of public life altogether. The fact that these attacks were amplified by certain political actors and digital and social media channels illustrates how deeply embedded misogyny remains within political culture.

The double standards imposed on women politicians are glaring. Male leaders are criticised for their policies and performance. Women leaders are subjected to scrutiny of their character, morality, and personal lives. Where men are afforded the presumption of competence, women are treated as perpetual suspects whose authority must constantly be justified. This imbalance is not accidental. It is a structural feature of patriarchal politics designed to keep power male dominated.

What makes the current moment particularly concerning is the ease with which public outrage was mobilised into a spectacle of abuse. Instead of demanding better institutional safeguards, many chose to target the Prime Minister herself, portraying her as personally culpable and deserving of public humiliation. This tactic diverts attention from the real issues at stake and replaces democratic accountability with punitive misogyny.

We must name this phenomenon for what it is. These attacks constitute gender based political violence. They are deliberate acts intended to weaken women’s participation in politics through fear and degradation. Political violence does not always take the form of physical harm.

It also operates through sustained harassment, threats, and reputational damage that make it unsafe for women to remain in public life. Such violence sends a clear message to all women; power comes at a personal cost that men are rarely asked to pay.

This is an assault not only on an individual leader, but on democracy itself. A political system that allows women to be targeted with impunity for holding office cannot credibly claim to be representative or inclusive. When women are punished for leading, democratic participation becomes conditional and unequal. The loss is not only borne by women politicians, but by society as a whole, which is deprived of diverse leadership and perspectives.

As women, we need to stand in full solidarity with Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya and with all women political representatives who have faced similar attacks. They hold office by democratic mandate. Their authority is legitimate. Their leadership is earned. They are not exceptions to the rule, nor are they intruders in public life. They have every right to participate in politics free from intimidation, harassment, and abuse.

These attacks also raise serious legal and ethical concerns. Sri Lanka is bound by international obligations to ensure equality and non-discrimination in political and public life. Under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, the State is required to take active measures to eliminate discrimination and violence against women in political spaces. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights guarantees the right to participate in public affairs without coercion or intimidation. Gender based political violence is incompatible with these commitments.

Accountability must never be confused with abuse. Public officials must answer for errors, but scrutiny must be proportionate, evidence based, and directed at systems and decisions, not at personal dignity. When accountability is weaponised to justify misogyny, it ceases to serve democratic ends. It becomes a tool of exclusion rather than reform.

The responsibility to address this crisis is collective. The Government of Sri Lanka must take concrete steps to prevent, investigate, and punish acts of gender based political violence, whether they occur online or offline. Legal frameworks must be enforced, and gaps in protection must be addressed with urgency. Political parties across the spectrum have a duty to publicly condemn misogynistic attacks and to defend women representatives, regardless of political alignment. Silence in the face of abuse is not neutrality. It is complicity.

Digital platforms, too, must act decisively. Online harassment is not an inevitable by-product of free expression. Platforms have the capacity and the obligation to curb coordinated abuse, remove harmful content, and prevent the normalisation of misogyny. Failure to do so creates an environment in which political violence thrives unchecked.

At stake is the future of women’s political participation in Sri Lanka. If such attacks are allowed to continue without consequence, they will achieve their intended effect. Women will think twice before contesting elections, accepting appointments, or speaking openly in public life. Democracy will become narrower, poorer, and less representative.

Democracy cannot be defended while women are punished for leading. Protecting women’s political participation is not optional. It is a democratic imperative. A political culture that tolerates sexualised attacks against women in power undermines the rule of law, equality, and the very idea of representative governance.

We must reject the double standards that continue to govern how women in politics are judged and treated. We must condemn the cynical exploitation of public outrage as a means of justifying misogynistic abuse. We must refuse to accept a political culture in which violence, humiliation, and intimidation are presented as an inevitable cost of women’s leadership. We must continue to speak out, organise collectively, and demand accountability until women are able to exercise political power free from fear and degradation, until leadership is assessed by competence and integrity rather than gender, and until democracy in Sri Lanka genuinely belongs to all.