Violence against women and children remains one of South Asia’s most persistent and devastating human rights violations. Despite growing awareness, legal reforms, and grassroots activism, 2025 has seen a troubling rise in reported incidents, from sexual assaults and trafficking to femicide and state-enabled repression. Socioeconomic instability, patriarchal norms, weak legal enforcement, and climate-induced pressures have compounded the crisis. Recent cases from India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan underscore both the depth of the problem and the urgent need for systemic change.

A Region Under Strain: Prevalence of Gender-Based Violence

According to the World Health Organization, South Asia continues to report some of the highest rates of gender-based violence (GBV) globally. In 2025, the UN Spotlight Initiative emphasized that nearly one in two women in some South Asian countries has experienced physical or sexual violence, predominantly from intimate partners. India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka, despite differing political systems, share structural drivers: patriarchal traditions, underfunded justice systems, and insufficient protections for survivors.

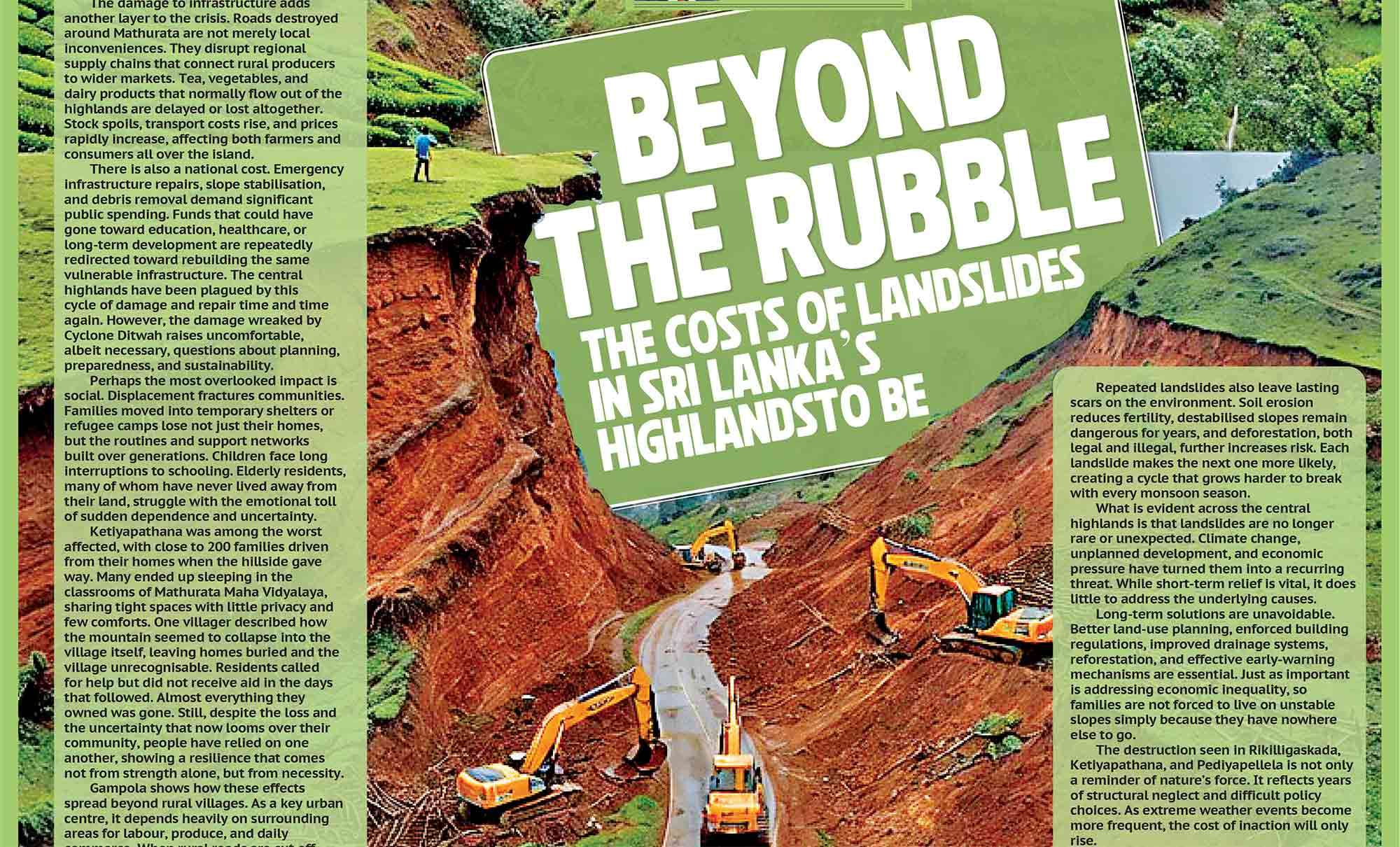

Climate Change as a Risk Multiplier

Recent studies, including a UN Women report published in early 2025, warn that rising climate-related displacement is disproportionately affecting women and girls. Natural disasters increase GBV risks, particularly in informal camps and resettlement areas where security is scarce and reporting mechanisms are virtually non-existent. For instance, following Cyclone Remal in May 2025, aid groups in Bangladesh’s coastal districts reported a surge in forced marriages of adolescent girls, a survival strategy for impoverished families.

