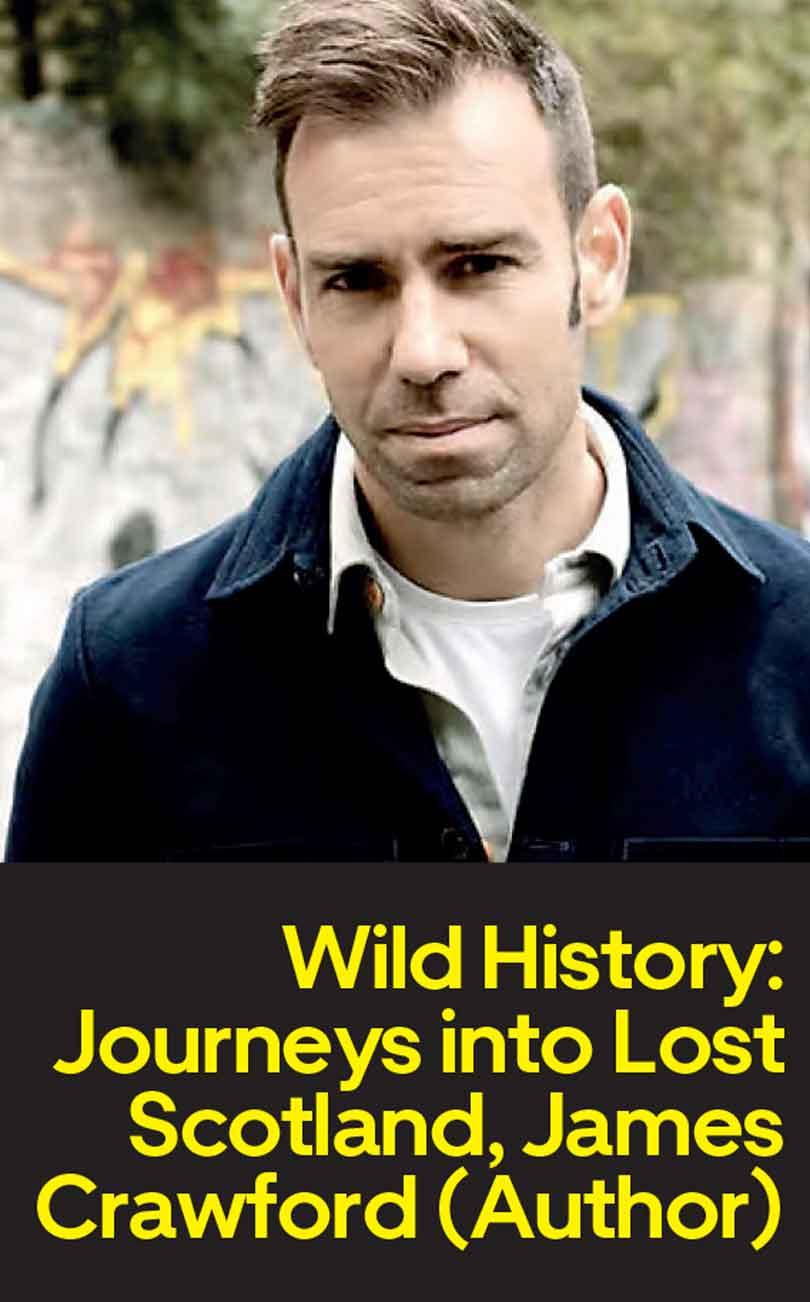

Wild History is a brilliant exploration of hidden historical sites in Scotland. I found the concept of wild history itself very interesting. As the author says, there are very few parts of the world that are truly “wild” anymore; to be wild is to be unadulterated by human activity and by now human activity can be traced to even very remote corners of the globe. But wild history is an exploration of places that people once knew but have now largely forgotten about; places that haven’t been preserved or curated; places that have been abandoned, possibly with the traces of people who once knew about it fading away. James Crawford poignantly illuminates this idea when he says it’s “history set adrift, let loose, let go. History, in some sense, set free.”

