Took Up Arms and Unmade Dynasties

- Kassapa V inherited a fractured kingdom and a royal court increasingly dominated by monastic voices. He was himself a learned man, celebrated in the chronicles as a patron of Pāli literature and a compiler of grammatical treatises.

01.The Monk with the Sword

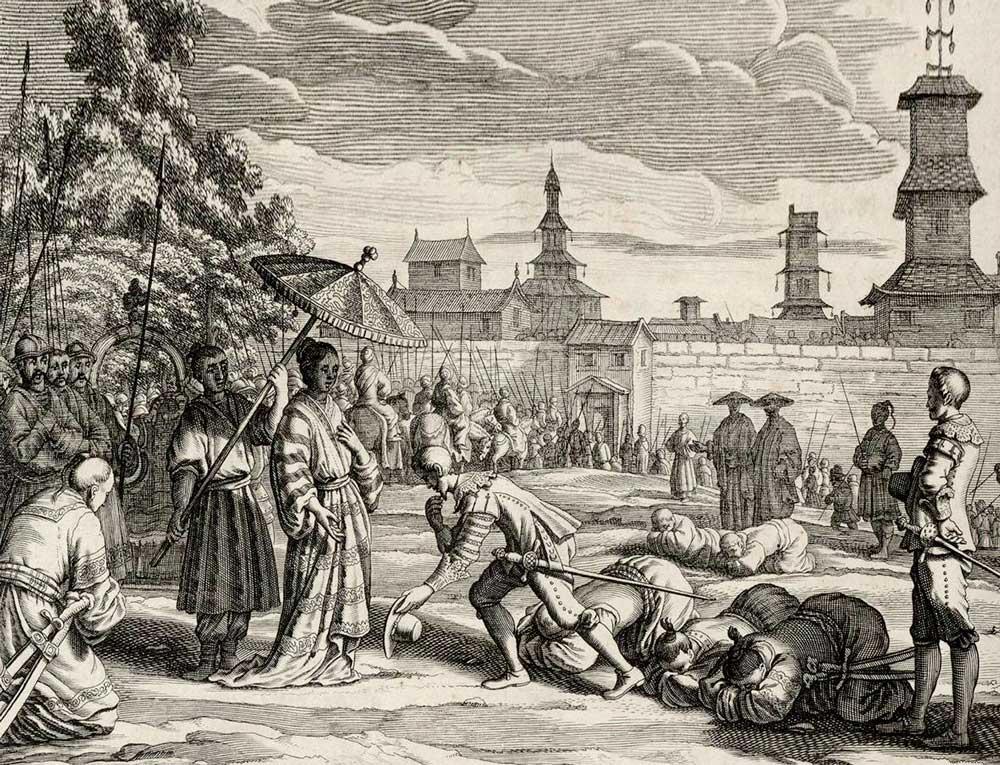

We are often told that Sri Lanka’s past is shaped by serene kingship and pious monks, by white-robed devotees and relics borne under golden canopies. Yet history, like the chronicles that narrate it, is seldom so still. There are moments, hidden in footnotes and inscriptions, where those who donned the saffron robe also gripped the sword, where monasteries were not only sites of worship but of war. And there were times, rare and turbulent, when monks did not merely bless kings; but unmade them. The Cūḷavaṃsa, the great continuation of the Mahāvamsa, offers us tantalising hints of this disruption. In a time of dynastic fracture and foreign conquest, it was not always the king who acted as protector of the faith. Sometimes it was the sangha itself that turned to violence, to preserve its place in the world. This is the story of such monks, those who, cloaked in piety, walked into the theatre of war and emerged as kingmakers. And, in at least one case, as a king killer.

