The real political and cultural reconstitution, however, came under Parakramabahu II, whose reign (c. 1236–1270) has been retrospectively framed by both the Cūḷavaṃsa and modern scholarship as a period of rehabilitation

To cast Dambadeniya as ‘forgotten’ is perhaps less an indictment of modern memory than a reflection of historiographic selectivity. National histories often privilege visibility, ruins that awe, battles that inspire, and reigns that transform.

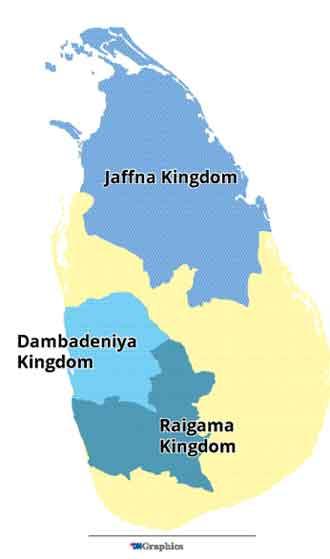

In the historical imagination of Sri Lanka, certain capitals dominate: Anuradhapura for its longevity, Polonnaruwa for its architectural and hydraulic sophistication, and Kandy for its symbolic resistance to colonialism. Yet Dambadeniya, the short-lived 13th-century capital, remains comparatively obscured. Neither monumental nor militarily dominant, it is frequently bypassed in national narratives.

In the historical imagination of Sri Lanka, certain capitals dominate: Anuradhapura for its longevity, Polonnaruwa for its architectural and hydraulic sophistication, and Kandy for its symbolic resistance to colonialism. Yet Dambadeniya, the short-lived 13th-century capital, remains comparatively obscured. Neither monumental nor militarily dominant, it is frequently bypassed in national narratives.

And yet, it was precisely Dambadeniya’s transitional and restorative role that made it indispensable in the preservation of Sinhala-Buddhist statecraft following the fragmentation of Polonnaruwa.

The rise of Dambadeniya occurred during a period of acute political decentralisation. Following the death of Parakramabahu I, Polonnaruwa disintegrated under successive waves of South Indian incursions, dynastic strife, and the erosion of centralised hydraulic agriculture (Liyanagamage, 1963). In response to this instability, Vijayabahu III relocated the political nucleus to Dambadeniya, a fortified hilltop in the Kurunegala district. The site’s topography, elevated, defensible, and removed from the vulnerabilities of the eastern lowlands, reflects a strategic shift from expansive state-building to defensive consolidation (Rathnayake, 2024). The real political and cultural reconstitution, however, came under Parakramabahu II, whose reign (c. 1236–1270) has been retrospectively framed by both the Cūḷavaṃsa and modern scholarship as a period of rehabilitation. Known as Panditha Parakramabahu, he did not merely occupy Dambadeniya; he invested it with ideological capital. His rule signalled a movement from conquest to conservation: a deliberate recentring of kingship around Buddhist orthodoxy, literary production, and symbolic legitimacy.

This was no minor undertaking. The Tooth Relic, a sacral object vital to the idea of kingship, was relocated and ritually enshrined in Dambadeniya, reaffirming the city’s status as the epicentre of legitimate rule (Sudharmawathie, 2021). Meanwhile, Parakramabahu II sponsored the compilation and revision of key Pali texts, including the Dhammapadatthakathā and the authorship of the Kavisilumina, which revitalised the Sinhala literary idiom. Such efforts were not mere expressions of piety or patronage; they were acts of cultural rearmament in the face of geopolitical fragmentation (Gamage & Setunga, 2010).

Dambadeniya’s diplomatic positioning is equally notable. Parakramabahu II pursued a flexible policy of engagement with South Indian polities, especially the Pandya kingdom, utilising both epistolary diplomacy and military action when necessary. These interactions reflect not a diminished polity, but one acutely aware of its diminished material base and acting accordingly (Rathnayake, 2024a). Unlike the centralised imperial ambition of Polonnaruwa, Dambadeniya’s model of governance was pragmatic, locally grounded, and regionally attuned. The material footprint of Dambadeniya is modest and therein lies much of its interpretive neglect.

Absent are the monumental tanks and sprawling monastic complexes of its predecessors. What remains are the outlines of a palace, fragments of inscriptions, and traces of a once-enshrined Tooth Relic. These architectural absences, however, should not be mistaken for political insignificance. Rather, they indicate a kingdom that operated on principles of restoration and custodianship, not expansion or display (Strickland, 2011).

Absent are the monumental tanks and sprawling monastic complexes of its predecessors. What remains are the outlines of a palace, fragments of inscriptions, and traces of a once-enshrined Tooth Relic. These architectural absences, however, should not be mistaken for political insignificance. Rather, they indicate a kingdom that operated on principles of restoration and custodianship, not expansion or display (Strickland, 2011).

Indeed, Dambadeniya’s very ephemerality offers a lens through which to reconsider the nature of capital formation in medieval Sri Lanka. Its importance lies not in its physical legacy, but in its institutional continuity, its ability to bridge the collapse of the hydraulic civilisation with the gradual emergence of smaller, regional polities such as Yapahuwa, Kurunegala, and eventually Kandy. To cast Dambadeniya as ‘forgotten’ is perhaps less an indictment of modern memory than a reflection of historiographic selectivity. National histories often privilege visibility, ruins that awe, battles that inspire, and reigns that transform. Dambadeniya does none of these. Instead, it sustained. It held the line when the state was fraying. It reaffirmed the relationship between Buddhism and sovereignty when both were in doubt. And in doing so, it provided the connective tissue without which later political revivals would have foundered.

As we continue to explore our past not merely as a sequence of empires but lend individual gravitas to specific periods and communities, Dambadeniya demands recognition, not as a failed capital, but as a crucible of resilience. We often ask: Why do we remember some kingdoms and forget others? Perhaps the answer lies not in what was built, but in what was saved. Dambadeniya saved continuity. It stood against historical erasure. And in doing so, it allowed for the future kingdoms to rise upon a stable, albeit narrow, foundation. To remember Dambadeniya is not just to revisit a hilltop kingdom; it is to acknowledge that history’s true labours often happen in the margins, in periods of quiet recovery. And perhaps therein lies the most valuable lesson: not all historical worth is monumental. Some of it is transitional. Some of it is tender. And some, like Dambadeniya itself, is quietly dignified.