Trincomalee’s Gokanna harbour, still resonant as a pilgrimage centre, is among the few coastal sites where sacred geography retains a living presence

Excavations off its coast have yielded a second-century shipwreck laden with iron ingots, while inscriptions near Ridiyagama document a customs duty allocated directly to local monastic establishments.

Sri Lanka’s dominant historical narratives have long been oriented inland. Its capitals, reliquaries, and irrigation marvels are celebrated as enduring symbols of hydraulic engineering and Theravãda statecraft. Yet beneath this terrestrial imaginary, a more fluid and less commemorated past persists; a past shaped by harbours, crossings, and maritime entanglements. For over a millennium, Sri Lanka was not a land encased by water but a nodal island; an integral participant in the circulatory regimes of the Indian Ocean.

Sri Lanka’s dominant historical narratives have long been oriented inland. Its capitals, reliquaries, and irrigation marvels are celebrated as enduring symbols of hydraulic engineering and Theravãda statecraft. Yet beneath this terrestrial imaginary, a more fluid and less commemorated past persists; a past shaped by harbours, crossings, and maritime entanglements. For over a millennium, Sri Lanka was not a land encased by water but a nodal island; an integral participant in the circulatory regimes of the Indian Ocean.

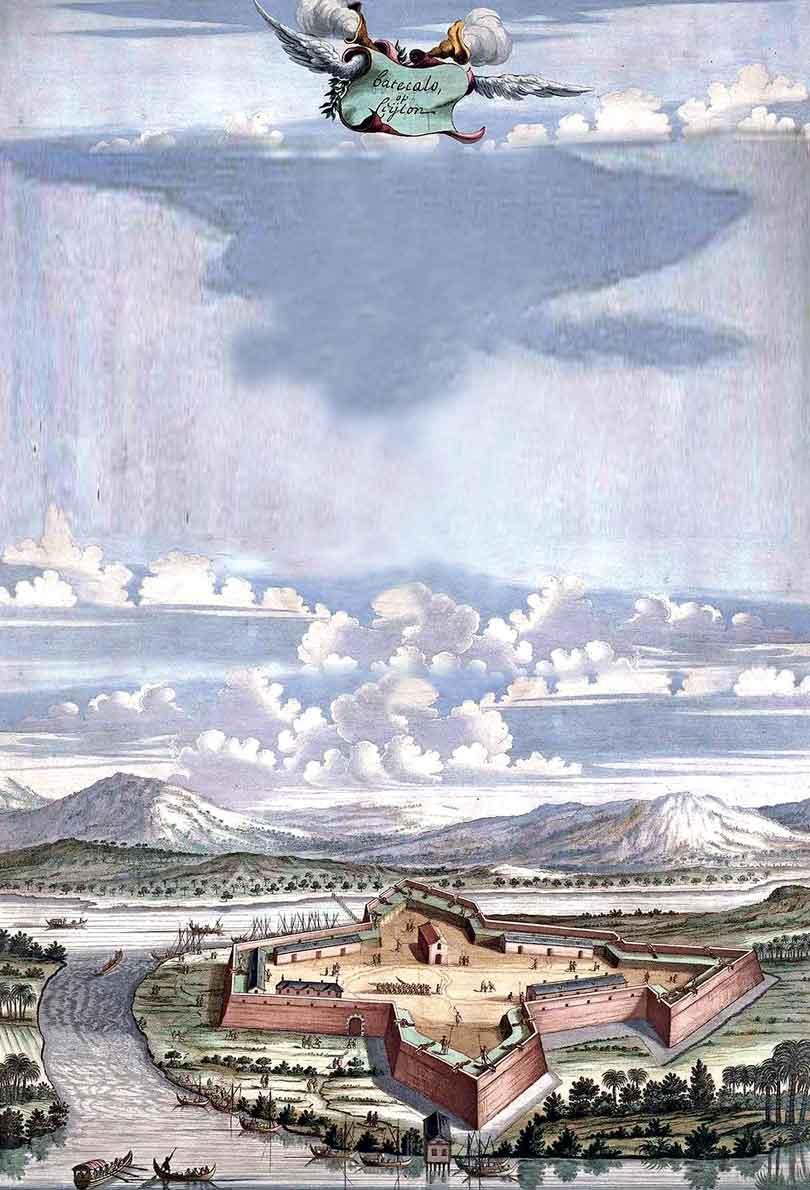

Ports such as Manthai, Godavaya, and Gokanna were not passive gateways; they were sites of political assertion, ritual mediation, and cosmopolitan encounter. Their contemporary marginality within national historiography is not merely a result of environmental decay but, as Michel-Rolph Trouillot reminds us, an outcome of deliberate historiographic silencing, where some pasts are foregrounded while others are actively suppressed in the service of nation-building and cultural consolidation.

