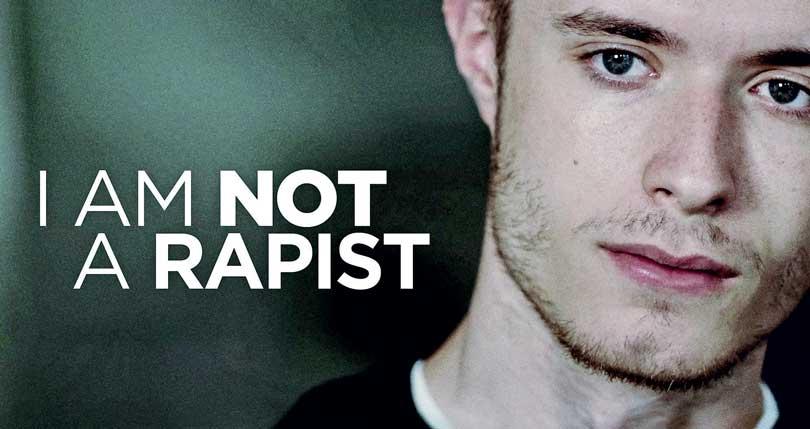

In 2020, British director Huw Crowley released the documentary ‘I Am Not a Rapist.’ The film, now available on streaming platforms, set out to tell the stories of three men who were accused of sexual assault but later cleared of wrongdoing. Through their experiences, the film explores what it means to live under the shadow of a rape allegation, how the justice system can fail both complainants and defendants, and what kind of damage lingers even after exoneration.

At the very beginning, the film sets the stage with statistics that instantly provoke debate. It states that at the lowest estimate, 1,500 men were falsely accused of rape in the UK in the previous year. It also asserts that up to 8 percent of reported rape cases are false. These numbers are designed to grab attention, but they also spark controversy, since the methodology behind them is disputed. The statistics hang over the documentary like a storm cloud, influencing how viewers interpret the stories that follow.

The film is structured around three distinct but thematically connected narratives. Together, these stories provide the emotional core of the documentary, grounding abstract debates in human lives. The first story is that of Jay Cheshire, a 17-year-old student accused of raping a girl he had been dating. The allegation led to a police investigation and an immediate collapse of his world. Though the charges were eventually dropped, the damage was already done. Jay struggled under the weight of suspicion, humiliation, and fear. He never recovered emotionally. After the case ended, Jay tragically took his own life. His story is perhaps the most devastating illustration in the film of how an accusation, even without a conviction, can permanently shatter a young life.

The second case is that of Liam Allan. His story made national headlines when it emerged that the police had failed to disclose evidence that would have cleared him earlier in the process. Liam faced multiple charges of rape and sexual assault. He endured months of uncertainty, public judgment, and the looming threat of a lengthy prison sentence. During his trial, crucial phone messages came to light, messages that contradicted the accusations and would have prevented the case from ever reaching court if disclosed properly. Without that discovery, Liam might well have been wrongfully convicted. His ordeal exposed serious failings in the criminal justice system, particularly around disclosure obligations, and led to calls for reform.

The third man is Ashley, from Abertillery in Wales. He was arrested on suspicion of rape after an acquaintance accused him. Later, she withdrew her statement, but the damage was already profound. Ashley lost his job, fell into debt, and lived under a cloud of suspicion for a long period. Even though no conviction followed, the stigma attached to his name lingered, shaping how others perceived him and how he perceived himself. These three accounts, woven together with interviews and expert commentary, reveal the cascading consequences of a rape allegation. Whether or not the allegations stand up in court, the accused must often navigate life with their reputation in tatters, mental health eroded, and trust in institutions destroyed. One of the central themes of the documentary is the tension between rarity and impact. The film makes clear that false rape allegations are uncommon compared with the number of genuine cases of sexual assault. Yet when they do occur, they carry devastating consequences. The ripple effect extends beyond the accused to their families, partners, workplaces, and wider communities. Careers collapse, friendships fracture, and families are torn apart. The documentary forces viewers to wrestle with this tension: how can something so statistically rare still cause so much lasting damage?

The film also shines a light on the failings of the legal system, particularly in relation to disclosure. Liam Allan’s case illustrates how the failure to disclose exculpatory evidence almost led to a miscarriage of justice. This was not an isolated incident, but part of a broader crisis in the Crown Prosecution Service that has since been acknowledged. The documentary suggests that without rigorous adherence to disclosure rules, innocent people face the terrifying prospect of conviction on incomplete or misleading evidence.

Stigma and public perception play a major role in all three stories. Being cleared of charges does not erase suspicion. Once someone is accused of rape, whispers follow them. Social media compounds the problem, allowing accusations to spread faster and wider than ever before. Even without a conviction, reputations can be permanently scarred. In Ashley’s case, neighbours continued to treat him with suspicion long after the accusation was withdrawn. For Jay, the suspicion and shame were unbearable.

