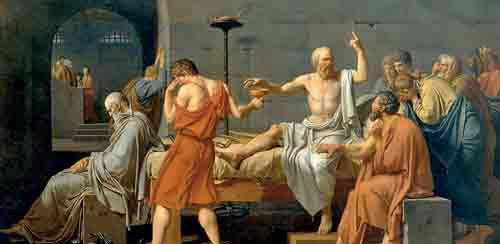

Long before standardized tests and neatly arranged classrooms, education was not about answers. Rather, it was about questions. Socrates, the father of Western philosophy, would stop Athenians in the street in the 5th century BCE and ask, “What is virtue?” “What is justice?”. And he would keep asking, not to trap them, but to awaken them. This was the dialectic method at its peak, inquiry through dialogue and contradiction. It was messy, uncomfortable, and deeply human. It asked students not to recite, but to reflect. Not to memorize, but to wrestle with meaning.

Long before standardized tests and neatly arranged classrooms, education was not about answers. Rather, it was about questions. Socrates, the father of Western philosophy, would stop Athenians in the street in the 5th century BCE and ask, “What is virtue?” “What is justice?”. And he would keep asking, not to trap them, but to awaken them. This was the dialectic method at its peak, inquiry through dialogue and contradiction. It was messy, uncomfortable, and deeply human. It asked students not to recite, but to reflect. Not to memorize, but to wrestle with meaning.

Nalanda and the Fire of Curiosity

In ancient India, at Nalanda, the world’s oldest university, the spirit of inquiry was alive and sacred. Monks and scholars debated with passion and precision. Gautama Buddha, a contemporary of Socrates, encouraged his followers to doubt, to probe, to discover truth for themselves. “Be a lamp unto yourself,” he said. It was a radical idea then. It still is. Nalanda was not a place for rote learning. It was a living, breathing ecosystem of curiosity, where the teacher’s role was not to instruct, but to ignite.

The Griots and the Spiral of Story

Across the African continent, wisdom took a different path through the griots, Africa’s oral historians and storytellers. They preserved not just information, but culture, ethics, and memory. The stories they told did not move in straight lines. They were riddles that moved in spirals, a concept known as zigzag where meaning and truth unfold gradually, through rhythm, metaphor, and pause. This was learning by immersion, not by instruction. Storytelling was not mere entertainment. Rather, it was education. It was how one learned how to live.

From Dialogue to Delivery

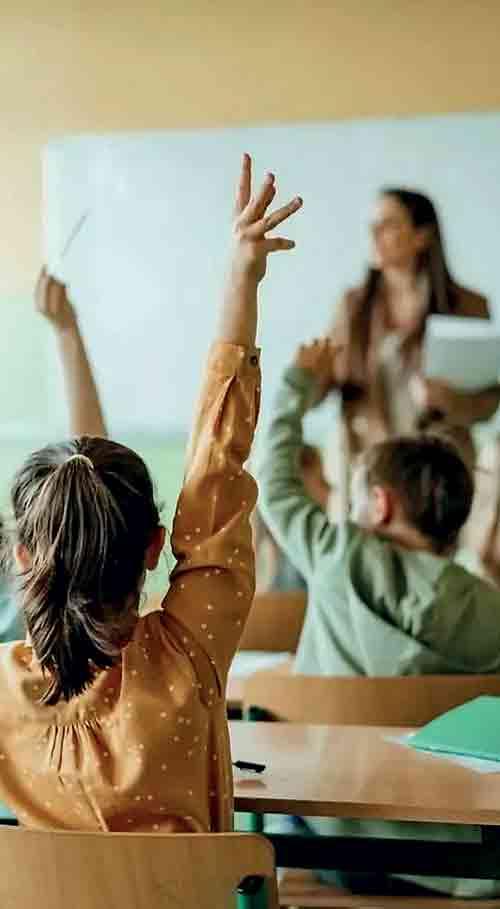

Today, the contrast is stark. In most modern classrooms, students sit silently in rows. The teacher speaks from the front, delivering a pre-determined curriculum. Questions are rare. Conversations are limited. The ancient spark has dimmed.

Thanks to constructivist ideas of scholars such as John Dewey with its focus on group work, peer feedback, and collaborative learning, some effort has been made in recent times to bring the concept of active engagement back into the classroom, but certainly in Sri Lanka, such measures fall short, with the word “constructivist” remaining a mere word. A classroom debate may attempt to mimic the dialectic, but it lacks the spontaneity and spiritual curiosity of Socratic dialogue or Buddhist inquiry. Why, you may ask? Because our system lacks the resources, not just to train teachers to become facilitators of conversations, but worse still because in order to keep up with the demands of the job market, we have either turned our classrooms into factories where the end product is a student who has passed their O-levels, or we have employed teachers who see their profession as a job rather than a calling.

The Crisis of Critical Thinking

Is this why so many students today struggle with critical thinking? Why, they can recall facts but cannot interpret them? Why, they can follow instructions but cannot be bothered to ask why?

We live in an age flooded with information. But true wisdom is scarce. And perhaps this is the root cause: we are still teaching students what to think, but not how to think.

To truly think critically, one must first be allowed to question freely, deeply, and without fear.

That was the gift of ancient cultures and civilisations, be it in Greece, India, or Africa.

The Echoes That Remain

We still hear faint echoes of such ancient traditions, either in the poetry of Kahlil Gibran, whose lines have layer upon deeper layer of meaning, and teach more than any modern lecture ever could, or in the mysticism of Rumi, who challenges his readers to journey inward, to understand truth for themselves. But these are the exceptions, not the rule. Most classrooms today, even in well-funded schools, still treat education as a transaction. The curriculum is king, and the clock is God.

Reclaiming the Lost Art of Education

To truly transform education, we must return not to old facts, but to old ways. We must value to question again.

We must recognize that a good story can carry more truth than a textbook. We must restore the role of the teacher as guide, as questioner, as storyteller. Permit students to ask. Permit them to be confused. Permit them to stray from the syllabus. For it is often in those unplanned moments of quiet reflection that real learning will occur. "Let us ask again, as Socrates did: What is justice? What is truth? What does it mean to live a good life?". And in remembering how we ourselves were once taught by the role models and educators of yesteryear, we might rediscover not only how to teach better, but how to live better.