Shocking 2025 Cases: Tragedies Across BordersBangladesh: Magura Child Rape and Murder

In March 2025, the rape and death of an eight-year-old girl in Magura district shocked Bangladesh. The accused, a relative, was arrested and confessed during preliminary interrogation. The government, under intense public pressure, pledged expedited legal proceedings. The judiciary has been instructed to resolve child abuse cases within six months.

Sri Lanka: The Suicide of Dilshi Amshika

The tragic suicide of 15-year-old Dilshi Amshika in April 2025 drew national outrage. She had previously reported being sexually abused by a teacher in 2024. Activists accused education officials of failing to act on her complaint, effectively pushing her to the brink. Following public protests, the Sri Lankan Ministry of Education suspended the accused teacher, and the National Child Protection Authority launched a formal investigation. The case has intensified calls to integrate mental health support and safe reporting channels into school systems.

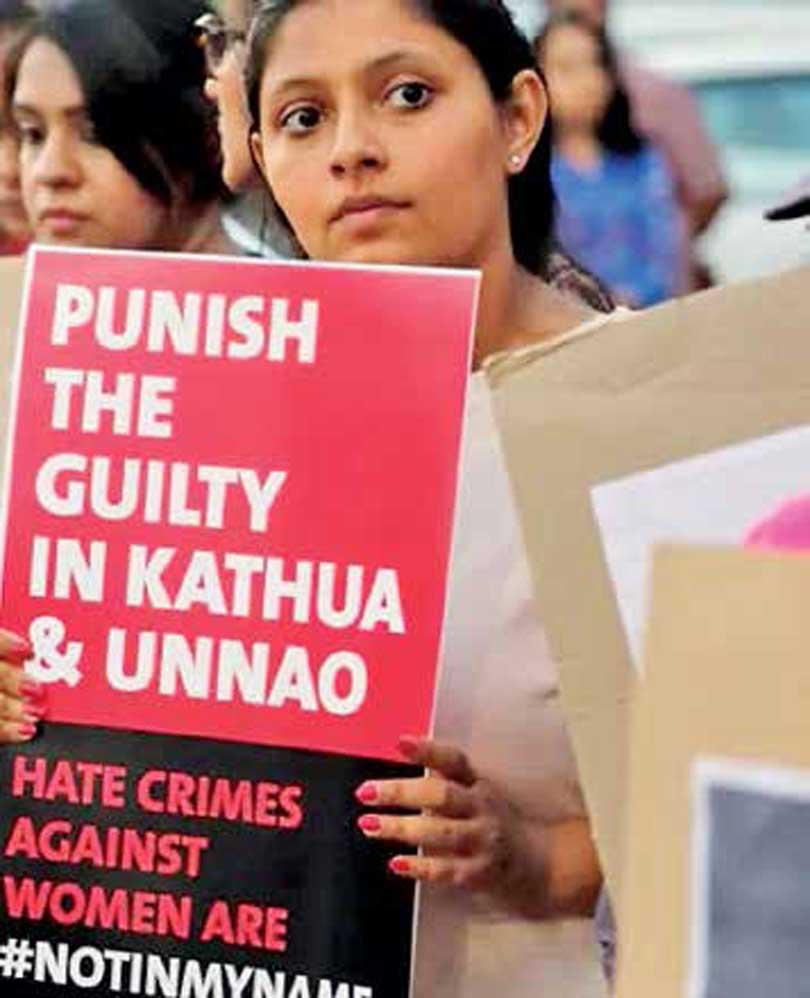

India: Rape and Trafficking in 2025 Nainital Assault Case

In April 2025, a 73-year-old man in Nainital, Uttarakhand, was arrested for allegedly assaulting a 12-year-old girl. Police faced criticism over delayed action. The suspect was charged under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act (+POCSO) and remains in custody.

Nagpur Child Trafficking Ring

In another disturbing case, a minor girl kidnapped from Nagpur was rescued after being sold into marriage for INR 250,000. Authorities arrested the alleged kingpin, a woman named Roma Patil, who is believed to be part of a larger trafficking network spanning Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh.

Rajasthan: Two Minors Raped in Separate Incidents

In August 2025, two separate rape cases involving a 6-year-old and a 7-year-old girl in Rajasthan drew widespread public anger. The accused in both cases were known to the victims, exposing systemic failures in family and community safeguards. Chief Minister Bhajan Lal Sharma announced that fast-track courts would handle these cases, with dedicated medical and psychological support for the victims.

Mumbai Newborn Trafficking

In July 2025, Mumbai police rescued a six-day-old baby girl who was being sold for INR 550,000. The child’s biological parents, along with three other suspects, were arrested. Investigators believe this case is part of a newborn trafficking racket targeting vulnerable families.

