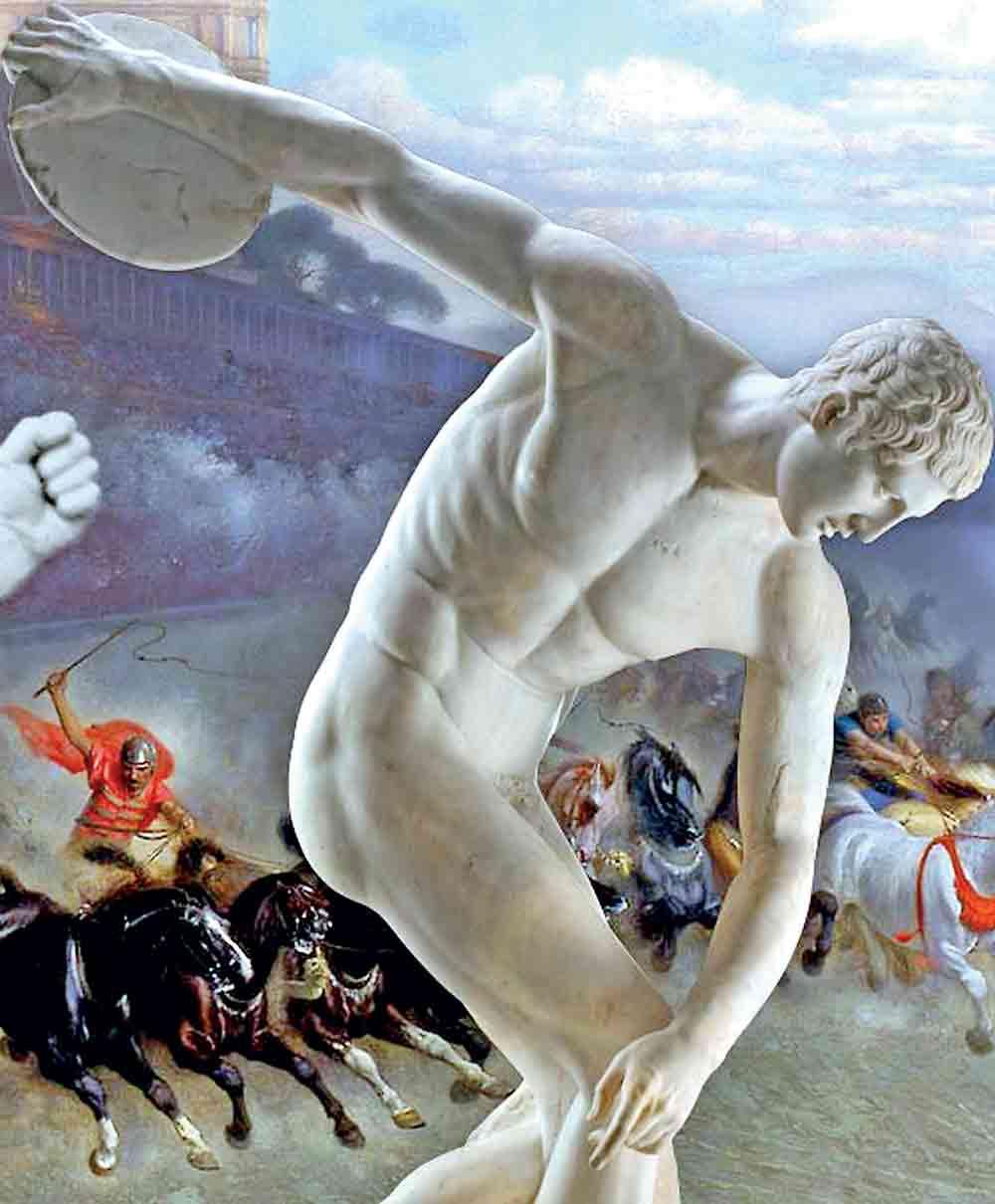

Long before sports became a medley of branded jerseys, papare bands, and parents arguing with referees, they served a far more brutal purpose: preparing men for war. The Spartans, ever practical, perfected this. Their boys (as young as seven years old!) were not “training”; they were being hardened, sculpted, and occasionally terrorised into becoming soldiers. Sports were not about enjoyment or self-expression. Rather, it was about survival. The earliest Olympians were simply demonstrating the physical supremacy their city-states relied on. Victory was not a matter of pride alone; it was a declaration of military capability.

Long before sports became a medley of branded jerseys, papare bands, and parents arguing with referees, they served a far more brutal purpose: preparing men for war. The Spartans, ever practical, perfected this. Their boys (as young as seven years old!) were not “training”; they were being hardened, sculpted, and occasionally terrorised into becoming soldiers. Sports were not about enjoyment or self-expression. Rather, it was about survival. The earliest Olympians were simply demonstrating the physical supremacy their city-states relied on. Victory was not a matter of pride alone; it was a declaration of military capability.

Over time, however, the spear was replaced with the javelin, the battlefield with the stadion, and the survival imperative morphed into the idea of sport as spectacle. Skill became something to showcase rather than merely deploy. And thus began humanity’s long love affair with competitive athletics - not as preparation for conflict but as a socially sanctioned stage for the demonstration of skills.

