In the brightly lit aisles of retail stores and the endless scrolls of online shops, fast fashion seduces consumers with irresistible bargains and ever-changing trends. A new dress for $10? Why not? But beneath the thrill of affordable style lies a complex web of hidden costs economic, environmental, and social, that rarely make it to the price tag. This article takes a closer look at the real price of fast fashion and who ultimately pays it.

What Is Fast Fashion?

Fast fashion refers to the rapid production and consumption cycle of inexpensive clothing, designed to mimic the latest runway trends and mass-market styles. Retail giants like Zara, H&M, and Shein churn out new collections weekly or even daily, encouraging consumers to buy more, wear less, and discard quickly. This business model thrives on speed and low prices, creating a culture of disposability in clothing.

Exploitation Behind the Seams

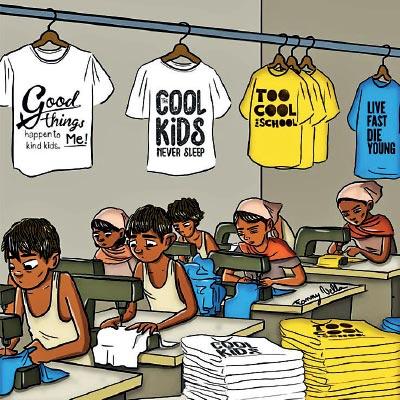

While shoppers enjoy the allure of cheap, trendy garments, the reality for many workers involved in fast fashion production is starkly different. The supply chain stretches across low-wage countries, where factories often operate under harsh conditions.

While shoppers enjoy the allure of cheap, trendy garments, the reality for many workers involved in fast fashion production is starkly different. The supply chain stretches across low-wage countries, where factories often operate under harsh conditions.

- Sweatshop Labor: Workers, many of them women and even children, face long hours, unsafe environments, and wages that barely cover basic living expenses. For example, garment workers in Bangladesh and Cambodia often earn less than $100 a month while producing clothes for global brands.

- Lack of Rights and Protections: Labor laws in manufacturing countries can be weak or poorly enforced. Unionization is often discouraged or outright suppressed, leaving workers with little voice or recourse.

- Mental and Physical Health Impacts: The pressure to meet tight deadlines leads to stressful work conditions and physical strain. Factory fires and building collapses, like the tragic Rana Plaza disaster in 2013 that killed over 1,100 workers, highlight the deadly risks faced by garment workers.

In essence, the “cheap” price tags are often paid with human dignity, safety, and health.

Environmental Damage: The Cost to Our Planet

Fast fashion’s impact on the environment is equally alarming and largely overlooked by the average consumer.

Fast fashion’s impact on the environment is equally alarming and largely overlooked by the average consumer.

- Massive Waste Generation: Globally, an estimated 92 million tons of textile waste are produced annually. Fast fashion encourages overconsumption and quick disposal, turning clothing into one of the fastest-growing waste streams in landfills.

- Water Pollution: Textile manufacturing is water-intensive and pollutes rivers with dyes, chemicals, and untreated wastewater. For instance, the Citarum River in Indonesia is one of the most polluted rivers worldwide, heavily contaminated by textile dyeing factories.

- Carbon Footprint: The production, transportation, and disposal of cheap clothing contribute significantly to greenhouse gas emissions. The fashion industry accounts for roughly 4% of global carbon emissions, more than international flights and maritime shipping combined.

- Microplastics: Synthetic fibers like polyester shed tiny plastic particles during washing, which enter oceans and harm marine life, eventually making their way into the food chain.

The environmental consequences extend far beyond the initial production stage, affecting ecosystems and communities worldwide.

The Illusion of ‘Cheap’

The fast fashion model, while seemingly a boon to consumers, also poses challenges for economies and societies at large.

The fast fashion model, while seemingly a boon to consumers, also poses challenges for economies and societies at large.

- Local Industry Decline: In many developed countries, traditional textile and garment industries have shrunk or vanished under the pressure of cheaper imports. This decline impacts employment and economic stability in these regions.

- Disposable Culture: The “buy, wear once, discard” mentality fosters consumerism and wastefulness, overshadowing values of quality, longevity, and repair. This cycle contributes to resource depletion and societal desensitization to sustainability.

- Questionable Business Ethics: Some brands engage in “greenwashing”, marketing themselves as eco-friendly without making substantive changes. Consumers often struggle to identify genuinely sustainable options amid the noise.

What Can Consumers Do?

Despite the daunting scale of fast fashion’s problems, consumers wield significant influence and can shift the tide through informed choices.

Despite the daunting scale of fast fashion’s problems, consumers wield significant influence and can shift the tide through informed choices.

- Buy Less, Choose Better: Prioritizing quality over quantity can reduce demand for mass-produced, low-cost items. Investing in timeless pieces encourages longer use.

- Support Ethical Brands: Seeking out brands committed to fair labor practices, transparency, and sustainability helps promote responsible production.

- Secondhand and Upcycling: Thrift shopping, clothing swaps, and creative repurposing extend garment life and reduce waste.

- Care and Repair: Proper garment care and mending can delay disposal and keep clothes in circulation longer.

While individual actions alone cannot fix systemic issues, consumer demand can pressure brands and policymakers to adopt more ethical and sustainable practices.

Industry and Policy Responses

Recognizing fast fashion’s drawbacks, some industry players and governments are beginning to act.

- Sustainability Initiatives: Major brands are exploring recycled materials, eco-friendly dyes, and circular business models aimed at reducing waste.

- Legislative Efforts: Countries like France have introduced laws banning the destruction of unsold clothing, encouraging donation or recycling. The European Union is pushing for stricter regulations on textile waste and transparency.

- Transparency and Accountability: Technology, such as blockchain, is being used to trace supply chains, enabling consumers and watchdogs to verify ethical claims.

However, critics argue that these steps are often incremental and insufficient given the scale of the problem.

The Future of Fashion: A Balancing Act

The dilemma fast fashion presents is a microcosm of broader global challenges: balancing economic growth with social justice and environmental stewardship. As awareness grows, there is hope for a more thoughtful, circular fashion economy, one that respects the people who make clothes and the planet that sustains us all.

Still, for that to happen, it requires more than just consumer goodwill. It demands commitment from brands to prioritize ethics over profits, governments to enforce stronger regulations, and society to redefine what value means in the context of fashion.

Conclusion

Fast fashion’s low price comes at a steep cost borne by exploited workers, damaged ecosystems, and a culture that normalizes waste. The next time a bargain tempts you, remember: “Cheap” isn’t truly free. The hidden costs ripple far beyond your closet, affecting lives and the planet in ways that demand our attention and action. Only through collective awareness and responsible choices can the true price of fashion be fairly shared, and ultimately, reduced.