01

|

|

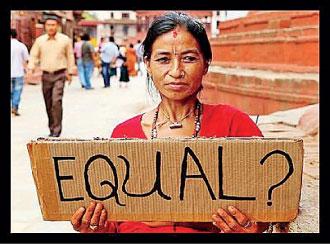

Gender inequality remains a daily reality for millions of women and girls. They suffer brutal practices ranging from female genital mutilation (FGM) and forced child marriage to sexual violence and discrimination at every turn. Globally, over 230 million women and girls have undergone FGM; a crime largely concentrated in Africa (144 million cases) but also affecting parts of Asia (80 million) and the Middle East (6 million). In one harrowing estimate, UNICEF reports that 370 million women and girls (1 in 8) were raped or sexually assaulted before age 18, with the numbers highest in Africa (79 million), East/Southeast Asia (75M), and South Asia (73M). Much of this violence is hidden: WHO finds that nearly 1 in 3 women worldwide experience physical or sexual violence in their lifetime. Alarmingly, most abusers are known to their victims; for example, in India 94.6% of rape offenders were acquaintances or family members. Deep cultural taboos and victim-blaming make “incest” and domestic rape almost invisible, as survivors are often shamed or silenced. In many societies “rape culture” pervades survivors face doubt and blame while perpetrators escape justice. Equality Now notes that in South Asia, a culture of shame shifts blames onto survivors, compounding barriers to justice.

02

East Asia and the Pacific

Even in rapidly modernizing East Asia, patriarchal norms constrain women’s lives. Education has improved, young women now often match or exceed men in school attendance, yet workplace inequality endures. In South Korea, only about 62% of women are employed (among ages 16–64), the lowest female rate in the OECD, and the gender wage gap is the largest in OECD countries. In Japan roughly 56% of women work (vs 72% of men), illustrating a large persistent gap. When women have children, many leave the labour force: OECD data show a characteristic “M-shaped” employment curve where Korean women’s labour force participation plunges in their 30s (childbearing age) then rises again. Discriminatory hiring and lack of affordable childcare further lock women out of careers. By one estimate, if East Asian women’s workforce participation matched men’s, regional GDP could rise by 3–5%.

Sexual violence is pervasive but underreported. UNICEF estimates that Eastern and South-Eastern Asia account for about 75 million female survivors of childhood rape or assault. Women and girls in the region also make up nearly 80% of trafficking victims, mostly into forced labour or sexual exploitation. For example, Myanmar and Cambodia face sex trafficking fuelled by poverty and demand. Reporting is rare: only 13% of Maldivian rape cases reach police, even though the crime is “common”. In rural China, marital rape is not explicitly outlawed, and authorities often blame victims. In Okinawa (Japan) and South Korea, women’s protests against military rape camps have met intense pushback.

FGM is not widely practiced in most East Asian societies, but pockets exist. UNICEF notes that Indonesia, the world’s largest Muslim country, has regions where FGM is common, especially on young girls. In China and South Korea, evidence of sex-selective abortion and female infanticide persists: China’s skewed sex ratio (117 boys per 100 girls) reveals that deep-seated son preference still leads many to abort or abandon baby girls. India similarly saw a long legacy of “missing girls” (the only large country where more baby girls die than boys), driven by sex-selective abortions and neglect. Despite these abuses, East Asia has strong women’s movements. In India and China, #MeToo campaigns (2018–2020) brought thousands of survivors forward. Japanese mothers’ unions successfully lobbied for better childcare laws, and Taiwanese and South Korean activists are pushing legal reforms on marital rape and pay transparency.

In Thailand and the Philippines, women protest annual “slut walks” and campaign against trafficking. These activists demand not only laws but a change in social attitudes, echoing the region’s own Confucian and Buddhist traditions of respecting women as mothers and leaders.

