People always ask us, “Where to next?” Like we’re always supposed to have an answer. The truth is, we’ve been circling Colombo for the longest time, sticking close to what we know. It’s not that the city’s magic has run dry, but something in us started itching for the unfamiliar, a craving for something different. This time, I got to choose. And I said, “Negombo.”

Why? No real reason. Maybe that was the beauty of it. It felt random enough to be right.

Our usual transport savior, Kithsiri. Anyone who’s traveled with Kithsiri knows he’s more than a driver. He’s a companion, a storyteller, and with nearly 15 years on the road, a calming force in our chaotic getaways. The crew was small: Pathum, Yahsmitha, Chamara, and me. Tharindu was off playing the long game, on a date, finally. Gayantha stayed back, gently nudged into taking one for the team. We’re juggling too many operations anyway, especially outside of writing, “With a boomer.” As we like to say.

“Can you check the Google weather and see if it's raining?” Pathum asked. I lied and said it wasn’t. The sky, of course, betrayed me. The moment they got into the van and saw the grey overhead; I became public enemy number one. But I had an ally, Yahsmitha, seated next to me a rare occurrence, which meant this time I could fight back against the boys.

I was supposedly navigating through sub-roads, but by the time we were halfway, the first marker arrived. Not a landmark, but a scent.

It hit us the moment we neared the coast. That deep, briny smell of raw fish; sharp, unmistakable, overwhelming, and honest. Negombo didn’t hide what it was. This was its soul, its beating heart. The scent carried stories, stories of men who dove into these waters every day for survival. Yet somehow, it looked like home to them. They don’t care how it should look to outsiders. They have their own way of living, a system. And they've formed a community that thrives within it. A great one, at that. They seem content, even happy.

We passed boats, some grand, some barely afloat. Each had names that made us laugh. One read Leesa Duwa, and it had us in fits. It was culture. It was identity. It was resilience on full display. And I thought to myself, how dare anyone call this “just Negombo?” It’s a communication method. A way of feeding people honestly and with effort.

Then it rained. Of course, it rained. Pathum and Chamara turned to me with that look. You know the one. I muttered something about being “blessed,” but even I couldn’t spin it convincingly. Pathum ran with his grandmother’s floral handkerchief over his head—completely useless but somehow comforting. Meanwhile, Chamara and I were protected under the giant umbrella. Naturally, I saved him first. He insists on being the main character. He might as well get the treatment.

Thirty years in the game. Priyantha rides a bicycle every day to the Lellama market, a wooden box strapped to the back. He travels from Negombo to Minuwangoda with about ten kilograms of fish. Some days, he comes home with half still unsold. But he keeps going because this is his business, one that gives him freedom despite its instability, one that makes him feel alive.

Beside him, another man, holding a rod. He recoiled. “I’m not a fisherman,” he said. “This is just a hobby.” His name was Priyantha Lal. It struck me how ashamed he was to be mistaken for someone who fishes for a living, as if it might make us look down on him. How even in a place as raw and real as this, people still worried about perception.

We were on our way to the direct fish market when the conversation shifted, inevitably, to breakfast. In a town like Negombo, where the air is thick with salt and the sea’s leftovers, breakfast comes wrapped in wax paper. I held a bun stuffed with dry fish sambol and took slow sips of a Highland chocolate milk. In the lagoon, cranes were wading through the water, trying to snatch up fish. One almost choked trying to swallow a catch that was too large. Chamara, knowing me all too well, made sure I saw the entire struggle, even almost trying to swim in to save the fish.

At the market, Yahsmitha brought a face shield to help filter the odor. Knowing Chamara and how he is, I didn’t even bother to do the same. Looking at Yashmitha, Chamara quipped, “If you’re not going to experience it fully, stay in the van.” In response, Yahsmitha threw the shield. None of us ever saw it again.

The market felt like a shouting match layered over the cries of crows and the slap of fish hitting scales. A symbiotic chain of chaos, where everyone benefits. The smell is relentless, the energy magnetic. We spoke to Rangana, who has been in the fish business for over thirty years. He brings over 15,000 kilograms here, making it a profitable endeavor. “We know exactly which customers need what, and where,” he explained. Distributors come to him, and relationships built on years of mutual trust are what sustain this place. But even in this network of loyalty, Rangana admitted the hardest part is lending money. “They promise to pay later… many don’t. But how do you stop? Their families need to eat too.”

He got emotional. And for good reason. This is survival. Nature and human effort blending into something deeply Sri Lankan. Fishermen continued netting sprats nearby, pulling them from the water in practiced motions. It felt like a quiet performance of identity. It struck me how life and death often exist side by side here, like tides brushing the same shore.

