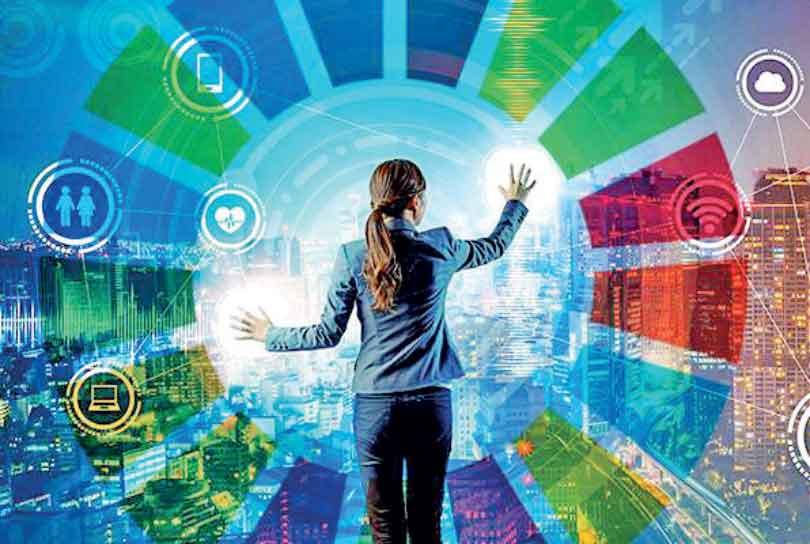

For nearly two decades, Sri Lanka’s information technology (IT) sector has been promoted as a cornerstone of economic diversification, foreign exchange generation, and youth employment. From a modest export base in the early 2000s, the industry expanded rapidly, benefiting from global demand for offshore services, a relatively well-educated workforce, and competitive labour costs. By the late 2010s, IT and business process management (IT-BPM) services were generating an estimated USD 1.3–1.5 billion in annual export revenue and employing approximately 170,000–175,000 professionals. The sector emerged as one of the country’s largest service export earners and a symbol of Sri Lanka’s potential to move up the value chain.

For nearly two decades, Sri Lanka’s information technology (IT) sector has been promoted as a cornerstone of economic diversification, foreign exchange generation, and youth employment. From a modest export base in the early 2000s, the industry expanded rapidly, benefiting from global demand for offshore services, a relatively well-educated workforce, and competitive labour costs. By the late 2010s, IT and business process management (IT-BPM) services were generating an estimated USD 1.3–1.5 billion in annual export revenue and employing approximately 170,000–175,000 professionals. The sector emerged as one of the country’s largest service export earners and a symbol of Sri Lanka’s potential to move up the value chain.

Yet despite these impressive headline figures, a growing chorus of professionals, educators, employers, and even recent graduates now question whether the sector is facing a deeper structural crisis. While the industry has not collapsed, there is a widening gap between perception and reality. On paper, the numbers still look healthy. On the ground, however, many indicators point to strain, imbalance, and a loss of momentum that cannot be ignored.

At a surface level, official data continues to offer reassurance. ICT services contribute close to 9 percent of Sri Lanka’s total services exports, while the broader digital economy is valued at roughly Rs. 1.3 trillion, accounting for around 4–5 percent of GDP. Government policy documents remain optimistic, projecting ambitious targets such as USD 5 billion in IT exports and the creation of 200,000 new jobs by 2030. These goals reflect a belief that IT can remain a pillar of economic recovery and long-term growth, especially in a country seeking to reduce reliance on traditional exports.

Beneath this optimism, however, lies a more complex and troubling reality. One of the most pressing concerns is the growing mismatch between education outcomes and industry requirements. Over the past decade, IT became synonymous with high salaries, flexible work environments, and overseas opportunities. Predictably, student demand surged. In response, both public universities and private institutions expanded their intakes, while numerous new private campuses entered the market offering IT-related degrees and diplomas.

While this expansion widened access to higher education, quality assurance struggled to keep pace. Industry professionals increasingly report that a significant proportion of graduates lack even basic programming, analytical, and problem-solving skills, despite holding recognised qualifications. This concern is not merely anecdotal. Sri Lanka produces thousands of IT and computer science graduates annually, yet entry-level recruitment has become more competitive than ever. Employers often describe recruitment processes that involve filtering hundreds of applications to identify a handful of candidates who meet minimum technical standards.

