In 2022, Sri Lanka made international headlines, not for triumph, but for tragedy. The island nation plunged into its worst economic collapse in history, triggering widespread shortages, mass protests, and a deep humanitarian crisis. Long queues for fuel snaked around towns, households endured hours of daily power cuts, and the prices of everyday goods soared beyond the reach of many. It was not just an economic breakdown; it was a national trauma.

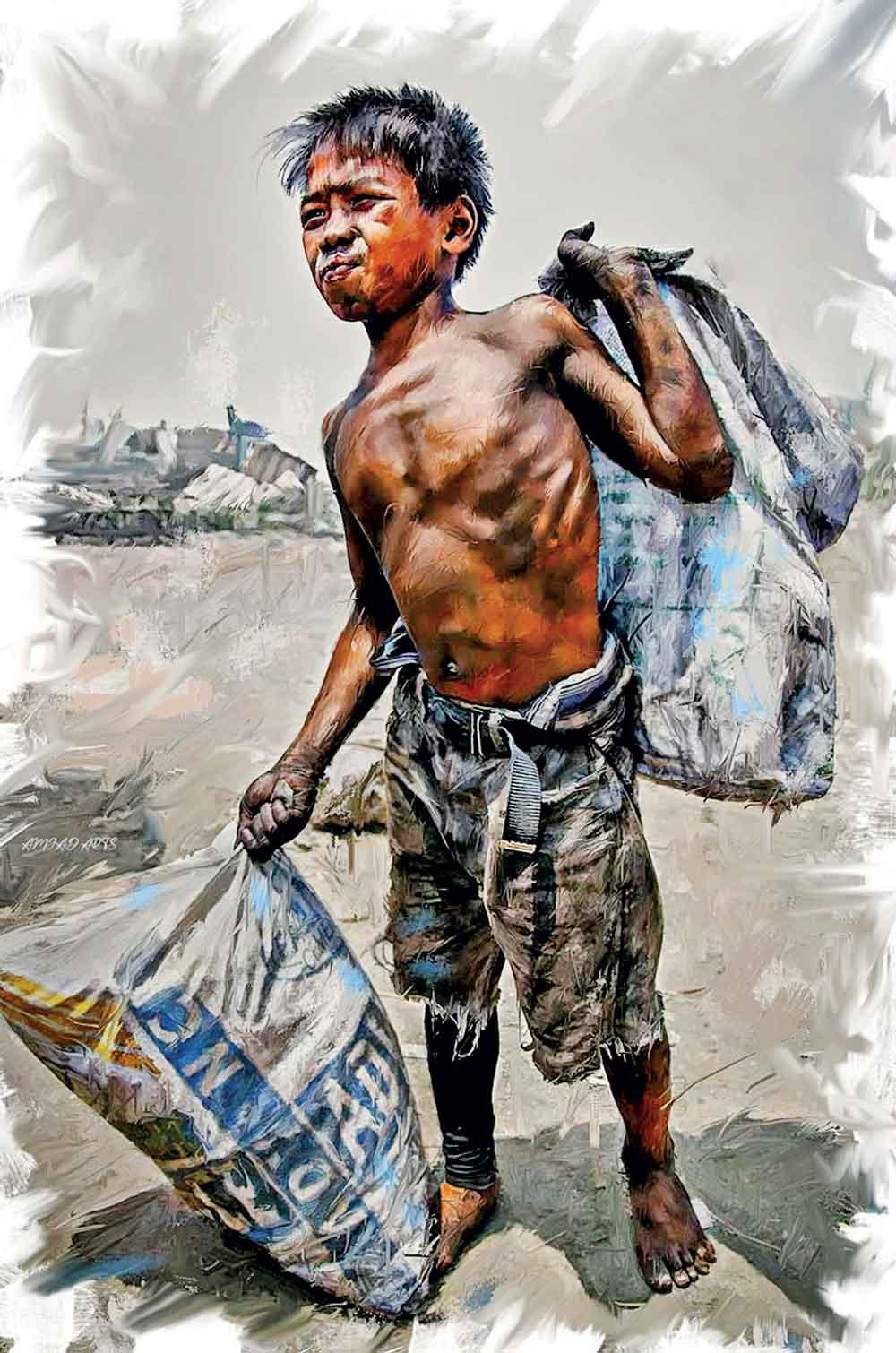

Today, though the government says the economy is stabilizing, that recovery remains far from the lives of many ordinary Sri Lankans. The World Bank reports that around 24.5% of the population is living below the national poverty line in 2024. That means nearly one in four people cannot afford their basic needs; nutritious food, essential medicine, or safe shelter. While cities are slowly showing signs of life, rural and estate areas continue to bear the brunt of the crisis, with jobs scarce and public services limited. Families that once lived modestly but comfortably are now skipping meals, pulling children out of school, or borrowing just to survive another month.