Maritime Sovereignty and the Ritual Economy of Ports

Manthai, known in antiquity as Mahatittha, exemplifies this submerged sovereignty. Archaeological layers from the site reveal an archive of Roman aurei, Sasanian glassware, and Tamil Brahmi inscriptions, gesturing toward a longue durée of interregional commerce and diplomatic exchanges (Bohingamuwa, 2017). Classical texts, from the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea to Ptolemy’s Geographia, underscore Taprobane’s position not as an isolated periphery but as a maritime axis where cinnamon, ivory, and elephants became geopolitical currencies.

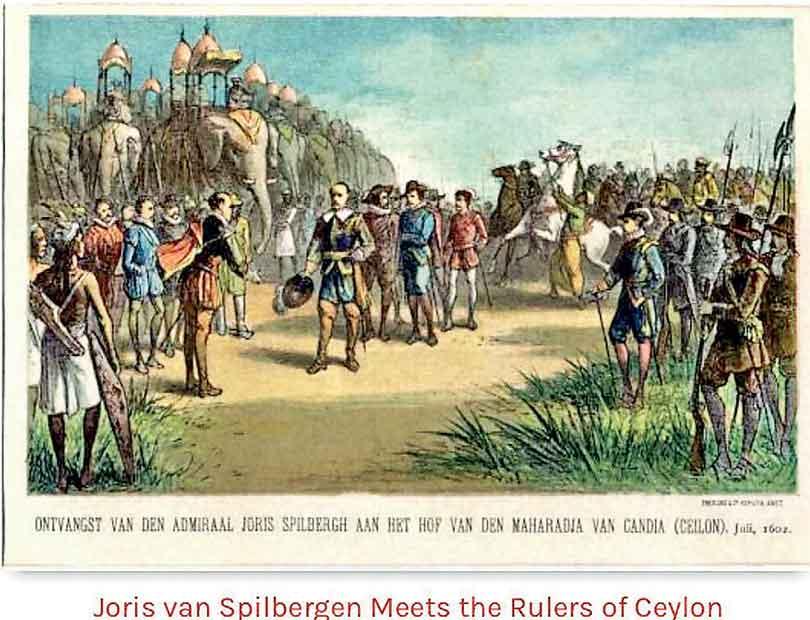

Contemporary Indian Ocean historiography, notably Sugata Bose’s concept of “intercultural circulations”, challenges the land-locked frameworks of statehood by positing the coast as an epistemic and political threshold (Bose, 2006). Within this paradigm, Manthai emerges not as a passive recipient of external influences but as a sovereign port polity, where power was articulated through transactional density rather than monumental fixity. Its significance lay not in its walls but in its role as a site of inter-imperial negotiation and ritualised commerce.

Godavaya and the Coastal Bureaucracy of the South

In the island’s southern seafronts, Godavaya offers a counter-narrative to the inland agrarian orthodoxy. Excavations off its coast have yielded a second-century shipwreck laden with iron ingots, while inscriptions near Ridiyagama document a customs duty allocated directly to local monastic establishments. This record, dating to the reign of Gajabahu I, provides an early glimpse into the fiscal-bureaucratic sophistication of Lanka’s maritime economy (Bopearachchi, 2015). Here, trade was neither informal nor peripheral. It was codified, ritualised, and integrated into the fiscal apparatus of the state-monastic complex. Ports like Godavaya operated as hydro-political frontiers, where economic exchange underpinned both religious patronage and state legitimacy. This challenges the ‘straw man’ perception of Sri Lanka as an agrarian state and mercantile hub by revealing how the Sinhalese state mobilised the sea as both an economic and ideological resource.

