.Violence against women is a global emergency with local fingerprints. It happens in homes and streets, online and in workplaces, in warzones and under the cover of bureaucratic neglect. While the language of harm, assault, coercion, exploitation, sounds familiar everywhere, each country’s history, laws, and social norms shape how specific crimes occur, how often they are reported, and whether justice follows. Below are ten snapshots, one crime pattern in each of ten different countries, meant to illuminate both the diversity of abuses and the shared urgency to end them.

Mexico: Femicide and the Machinery of Impunity

In Mexico, femicide, the killing of women because they are women, has become a stark indicator of gendered violence. The crime is aggravated not only by brutality but by systemic impunity: cases stall, evidence disappears, families are forced to act as investigators, and offenders exploit gaps in policing and prosecution. Urban peripheries and transit corridors can be especially dangerous, but femicide is not confined to one region or class. Murals, marches, and pink crosses have turned public grief into public record, yet many families report years-long battles to have cases even classified accurately. While special femicide statutes exist, they are unevenly applied. Reforms that strengthen evidence handling, protect victims’ families from intimidation, and create specialized investigative units with independent oversight are essential to convert law on paper into safety in practice.

India: Sexual Assault and Dowry-Linked Cruelty

India’s legal code criminalizes rape, marital cruelty, and dowry harassment, yet gendered violence persists across rural and urban settings. Survivors of sexual assault confront social stigma, sluggish trials, and medical and police procedures that can retraumatize. Alongside sexual violence, “dowry deaths” and domestic cruelty tied to financial demands remain a grim pattern: women are beaten, coerced, or killed for failing to meet escalating dowry expectations. Protection laws and fast-track courts exist, but implementation varies widely by state; police training, victim support services, and witness protection are uneven. Community pressure often pushes compromise instead of prosecution. Sustained investment in survivor-centred policing, legal aid, and shelters, paired with public campaigns that reframe dowry as illegal and dishonourable, can help shift both outcomes and culture.

South Africa: Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Offences

South Africa reports some of the highest levels of intimate partner violence globally. The intersecting forces of inequality, alcohol abuse, firearm availability, and historical trauma contribute to rates of assault and homicide against women that are staggering. Protective orders are available but can be undermined by slow enforcement and limited shelter capacity. Sexual offences legislation is robust, yet case attrition, from initial complaint to conviction, remains high. Grassroots networks, including survivor-led organizations and community patrols, often backfill what the state cannot deliver, accompanying women to stations, tracking case numbers, and demanding accountability from local commanders. Scaling these models with state funds, expanding survivor-friendly clinics, and tightening firearm seizure protocols when protection orders are issued are practical levers to reduce harm.

Japan: Voyeurism, “Upskirting,” and Digital Stalking

In a country known for low overall crime, tech-enabled abuse has become a prominent front in Japan’s gendered violence landscape. Hidden cameras in public spaces, “upskirting” on crowded trains, and the sharing of non-consensual images exploit both density and discretion. Anti-voyeurism statutes and platform moderation have improved, but enforcement struggles with the speed and anonymity of digital distribution. Stalking, often an escalation after breakups, can slip past legal thresholds until physical harm occurs. Stronger, clearer prohibitions on image-based abuse, rapid takedown obligations for platforms, and specialized cybercrime units trained in digital forensics are critical. Workplace and school protocols that normalize reporting, and treat image-based violations as serious crimes, not pranks, also help shift norms.

Nigeria: Trafficking, Kidnapping, and Forced Marriage

Nigeria’s vast geography and complex conflicts create overlapping risks: trafficking networks move women and girls across borders for sexual exploitation and domestic servitude; armed groups in the northeast have abducted students and coerced marriages; and in some communities, customary practices can be invoked to justify early or forced unions. The legal framework prohibits trafficking and child marriage, but enforcement is uneven, and victims face intense pressure to “settle” informally. Solutions require cross-border coordination, safe school initiatives, witness protection, and reintegration programs that include education, psychosocial care, and economic support. Local women’s groups are often the first responders; durable progress comes when they are resourced and integrated into national strategies.

France: Intimate Partner Homicide and the System’s Blind Spots

France has faced public reckoning over intimate partner homicides, which persist despite protective measures. Women often report long trails of documented threats: police calls, hospital visits, restraining order attempts. Yet risk assessment can be fragmented, with data in separate silos and limited real-time coordination between police, prosecutors, and social services. The country has instituted emergency phones, expanded shelters, and toughened penalties, but the key challenge is anticipatory protection, identifying lethal risk before it becomes fatal. Universal, standardized lethality assessments, automatic firearm removal when a complaint is filed, and integrated case conferences can give institutions a fighting chance to intervene in time.

Brazil: Domestic Violence, Femicide, and the Strain on Services

Brazil’s “Maria da Penha” law is a landmark against domestic violence, providing protective orders and specialized courts. Yet femicide remains a stubborn reality, particularly where police response times lag and shelters are scarce. Economic dependency, sprawling cities, and the normalization of jealousy as a motive all contribute to the cycle. In favelas, women can be trapped between intimate terror and territorial control by armed groups, making exit routes perilous. Promising approaches include mobile protection units that can reach informal settlements, community paralegals who help navigate paperwork, and job-training programs that pair safety with income. Consistent funding and data transparency, publishing real-time metrics on protection order enforcement, build public trust and accountability.