02.Kingship and the Sangha:

An Uneasy Alliance

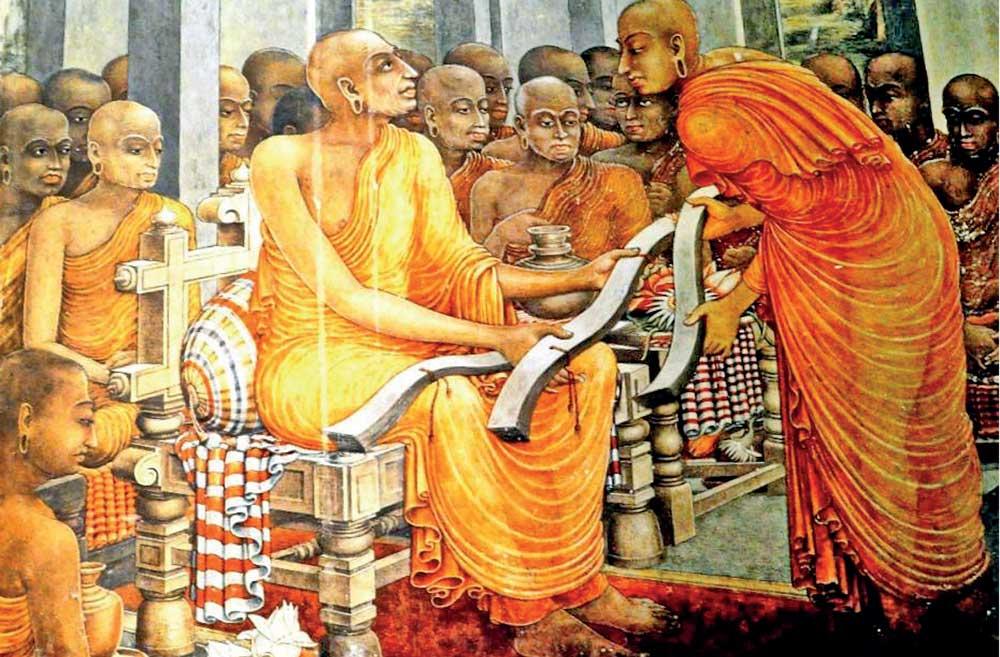

In theory, the relationship between the monarch and the sangha was one of reciprocal reinforcement. The king, as dhammarājā, safeguarded the sāsana; the monks, in turn, sanctified his rule. Yet from the 8th century onward, this compact began to strain. The fragmentation of the Anuradhapura kingdom, the pressure of Tamil mercenary rule, and the rise of regional power bases, particularly in Rohana, unsettled the axial balance between crown and cloister. The sangha was not a singular body. It was a landscape of factions: the Mahāvihāra, the Abhayagiri, and the Jetavana were all centres of differing philosophical schools and political loyalties. Monastic figures began to appear in places unexpected: not merely as abbots or ritualists, but as administrators, informants, even tacticians. They were landholders, tax beneficiaries, and legal arbiters. The Cūḷavaṃsa quietly records that some monks “counselled” kings during crises; others “provided protection” for princes in exile. But in the reign of Kassapa V (r. 914–923 CE), we see something more startling.

03.Kassapa V

and the Cloistered State

Kassapa V inherited a fractured kingdom and a royal court increasingly dominated by monastic voices. He was himself a learned man, celebrated in the chronicles as a patron of Pāli literature and a compiler of grammatical treatises. But his court was, by all accounts, suffused with religious authority, not merely ornamental, but functional. One of the most revealing sources is an inscription at Dambulla, where a monastic order is granted both land and legal exemption, a marked sign that the monks were not merely being appeased but entrenched as parallel administrators. According to Gunawardana (1965), Kassapa elevated certain monks to permanent status of royal advisors, a departure from previous conventions of clerical detachment. Yet it was this very proximity that may have proven volatile. In later segments of the Cūḷavaṃsa, we read of a court faction [allegedly led by a “renunciate of the South”] who orchestrates a campaign to remove a rival princeling under Kassapa’s protection. The passage is obscure, cloaked in ritual euphemism, but the implication is clear: the sangha was no longer above politics. It had become an instrument of it.