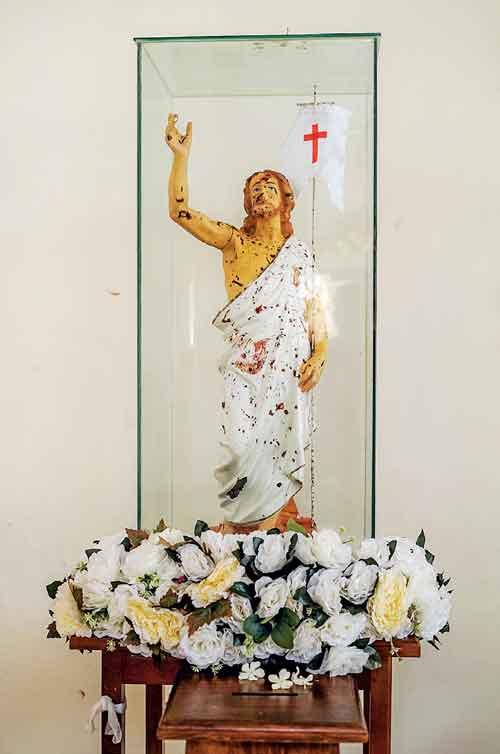

Next to St. Sebastian’s Church in Katuwapitiya, a place that carries immense emotional weight. As we entered the church, guarded by two army personnel, they didn’t welcome the fact that the media had arrived unannounced. So, we clarified. We were just visitors. They let us pass.

Inside, the silence was piercing. Crows cawed, birds fluttered, and the weight of grief hung thick in the air. It was haunting to relive what I had once only seen in news footage, the blood, the devastation, the injustice. How could something so ugly, so senseless, happen here?

The air was moist. Every step felt like walking through memories not yet laid to rest. But it also felt alive, as though those lost were still there, inhabiting the very bones of the church.

Locals still return here, seeking comfort. A comfort that the system, one that was supposed to protect them, failed to provide. It failed them. It failed their neighborhood. It failed us. It failed humanity.

But among the memories preserved is one that haunts: the glass box containing the exact site of the bombing. The wall behind it still bears the massive scars, holes at least two centimeters deep. Pathum asked me, “Why do they still glass the area of the explosion? Why preserve it like this?”

I answered, “That’s the awareness. That’s how we remember. That’s what keeps us awake. We can’t correct what we don’t acknowledge. We must keep it alive until justice is served.”

That justice, however, feels far away. The current government, which once promised answers in every campaign rally, has fallen silent. As Dominican Sister Sirima Opanayake, principal of the Ave Maria Branch School near the church, put it: “We’re sure they’re already saints in heaven. But we are still waiting for justice.” She lost seven students in the attack.

Chamara broke the silence as we left. “Don’t make this piece about that,” he said. “Let people feel like this is home again, not just a place of tragedy.”

I nodded, but I had to add something.

Yes, St. Sebastian’s is a beautiful church, one that continues to answer the prayers of its people. But its cracks, its glass boxes, and its silence speak volumes. It holds memory like a sacred relic.

And we must listen.

Then we headed out for lunch at Coronation Restaurant, Serving Since 1953, in Negombo. There, we met the third-generation operator, Malinka Weliwita, who now runs the establishment started by his grandfather. While at the venue, we also noticed an 83-year-old man named Sam collecting coins just to enjoy a beer at the restaurant. Malinka smiled and said, “That’s our community. That’s who we cater to. The rustic heart, not the luxury. It’s about someone feeling at home, having good food, and being in a comforting place. A place that screams Negombo and Sri Lanka.”

Malinka was adamant we take the boat ride to Winsan Island in the heart of Negombo Lagoon. As we glided through the Dutch Canal, the lush green mangroves and the hum of wildlife left us breathless. Also, fresh breath. Monkey Island was pure amusement.

Dozens of baby monkeys chased each other through the branches, playful and free. Crab traps dotted the water, silent reminders of the livelihood that binds this community to the sea. And beyond it all, the skyline was dotted with the elegant silhouettes of churches; a reminder why Negombo is lovingly called “Punchi Rome,” Little Rome.

A statue of Jesus stands serenely in the middle of the Negombo Lagoon. This statue is a landmark often visited during boat tours. Locals believe the statue possesses miraculous powers, and it has become a place of quiet reverence. The lagoon’s shallowness made it possible to walk toward it. Pathum, always the one to embrace the full experience, waded into the water. I, however, couldn’t risk it.

That moment was a breath of something rare: raw tourism, untamed nature, and soulful spirituality. It made us pause and ask ourselves why we rush to escape this island when it still holds so much we haven’t seen.

We were exhausted. Chamara leaned back and said, “This was the best ‘boomer’ we’ve done.” I laughed and said, “I love that for you.” Back in the van, Kithsiri cracked a joke about us being too soft for field life.

A city with its own identity, its own people, and a rhythm so different. Different. That’s what this whole day had been. Not better. Not worse. Just different.

And different, we realized, was exactly what we’d needed.

Negombo’s beauty, I realized, isn’t wrapped in politeness or polish. It’s loud, it’s rough, and sometimes, it’s cautious. But it’s real. Awareness that sometimes translates into unresponsiveness or even rudeness. And yet, it’s all part of the layered experience that makes this place so human.