Turkey: Honour Killings, Domestic Abuse, and Policy Whiplash

Turkey’s withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention in 2021 signalled a troubling policy turn, even as domestic laws still outlaw violence and mandate protections. Honour-based violence, murders or assaults carried out under the pretext of family reputation, continues to claim lives, often after a woman asserts autonomy in relationships or dress. Survivors report gaps between formal rights and practical access: restraining orders that are difficult to secure, police who push reconciliation, shelters that are full or far away. Recommitting to international standards matters symbolically and substantively, but immediate steps, mandating police discipline for non-enforcement, funding 24/7 legal hotlines, and prosecuting “mitigating circumstance” claims more rigorously, can save lives now.

United States: Sexual Assault, Coercive Control, and Systemic Attrition

In the United States, sexual assault remains prevalent in homes, workplaces, and campuses. Title IX offers recourse in educational settings, and most states criminalize non-consensual acts and image-based abuse. Yet reporting rates are low, and case attrition, victims dropping out due to fear, disbelief, or procedural hurdles, is high. Coercive control (patterns of isolation, surveillance, and financial abuse) is unevenly recognized in statutes, leaving many survivors with limited remedies unless physical injury is present. Promising efforts include trauma-informed investigation protocols, anonymous reporting portals with pathways to formal complaints, and legal reforms that recognize coercive control as an offence or a factor in protective orders. Robust workplace policies, clear reporting channels, anti-retaliation guarantees, and transparent disciplinary outcomes, are equally essential.

Democratic Republic of the Congo: Conflict-Related Sexual Violence

In the DRC’s conflict-affected east, sexual violence has been wielded as a weapon of war by armed groups and, at times, by state actors. The crimes range from rape during village raids to the abduction and enslavement of women and girls. Survivors face medical complications, social ostracism, and the practical impossibility of pursuing justice where courts are distant and armed actors still roam. Mobile courts and specialized prosecution units have delivered some convictions, showing that accountability is possible even in fragile contexts. But durable change demands security sector reform, protection for witnesses, survivor-centered healthcare, and demobilization programs that include strict vetting to exclude perpetrators from reintegration benefits.

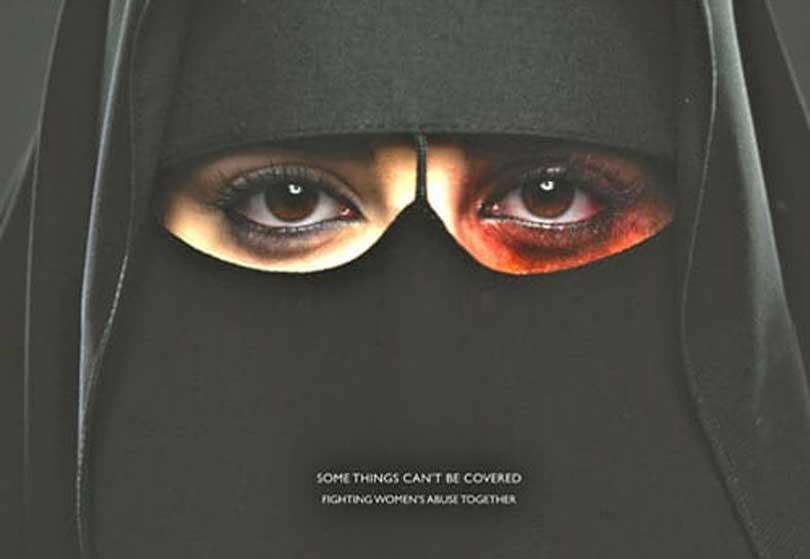

Saudi Arabia: Guardianship-Abuse Dynamics and Domestic Violence

Reforms in Saudi Arabia have expanded women’s public roles, allowing driving, easing travel restrictions, yet guardianship dynamics can still enable coercive control within families, including restriction of movement, forced confinement, and domestic abuse. While laws now criminalize domestic violence and provide hotlines, victims face cultural barriers to reporting and fear of retaliation from male relatives. Practical progress hinges on consistent enforcement, anonymous reporting mechanisms that trigger rapid protection, and shelter networks that respect privacy and long-term independence. Training judges and police to treat guardianship-related coercion as a form of abuse, not a family matter, remains a cornerstone of meaningful protection.

What These Patterns Share, and What Works

Across these ten countries, the crimes differ in form: some are public (femicide, honour killings), others are intimate and hidden (coercive control, digital stalking), and still others are bound up with broader insecurity (conflict-related sexual violence, trafficking). Yet the drivers rhyme: economic dependency, patriarchal norms, weak enforcement, inaccessible services, and justice systems that are slow to act until it’s too late. There is no single fix, but the building blocks of safety are remarkably consistent:

- Centre survivors in design. Trauma-informed policing, survivor advocates in stations and courts, and legal processes that minimize repeated testimony reduce attrition and increase convictions.

- Make protection immediate and practical. Enforce firearm removal upon restraining orders, equip officers with lethality assessment checklists, and guarantee emergency housing and transport.

- Treat digital harm as real harm. Criminalize image-based abuse clearly, require rapid takedowns, and fund cyber units capable of tracing offenders across platforms.

Fund the frontline. The organizations that answer hotlines, staff shelters, and accompany survivors to court are often small and local. Stable funding transforms patchwork into a safety net.

- Publish the numbers. Transparent, disaggregated data on reports, arrests, prosecutions, and convictions lets the public measure progress and hold officials accountable.

- Change the story. School curricula, workplace training, and media campaigns can shift norms from tolerance to zero tolerance, especially among men and boys.

The point of laying out ten different contexts is not to rank suffering or assign blame to culture. It’s to insist that violence against women is not inevitable, and that policy choices, about budgets, training, laws, and leadership, either fuel impunity or dismantle it. When governments and communities choose the latter, women gain not just protection, but freedom: the freedom to walk home, love whom they choose, earn their own money, speak their minds, and imagine futures that violence would otherwise foreclose.