04.Vijayabahu I and the Armed Ascetic

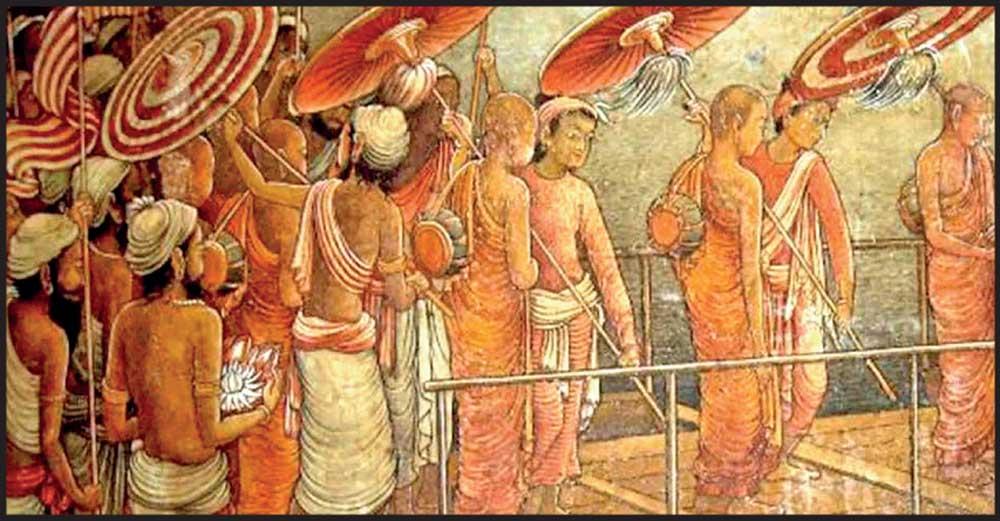

The most dramatic case, however, is that of Vijayabahu I (r. 1055–1110). Crowned as saviour of Sinhala sovereignty after nearly a century of Chola occupation, his rise is narrated in triumphant tones. Yet the Cūḷavaṃsa reveals more than patriotic warfare; it reveals the strategic use of monastic power to mobilise militarism. While in exile in Rohana, Vijayabahu was sheltered by a network of monks and provincial strongmen. According to Peebles (2006) and Strickland (2011), these monks did more than offer refuge. They raised militias, coordinated supply lines, and invoked Buddhist prophecy to rally support. In effect, they waged a holy war, framing the Chola presence not merely as foreign occupation but as a dharmic violation that required ritual cleansing, the chronicles record that Vijayabahu, upon ascending to the throne, restored temples, reordained monks, and held massive almsgivings to cleanse the realm. But this theatre of piety was the second act. The first was staged in blood and forest, and it bore the signature of monks turned tacticians.

05.The Paradox of Sacred Violence

How do we reconcile the image of the peaceful monk with these accounts of clerical insurrection?

To begin with, we must discard the simplistic binary of sacred vs. profane. In medieval Sri Lanka, violence could be purifying, kingship could be monastic, and the sangha could act in defence of not just the dhamma but of property, status, and survival. Religious orders had much to lose when foreign rulers-imposed strange rituals, seized temple lands, or patronised rival sects. As De Silva (2012) observes, the sangha often acted as a guardian class, ideologically pacifist, but materially pragmatic. When kings failed to protect the sāsana, monks stepped in. Sometimes with scripture. Sometimes with strategy.

06.King Killer?

And yet, even within this grey space, one episode haunts the record.

A late segment in the Cūḷavaṃsa describes the fall of a short-lived monarch, who was unnamed, but described as “impious and cruel”; whose palace was stormed by “those in ochre robes... led not by fury but by righteousness.” The implication is unmistakable: monks, perhaps under the direction of a senior abbot, staged a palace coup. Whether the king was killed or exiled is left ambiguous. The chronicler moves swiftly to praise the new ruler, one more “in tune with the law.” Modern historians, Gunasena (1974) among them, have speculated this may refer to the deposition of Mahinda V, or an abortive usurper during Kassapa’s reign. But the omission is as telling as the act. Regicide committed by monks could not be recorded plainly. It had to be ritually exercised and written every so vaguely that the very premise of it could be buried beneath euphemism. Still, the memory lingers.

07.The Sangha’s Double Legacy

To think of monks only as meditative renunciants is to ignore the full range of their historical presence. They were librarians and landlords, ritualists and revolutionaries, confessors and conspirators. And the kings who ruled with or against them knew this well. A throne without the sangha was no throne at all. But a sangha without the king could be just as dangerous.