Many companies now invest substantial time and resources in screening, testing, and retraining new hires, only to find that a large share of graduates struggle with fundamental concepts such as algorithms, data structures, version control, or logical reasoning. The growing dependence on artificial intelligence tools in academic assessments has further intensified this problem.

While AI can be a valuable learning aid, its unchecked use has enabled some students to complete assignments and even final-year projects without developing genuine coding ability or conceptual understanding. The result is a growing pool of degree holders who are academically certified but industry unready.

Compounding these challenges is the loss of experienced professionals through emigration. Since the economic crisis of 2022, Sri Lanka has witnessed a sustained outflow of skilled workers, particularly in high-demand sectors such as IT. Senior engineers, solution architects, technical leads, and product managers individuals critical for mentoring junior staff, maintaining engineering standards, and managing complex client relationships have left in search of better remuneration, currency stability, and quality of life abroad.

Their departure has created a leadership and experience vacuum within many organisations. Companies are increasingly forced to operate with fewer mentors, compressed hierarchies, and thinner layers of technical oversight. In some cases, relatively inexperienced staff are promoted into roles beyond their capacity, not because they are ready, but because there are no alternatives. While this may keep projects moving in the short term, it raises serious concerns about long-term quality, sustainability, and reputational risk.

At the same time, Sri Lanka’s IT sector is being reshaped by broader global technological and market shifts. Worldwide, the industry is experiencing slower growth, reduced hiring, and longer recruitment cycles. Clients are more cautious with spending, and companies are under pressure to deliver more with less. Automation and AI-assisted development tools have enabled smaller teams to achieve productivity levels that previously required much larger workforces.

For offshore destinations like Sri Lanka, this shift has had mixed consequences. While demand remains for high-quality engineering and specialised services, the market for routine development, testing, and support work has shrunk. Clients increasingly expect higher value, deeper domain knowledge, and innovation, rather than sheer manpower. As a result, entry-level and mid-level roles the traditional gateway for young professionals are becoming scarcer, making it harder for new graduates to gain industry experience.

Policy and economic conditions have also played a role in shaping current challenges. The imposition of indirect taxes on digital services, software subscriptions, and cloud platforms has increased operational costs for IT firms that depend heavily on global tools and infrastructure. While fiscal consolidation is unavoidable given Sri Lanka’s economic realities, industry stakeholders argue that insufficient consultation and poorly calibrated policies have weakened competitiveness at a time when the country must attract, not deter, global clients.

Moreover, recent national accounts data showing contraction in parts of the computer services segment underscore the sector’s vulnerability to currency volatility, global demand fluctuations, and external shocks. Unlike traditional exports, IT services rely on trust, reputation, and long-term relationships. Once lost, these are difficult to rebuild.

Taken together, these factors help explain why many within the industry perceive a “downfall,” even as macro-level indicators suggest resilience. In reality, Sri Lanka’s IT sector is not collapsing; it is undergoing a painful and necessary correction. The era in which an IT degree alone guaranteed employment is over. What remains is a more demanding environment that rewards depth over volume, skill over certification, and long-term capability over short-term expansion.

The challenge for policymakers, educators, and industry leaders is therefore clear. Without decisive reforms particularly in higher education quality, curriculum relevance, industry-academia collaboration, talent retention strategies, and coherent policy support the sector risks stagnation. Expanding enrolments without improving outcomes will only worsen underemployment and frustration among graduates. Ignoring the loss of senior talent will erode institutional knowledge and weaken global competitiveness.

Conversely, if these weaknesses are addressed, IT can continue to be a pillar of Sri Lanka’s recovery and long-term growth. This will require difficult choices: prioritising quality over quantity in education, investing in faculty development, aligning incentives to retain experienced professionals, and crafting policies that recognise the strategic importance of digital exports.

What is unfolding today should not be viewed merely as decline, but as a warning. Growth without quality is unsustainable. How Sri Lanka responds in the coming years will determine whether its IT industry regains momentum and evolves into a high-value global player or gradually loses its competitive edge in an increasingly unforgiving international market.