Pakistan: Murder of Sana Yousaf

17-year-old influencer Sana Yousaf, known for her advocacy on girls' education and cultural identity, was shot dead in her Islamabad home in June 2025. Her killing led to protests across Pakistan, with women’s rights groups like Aurat March demanding transparency and a full investigation. Authorities have not ruled out a targeted killing related to her activism. Human rights observers call Sana’s murder a reminder of how digital visibility makes outspoken women vulnerable to offline violence.

Afghanistan: Legalized Oppression of Women

Since returning to power in 2021, the Taliban has institutionalized gender apartheid, and 2025 marks further deterioration. According to a recent UN report, women in Afghanistan are now completely excluded from formal justice systems. With no access to education, employment, or public life, Afghan women rely on male-dominated informal councils that often perpetuate abusive norms. Richard Bennett, UN Special Rapporteur for Afghanistan, warned in March 2025 that the Taliban’s use of so-called ‘justice’ has created a legal regime where violence against women is state-sanctioned and invisible.

State-Sanctioned

Suppression of Activism

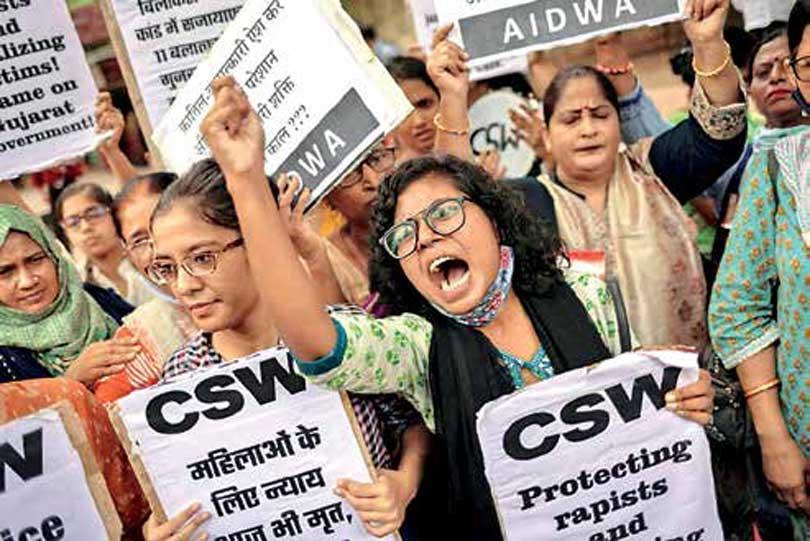

Bangladesh: Weaponizing Sexual Violence in Politics

In 2024–25, multiple human rights reports, including by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, documented cases where women political activists and journalists in Bangladesh were subjected to threats of sexual violence, some reportedly by security personnel. In March 2025, female student activists alleged that rape threats were used to intimidate participants in Dhaka’s campus protests over university autonomy and governance. Civil society organizations are urging the Bangladeshi government to strengthen protections for women in public life.

Institutional ChallengesWeak Law Enforcement

Despite strong laws like India’s POCSO and Bangladesh’s Prevention of Oppression Against Women and Children Act, enforcement remains patchy. Victims and their families often face pressure to withdraw complaints, police delays, or humiliating investigations. In Pakistan, conviction rates for rape remain below 2%, and women often need four male witnesses to substantiate a claim, effectively silencing survivors.

Underreporting and Stigma

Cultural stigma discourages many survivors from reporting crimes. A 2025 UNFPA report found that more than 60% of women in South Asia never report incidents of domestic or sexual violence due to fear of retaliation, social ostracism, or disbelief by authorities.

Policy and Civil

Society Responses

Legal Reforms and Fast-Track Courts

In India and Bangladesh, fast-track courts for sexual violence cases have gained traction in 2025. However, critics argue that they often lack trained prosecutors and gender-sensitive procedures.

UN Spotlight Initiative

The Spotlight Initiative, active in South Asia since 2020, continues to support gender-responsive budgeting, survivor services, and community mobilization. In 2025, it launched a new framework integrating climate adaptation with GBV prevention, particularly in flood-prone regions of Nepal and Bangladesh.

Role of Activism

Grassroots protests following high-profile cases, such as the Dilshi Amshika suicide in Sri Lanka and the Sana Yousaf murder in Pakistan, have reignited feminist organizing. Movements like Aurat March, Girls Not Brides, etc. are campaigning for digital safety, child marriage bans, and better school protections.

The events of 2025 reveal not only the sheer brutality faced by women and children in South Asia but also the inadequacies of current institutional responses. From urban centers to rural provinces, girls and women are caught in cycles of abuse exacerbated by poverty, environmental disasters, and deep-seated cultural norms. But amidst the grief and injustice, resistance is growing. Survivors, journalists, teachers, and activists are working to dismantle impunity and foster systemic change. The future will depend not just on new laws but on the will of governments, communities, and international actors to prioritize gender justice as essential to peace and development in the region.