Wild History is a brilliant exploration of hidden historical sites in Scotland. I found the concept of wild history itself very interesting. As the author says, there are very few parts of the world that are truly “wild” anymore; to be wild is to be unadulterated by human activity and by now human activity can be traced to even very remote corners of the globe. But wild history is an exploration of places that people once knew but have now largely forgotten about; places that haven’t been preserved or curated; places that have been abandoned, possibly with the traces of people who once knew about it fading away. James Crawford poignantly illuminates this idea when he says it’s “history set adrift, let loose, let go. History, in some sense, set free.”

The book is divided into four sections: worked landscapes, where the environment has been worked for profit, scared landscapes, contested earth, which were sites of conflict, and the section which I especially enjoyed, sheltered landscapes, people’s homes. All the places have a story to tell, and Crawford tells it beautifully.

From ancient burial sites to ruined forts and abandoned towns, the author paints a clear and vivid depiction of each place, before delving into its colourful history. His evocative descriptions are complemented by photographs from his travels. This is a book that sparks wanderlust, in this case for the hidden historical sites of Scotland, but in a wider sense, for the wild histories all over the world. It made me think of all the places that I’d like to see, and what histories I might find there if I ventured off the beaten path. And who knows what sites of wild history you could stumble upon while travelling in Sri Lanka?

