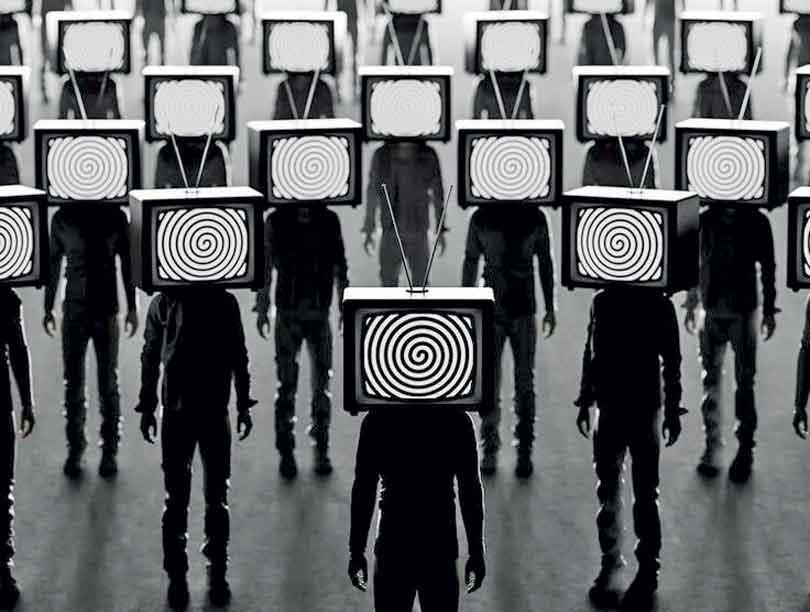

In today’s hyper connected world, war no longer begins with a siren or a missile—it begins with a message. It could be a misinterpreted headline, an edited video, or a manipulated image circulating faster than any official statement. As superpower tensions between Israel and Iran threaten to spill over into a broader global conflict, Sri Lanka, though geographically removed, is not untouched. We feel it in our economy, our diplomatic posture, our shipping lanes, our remittance flows, and in the unspoken worry at every fuel pump queue.

Yet amid this complex web of global turmoil, one entity holds a quiet but profound power: the media. Whether it chooses to inform or inflame, to clarify or confuse, the media is not just covering the conflict—it is shaping it. In fragile democracies like ours, where ethnic tension still lingers beneath the surface and trust in institutions is tender at best, how we are told about the world matters as much as what happens in it.

Media today is not just a mirror to the world; it’s also a magnifying glass and sometimes, tragically, a matchstick.

Journalism as a Lifeline - or a Landmine

At its best, journalism brings clarity to chaos. It guides societies through crisis with calm, verified information, encouraging understanding over hysteria. In Sri Lanka, a multi-ethnic, multi-religious society, this kind of responsible reporting is more than a civic duty—it’s a safeguard against division. But when the media fails—when it sensationalizes, biases, or skips the essential fact-check—it can be as destructive as any weapon.

Misinformation: “Sri Lankan workers in Israel being targeted in airstrikes; dozens feared dead.”

The Truth: “Some areas in Israel with Sri Lankan migrant workers have been affected by recent airstrikes. As of now, no Sri Lankan casualties have been confirmed.”

The difference is only a few words—but those few words can provoke panic, spark communal blame, or result in emotional distress for families with loved ones abroad. This is the power, and the peril, of the media’s pen.

When Journalism Gets It Wrong: History’s Deadliest Headlines

We do not have to look far to find global examples of how media missteps have cost lives. The 2003 Iraq War is perhaps the most infamous case, where the U.S. invasion was justified by claims—echoed uncritically by prominent newspapers—that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction. Those weapons never existed. But the war did. And over 200,000 civilians paid the price.

Then came the 2016 “Pizzagate” conspiracy in the U.S.—a bizarre online lie claiming a Washington pizzeria was a front for a child trafficking ring. It ended with a man entering the restaurant with an assault rifle, convinced he was stopping a crime that never happened.

In 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine, justifying the act with claims of “de-Nazifying” the country—a country led by a Jewish president and Holocaust descendant. Russian media built this narrative with selective history and twisted truths, and the war that followed was real, bloody, and unrelenting.

Closer to our own times, the 2023 Gaza conflict unleashed a wave of AI-generated videos and photoshopped images. Across the globe, including in Sri Lanka, millions shared them, unaware they were watching fakes. Emotional misinformation flooded social media before fact-checkers could even catch up. The digital battlefield became more dangerous than the real one.

Sri Lanka may be a small island, but it sits on the crossroads of maritime trade and ideological tides. When oil prices rise due to conflict in the Middle East, we feel it at the pump. When ports are disrupted, our exporters—tea farmers, garment workers, freight operators—feel it in their pockets. And when misinformation tied to global events enters our domestic conversations, our social fabric is tested.

A poorly worded headline can trigger communal unrest. A misleading video clip can stir ethnic divisions. An unverified report can incite fear, hoarding, and public unrest. We’ve seen this before. We cannot afford to see it again.

Journalism’s Duty in an Age of Distortion

Responsible media must now rise to meet new responsibilities. Verifying facts must take precedence over being first. Explaining context is as important as sharing content. Editors must guard against sensationalism, especially when covering issues that involve identity, religion, or international violence.

Fact-checking should be embedded into the workflow, not slapped on later. Reporters must listen widely, not just to official statements but to the people whose lives are shaped by policy and war. Most importantly, the media must elevate stories of peace, resilience, and human dignity—not just those of destruction and despair.

The Public Is Part of the Problem - and the Solution

But media responsibility does not end in the newsroom. It continues in your hands. Every time you share an unverified article, amplify a misleading photo, or forward a text without context, you become a node in the misinformation network. In times of war and crisis, the way we consume and share news is a form of civic responsibility.

Be curious. Be critical. Ask: “Who wrote this? Why now? Where did this come from?” And if it cannot be answered—don’t share it.

Truth: Misinformation Kills, Too

As Sri Lanka navigates the ripple effects of an increasingly unstable world—from regional wars to disinformation campaigns—our greatest shield may not be military or political. It may be informational. A nation that is informed is a nation that can withstand crisis.

In the end, journalism must do more than report. It must reveal. It must reassure. It must resist the pressure to become another arm of propaganda or panic. Because when bombs fall on foreign cities, and truth is obscured in the fog of war, Sri Lanka will need more than diplomacy. We will need clarity. And clarity begins with what we are told.

Let us not underestimate the war being fought over our minds.

Because when bullets stop, misinformation can still kill.

Note: This article incorporates international case studies, expert analyses, and historical accounts to underline the vital importance of media responsibility-especially in vulnerable nations like Sri Lanka-during times of global

conflict and uncertainty.