The roots of Sri Lanka’s economic collapse run deep and span several years. A major blow came with the COVID-19 pandemic, which devastated the tourism sector, one of the country’s most vital sources of income. As hotels emptied and bookings vanished, thousands lost jobs, and businesses tied to the tourism chain shut their doors.

The roots of Sri Lanka’s economic collapse run deep and span several years. A major blow came with the COVID-19 pandemic, which devastated the tourism sector, one of the country’s most vital sources of income.

At the same time, government decisions worsened the situation. Major tax cuts introduced in 2019 drastically reduced government revenue. Yet public spending and borrowing continued to rise. As foreign reserves dried up, the country became unable to pay for essential imports like fuel, gas, food, and medicine. When Russia’s invasion of Ukraine pushed global oil and food prices even higher, Sri Lanka was already too fragile to cope. The result was near-total economic paralysis.

The consequences hit daily life hard. Supermarkets saw empty shelves. Pharmacies ran out of key drugs. Public transport became unreliable, and children missed school because there was no fuel for buses. A basic 5-kilo bag of rice that once cost 100 rupees now costs double or even triple, depending on the region. For low-income families, this means choosing between a meal and medicine, or between paying for school and affording the bus fare to work.

While the government insists the worst is over, citing slowing inflation and improving foreign reserves, these figures offer little comfort to those struggling with everyday realities. Economic recovery, on paper, has not yet translated into tangible relief. For many, the crisis isn’t behind them; it’s ongoing.

Job loss has been a particularly painful consequence. Small businesses, family-run shops, farms, and even some factories had to close during the worst of the crisis. Youth unemployment has surged. Even educated young professionals find it difficult to secure stable, well-paying jobs. Those lucky enough to find work often earn too little to survive.

The informal sector, street vendors, daily wage workers, tea pluckers in hill country, has seen incomes fall even as work hours increase. A street vendor in Colombo put it bluntly: “We smile because we must. But inside, we are still worried every day.” Her words capture the quiet resilience of a people forced to adapt to hardship, but they also reflect the emotional and psychological toll the crisis has taken.

In response to the growing poverty, the government introduced or expanded welfare programs. The Aswesuma allowance, aimed at vulnerable families, and the long-standing Samurdhi welfare scheme are now more critical than ever. Financial support has also been extended to elderly citizens, pregnant women, individuals with disabilities, and those suffering from chronic illness. These efforts have offered some measure of relief, but not enough.

Many recipients complain of delays, low payments, or being excluded despite real need. As eligibility criteria tighten and budgets remain constrained, families in genuine distress often slip through the cracks. In rural communities, where access to information and government offices is limited, these problems are even more acute.

Help has also come from international institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, which are providing loans, technical support, and policy advice. The IMF’s 2023 bailout deal was a key step in helping Sri Lanka avoid sovereign default. However, these agreements come with stringent conditions, such as austerity measures and tax reforms, which can be difficult for struggling populations to bear.

Experts emphasize that real, lasting recovery will require more than just emergency loans or economic reforms. It will require deep structural changes, investing in job creation, supporting small businesses, expanding access to education and skills training, and above all, improving governance and accountability. Without addressing corruption, mismanagement, and inefficiency, even the best-designed policies risk failing on the ground.

Sri Lanka’s young people, in particular, need more than just hope. They need real opportunities. Many dream of migrating abroad for better chances, whether to the Gulf, Europe, or Australia. This brain drain threatens to leave the country with fewer skilled professionals at a time when rebuilding requires their talents most.

Still, there are small signs of progress. Tourism has begun to pick up, thanks in part to favorable exchange rates and improved stability. Some businesses are reopening, and entrepreneurial ventures are slowly gaining ground. International confidence is tentatively returning, with foreign investors beginning to explore opportunities. But these improvements are fragile and could easily be reversed if political or economic missteps occur.

For the millions of Sri Lankans waiting for real recovery, resilience has become a way of life. Communities have stepped up to support one another. Faith-based organizations, NGOs, and local charities continue to play a crucial role in distributing aid, organizing community kitchens, and supporting education and health initiatives.

But charity alone cannot replace policy. What Sri Lanka needs is inclusive growth, development that reaches rural families, estate workers, women-headed households, and those outside Colombo’s urban centres. Without it, the divide between numbers and lived reality will only deepen.

In the end, Sri Lanka’s crisis is more than just economic. It is also emotional, social, and psychological. It has tested the very fabric of family, community, and national identity. As one woman in the Southern Province said, “We don’t want riches, we just want to live with dignity again.”

That desire, for dignity, stability, and a chance to build a better future, is what will ultimately drive Sri Lanka’s recovery. But for that to happen, the road ahead must be marked not just by growth, but by fairness, compassion, and meaningful change.