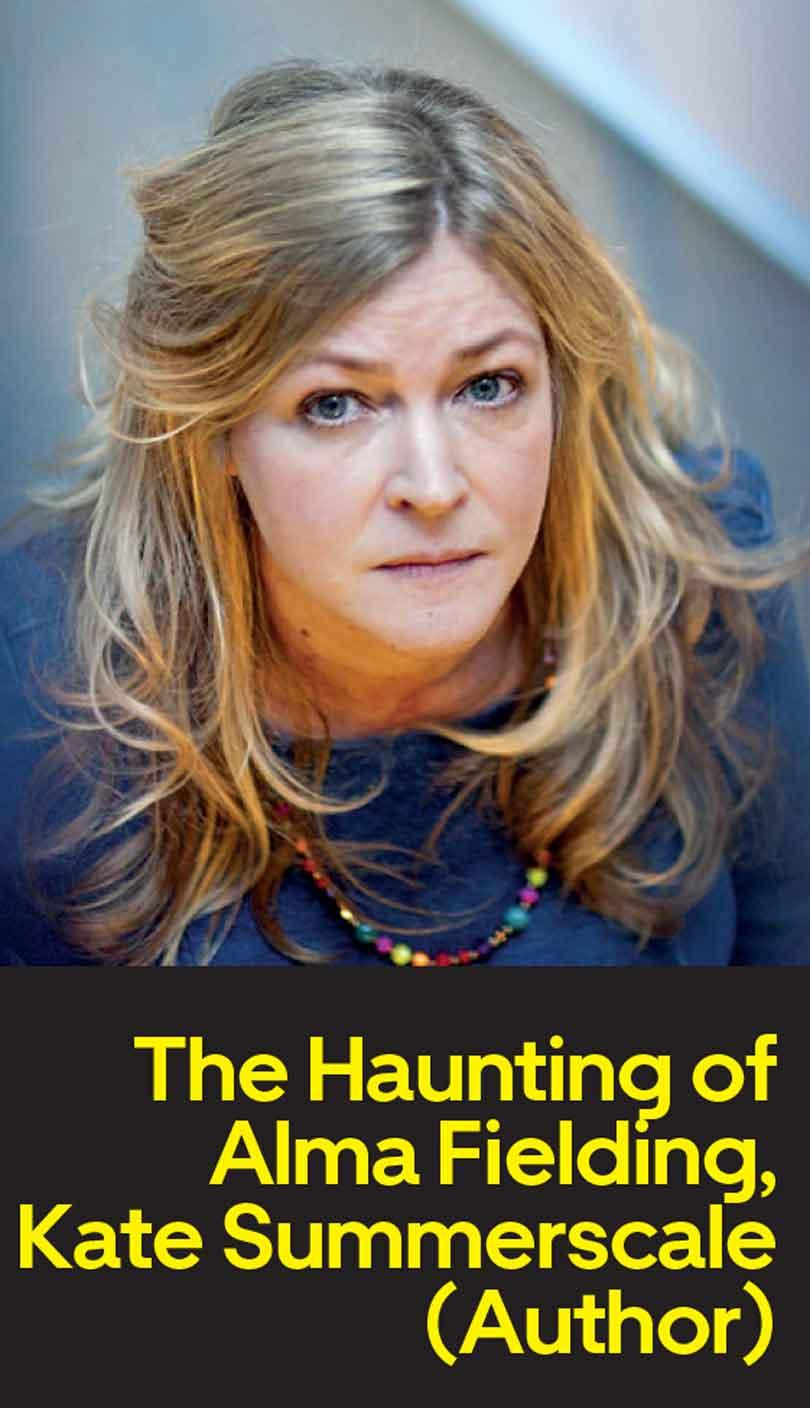

Despite what the title might imply, this is not a horror story, it’s a brilliantly written work of non-fiction exploring the fascinating case of a purported haunting in 1930s London. A young housewife, Alma Fielding, claims to be the victim of a dreadful haunting. In her home in Thornton Heath, china flies off the shelves and eggs smash themselves into cupboards. But the haunting isn’t confined to the house, as instead, it seems that Alma herself is haunted as stolen jewellery appears on her fingers, white mice crawl out of her handbag and, perhaps most strangely in this storm of weirdness, a terrapin materialises on her lap in the middle of a car journey. Her case catches the attention of Nandor Fodor, chief ghost hunter for the International Institute for Psychical Research, an organization that studied psychic phenomena and the paranormal.

Despite what the title might imply, this is not a horror story, it’s a brilliantly written work of non-fiction exploring the fascinating case of a purported haunting in 1930s London. A young housewife, Alma Fielding, claims to be the victim of a dreadful haunting. In her home in Thornton Heath, china flies off the shelves and eggs smash themselves into cupboards. But the haunting isn’t confined to the house, as instead, it seems that Alma herself is haunted as stolen jewellery appears on her fingers, white mice crawl out of her handbag and, perhaps most strangely in this storm of weirdness, a terrapin materialises on her lap in the middle of a car journey. Her case catches the attention of Nandor Fodor, chief ghost hunter for the International Institute for Psychical Research, an organization that studied psychic phenomena and the paranormal.

Fodor initially deduces that Alma is haunted by a poltergeist (German for “noisy spirit”), a ghost known for throwing things around and being a noisy nuisance in general. But, as unbelievable as it sounds, as Fodor’s investigation continues, the case only becomes stranger and stranger. Kate Summerscale’s writing is vivid and engaging. While clearly well-researched, Summerscale’s funny descriptions and compelling narrative read like fiction at times, making the fact that it’s a true story all the more fascinating. Alma Fielding and Fodor lend to the fictional feel of this book: we learn that Fodor has gained infamy for unmasking false mediums, a fact that has made him unpopular amongst psychics and other ghost hunters. Fielding, the eye of the supernatural storm, experienced severe emotional and physical trauma, including several painful medical procedures. They are so interesting that they feel like they could be meticulously constructed literary characters. As the story progresses, readers learn that Nandor explored the idea that instances of poltergeists may not be ghostly activity at all but instead the person at the centre of the haunting could actually be the cause of the haunting; that repressed traumatic experiences could manifest in physical events; for example, objects throwing themselves around. In an interesting mix of psychoanalysis and paranormal study, Fodor proposes this link between suffering and supernatural events. This book is also a glimpse into a turbulent moment in history, just before a second devastating world war. The author provides historical context for attitudes towards the paranormal and explains the trends of the time, such as the popularity of psychics and interest in the supernatural. In a skilled balancing act, the information is extensive and detailed but the writing is accessible and largely entertaining, before taking on a more sombre edge.