Fast-forward a few thousand years, and we now inhabit a world where sports can be defined as much by those who watch as those who play. Enter spectator sports - events whose primary energy comes not from the athletes but from the audience. In theory, this is entirely harmless. After all, what is wrong with watching cars go round and round the same racetrack at 300 km/h, while pretending we understand strategy, tyre compounds, or “dirty air”? Formula One fans find it thrilling; the rest of us politely pretend to appreciate the aerodynamics!

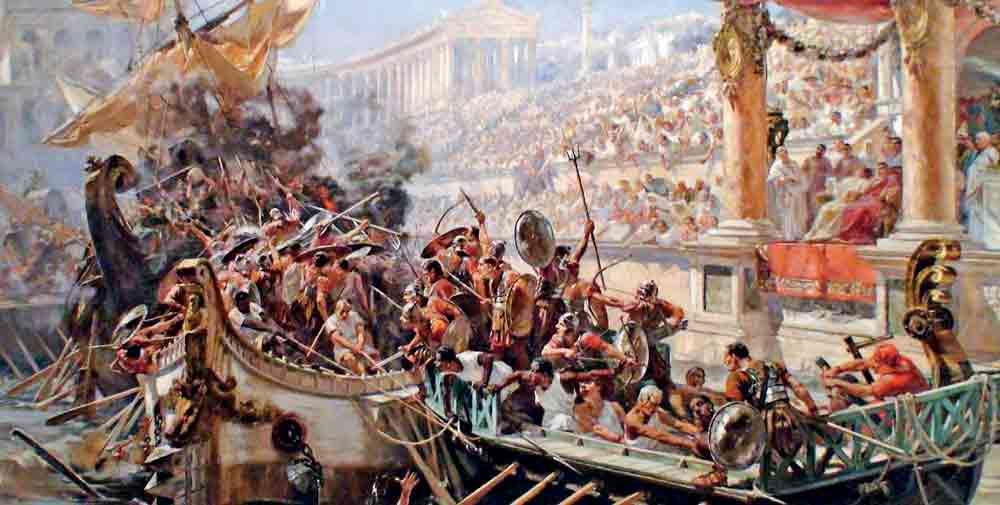

But some sports go a step further. Kickboxing. Wrestling. Mixed martial arts. These invite us not only to watch but to enjoy the controlled violence. And here, an uncomfortable question arises: what does this say about us, the supposedly civilised, 21st-century spectators? That we take pleasure in someone else being punched to the point of disorientation? How different are we really from the Romans who once cheered as “Christians” were mauled to death by lions in the Colosseum? Today no lions are involved (thankfully!), and the violence is consensual, welllit, and regulated by federations with acronyms. But the thrill we seek - the adrenaline of watching bodies collide - is disturbingly familiar. Is our appetite for controlled violence really so different from ancient bloodlust, or have we simply learned to package barbarism in sportswear and broadcast it in high definition? Perhaps civilisation changes only in form, not in instinct.

Yet to dismiss spectator sports entirely would be unfair. They unite communities. They offer catharsis. They provide harmless escapism in a world that grows heavier by the day. A good match, whether it is football, tennis, or cricket, can mend friendships, ignite collective joy, and even inspire the young to pick up a racket or run a lap. But the ugly side of spectator sports cannot be ignored either. Aggressive fandoms, pitch invasions, online harassment, and the bizarre belief that paying for a ticket entitles one to dehumanise the players by hurling insults at them, are all worrying trends of spectators becoming participants in the worst possible ways.

And this brings us back to students.

When young people watch sports, they see the glamour, the applause, the viral celebrations. What they rarely see (unless adults bother to point it out!) is the discipline behind the discipline: the training at dawn, the routine, the commitment to physical and mental balance. Spectator sports show the final act, not the rehearsal. Children need the full picture, especially in a world where they swing between apathy and burnout.

Schools and parents must therefore steer the conversation: enjoy the spectacle, yes, but learn from the sport. Admire the victory, yes, but respect the grind. Watch the heroes, yes, but understand that the values worth emulating come from the locker room, not the spotlight. This also highlights the importance of participation, for a child who plays sport learns teamwork, perseverance, grit, and the art of accepting defeat without losing one’s determination. Whereas a child who only watches sport absorbs only the drama. And drama, as we know, is rarely a stable foundation for character.

Given all this, the bigger question emerges: can sports change society? Can the virtues practiced on fields and courts ripple outward and shape the way we treat one another? Possibly. But if history teaches us anything, it is that society has a habit of circling back to its old ways, rather like those Formula One cars racing round the same track. Today we celebrate discipline; tomorrow we might celebrate spectacle. Today we emphasise teamwork; tomorrow the world may reward selfishness again.

So perhaps the more relevant question is not whether sports can change society, but whether they can anchor students in a world that constantly shifts. The values they learn, be it resilience, balance, perspective, or humility, are not trends. They are habits of mind and habits of living. And unlike society’s fleeting moods, they are durable.

Sports cannot prevent the cycles of history from repeating. But they can equip the next generation to navigate them with steadier hands. And in a time when instability feels like the only constant, that may be more valuable than any trophy.