The mental health consequences of false accusations are given significant attention. Jay’s suicide demonstrates the worst possible outcome, but all three men describe lasting emotional trauma. Anxiety, depression, isolation, and self-destructive behaviours are common. The documentary raises urgent questions about what kind of mental health support exists for people in this situation, and whether the current systems are remotely adequate.

The use of statistics is one of the most contested aspects of the documentary. While the film cites figures suggesting that up to 8 percent of rape allegations are false, critics argue that the definition of “false” is often blurred. A complaint withdrawn for lack of evidence is not the same as a proven fabrication, yet both are sometimes lumped together. Official studies tend to place false allegations at a much lower percentage, often between 2 and 4 percent. Critics suggest that the film’s presentation risks fuelling mistrust toward rape complainants, particularly at a time when society is trying to encourage survivors to come forward.

This leads to one of the key controversies around I Am Not a Rapist: balance. Supporters of the documentary argue that it gives a much-needed voice to those who are falsely accused, a group rarely heard in mainstream discourse. For them, the film humanises the accused and highlights serious flaws in the justice system. Critics, however, argue that by centring exclusively on these men, the documentary risks skewing public perception. They fear that it may reinforce scepticism about rape allegations more broadly, potentially discouraging genuine victims from reporting. Another criticism is that the film focuses heavily on emotional storytelling at the expense of systemic analysis. While the human impact is powerful, some viewers feel it leaves unanswered questions about what reforms are needed. Should there be changes in how evidence is disclosed, how suspects are named before conviction, or how mental health support is offered? The film hints at these questions but does not fully explore them. Placing the documentary in a broader context is essential. The presumption of innocence is a cornerstone of the justice system, but in practice, rape allegations test this principle. Unlike many other crimes, rape carries a unique stigma. An accusation alone can alter the course of someone’s life irreversibly. At the same time, sexual assault is one of the most underreported crimes, with many victims fearing disbelief, humiliation, or retribution. Balancing these competing truths is one of the greatest challenges of modern criminal justice.

Media and social media play a critical role. In an era where stories spread globally within hours, accusations can define a person before the courts have a chance to act. Even when cleared, Google searches and social feeds often immortalise the allegation. Once the word “rapist” is associated with someone’s name, erasing it is nearly impossible.

The documentary also prompts reflection on support systems. Those falsely accused often find themselves without adequate legal or psychological support. Families may crumble under the stress, and financial ruin is common. On the other hand, victims of sexual assault frequently find that support services for them are inadequate too. The film indirectly highlights a system struggling to provide justice and care to anyone touched by these cases. The timing of the documentary also matters. Released in the wake of the #MeToo movement, when public consciousness of sexual violence was at its height, it enters a cultural landscape already fraught with tension. Society has been trying to encourage victims to come forward, while also grappling with how to ensure fairness for the accused. I Am Not a Rapist reflects that tension, forcing viewers to ask whether the pendulum of public opinion has swung too far in one direction or whether the film risks pushing it back too far in the other.

As a piece of filmmaking, the documentary has notable strengths. It brings abstract issues down to a human level, showing real lives upended by accusations. It highlights how procedural failures in the justice system, such as non-disclosure of evidence, can have catastrophic consequences. And it makes clear that being cleared does not mean being free from consequences. The long-term damage of accusation lingers long after legal battles end. Yet the limitations are equally evident. At under an hour in length, the film cannot cover the full range of experiences or address the complex systemic reforms that might be needed. By focusing exclusively on the falsely accused, it leaves out the voices of survivors of sexual assault who face their own struggles with disbelief and inadequate justice. This selectivity can create an impression of imbalance. Ultimately, I Am Not a Rapist raises profound ethical questions. How should the justice system balance the rights of accuser and accused? What safeguards are needed to prevent wrongful convictions? How should the media report on allegations without destroying lives prematurely? And how can society both support victims of sexual assault and protect innocent people from false allegations?

The documentary does not provide simple answers. Instead, it provokes thought, discomfort, and debate. It forces viewers to confront the uncomfortable truth that even if false allegations are rare, they can destroy lives as effectively as a conviction. It also reveals that the systems we rely on, legal, media, social, can fail spectacularly, leaving both the innocent and the vulnerable unprotected. For anyone interested in criminal justice, consent law, media ethics, or the sociology of stigma, I Am Not a Rapist offers an important, if harrowing, lens. It is not an easy watch, nor is it meant to be. Its purpose is to unsettle, to complicate, and to force reflection on what justice really means in cases where accusation itself is as destructive as conviction.