Trincomalee, Sacred Thresholds, and the Politics of Passage

Trincomalee’s Gokanna harbour, still resonant as a pilgrimage centre, is among the few coastal sites where sacred geography retains a living presence. The Koneswaram Temple, perched above its azure bay, continues to function as a ritual magnet for Tamil Hindu devotees. Yet the site’s deeper history reveals a maritime palimpsest of religious pluralism, where Buddhist, Hindu, and Islamic forms overlapped, contested, and coexisted. If inland capitals institutionalised kingship through relics and terrestrial processions, ports like Trincomalee ritualised passage itself; enabling not only the circulation of goods but the movement of bodies, beliefs, and cosmologies across fluid frontiers. In this sense, the sea was not absence, but a metaphysical domain which was regulated, navigated, and sacralised within a broader Indian Ocean cosmology.

The Turn Inland and the Production of Amnesia

The inland pivot that followed the Chola and Pandya incursions of the 11th–13th centuries was not merely a military recalibration toward defensible terrain. It represented a cognitive rupture, a recalibration of sovereignty away from the sea and toward ritual enclosure. The Buddhist relic polity, emerging most vividly at Dambadeniya and Yapahuwa, privileged territorial closure and sacred fixity over maritime openness and cosmopolitan exchange. This was not a retreat but a rearticulation of legitimacy, wherein the sea became an anxious periphery; its ports reimagined as porous and disorderly spaces incompatible with the new regime’s bounded orthodoxy. The erasure of the ports from the Sinhala political imaginary was thus an act of ideological governance, not neglect.

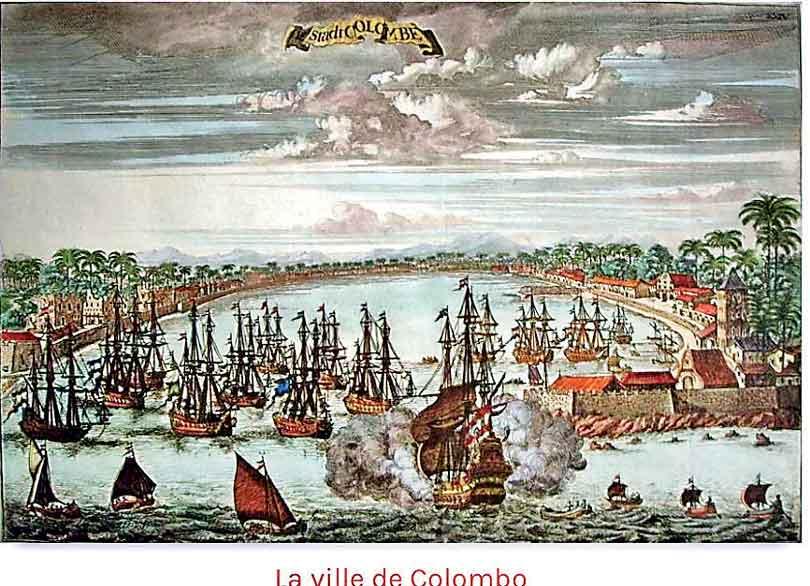

Colonial Cartographies and the Severance of Entanglements

European colonisation did not restore these ghost harbours; it completed their epistemic severance. The Portuguese, Dutch, and British imposed administrative geometries upon previously entangled littorals, transforming ports into extractive nodes rather than intercultural spaces of negotiation. In this colonial-modern cartography, the sea was flattened into trade routes and military supply lines. The fluid cosmopolitanism of ancient ports like Manthai and Godavaya could not survive the logics of empire and developmentalist nationalism, both of which required stable borders and static histories.

Reclaiming the Archipelagic

To reclaim Sri Lanka’s ghost harbours is thus not merely to excavate them as archaeological sites, but to rethink the historical method itself. It requires an epistemological shift from centred, land-anchored narratives toward an archipelagic consciousness, one that acknowledges history as a series of passages, ruptures, and returns. The fragments of Manthai, the submerged bureaucracies of Godavaya, and the layered devotions of Trincomalee demand a historiography that listens from the edge, that thinks historically at sea, that recognises the unfinished work of entangled pasts. These ghost ports are not inert relics; they are living archives of a Sri Lanka that moved, connected, and mattered within wider oceanic worlds; worlds still waiting to be remembered, and perhaps, re-imagined.