03

South Asia

In South Asia, patriarchal traditions remain shockingly strong. UNICEF reports that over 1 in 4 young women in the region were married before age 18, and the region is home to 45% of the world’s child brides (about 290 million). Deep poverty and conservative beliefs fuel forced child marriages: many families view girls as “burdens” or claim marriage “protects” them. In Bangladesh, nearly 47% of married teens (15–19) have already endured physical or sexual violence from their husbands. In Nepal and India, brides as young as 11 or 12 suffer early pregnancy and often severe obstetric injuries. The health impact is grave: UNICEF notes 3 out of 4 child brides in South Asia give birth during adolescence, risking both mother and infant lives.

Sexual violence is rampant, and victims are blamed. India’s National Crime Records Bureau reported that 10 Dalit (lower caste) women and girls are raped every day. Marital rape is still not criminalized in India, and police often dismiss family assaults as “domestic issues.” In Nepal, protests have erupted repeatedly (especially since 2018) as women demand accountability for gang rapes and public sexual assaults. Across rural South Asia, surveys show that many community leaders and police officers believe women “deserve” some beatings, worsening the culture of silence.

Poverty and limited schooling also trap girls. In rural Pakistan and Bangladesh, boys are preferred for scarce school seats; UNESCO estimates thousands of villages where girls’ schools are far away or non-existent. UNICEF warns that 46.5% of young women in South Asia are not in school, work or training, double the rate for young men. Those who do study often drop out at puberty, returning home to chores or marriages. As a result, female literacy in South Asia lags male literacy by over 10–15 percentage points in many areas.

The workforce reflects this gap. World Bank data show South Asia has one of the lowest female labour force participation rates in the world – only about 32% of working-age women are employed, versus 77% of men. Even in high-growth India, only a third of women work, many in insecure informal jobs. Women are also paid less: for example, in the USA (a global benchmark) women earned only 78 cents on the dollar compared to men in 2023, a gap that is often wider in South Asian economies. Rural women who do farm toil without land ownership or wages, while urban women struggle to break corporate glass ceilings.

One of the region’s darkest legacies is female infanticide and sex-selective abortion. In parts of India and among some diaspora communities, ultrasound technology has enabled parents to abort baby girls. UNICEF reports that India alone kills tens of thousands of unborn girls every year, and Bhutanese and Pakistani communities have similarly skewed birth ratios. These “missing girls” haunt families and society, reflecting extreme gender bias. Yet South Asia is also home to fierce activism. Stories like Sharmin Akter of Bangladesh, a 15-year-old who fought her forced marriage and won, inspire millions. Marches on International Women’s Day in Pakistan (#AuratMarch) and women’s rights rallies in India have grown each year. Girls’ education champions like Malala Yousafzai and Kailash Satyarthi highlight the cost of limiting girls. Legal reforms are happening too: India recently raised the legal marriage age and tightened rape laws (though enforcement remains spotty). Social media and NGOs pressure governments: for example, Bangladesh has banned dowry and child marriage multiple times, and grassroots programs train police on gender sensitivity.

04

Middle East and North Africa

Gender inequality in the Middle East is framed by a mix of modernity and tradition. Many MENA countries have doubled girls’ school enrolment in the past decades, yet women still face severe constraints. UNICEF notes that girls in the region are more than twice as likely as boys to be out of school or work. In several Gulf states, female literacy exceeds 90%, but labour force participation remains low (often 20–30%), due to conservative norms and legal restrictions. Across MENA, adolescent girls bear a “double burden” restricted by age and gender, with limited mobility and decision-making power.

Violence against women is pervasive but often hidden. WHO data show that in the Eastern Mediterranean region around 31% of women report intimate partner violence. Many Middle Eastern societies maintain strict codes of honour; rape victims can face social ostracism or even murder (honour killings), and reporting rates are low. Legal systems in some countries further entrench impunity: as Equality Now reports, marital rape is still not fully illegal in parts of the Middle East, and victims must meet draconian evidentiary standards. Afghanistan (though often counted in South Asia) still enforces child marriage and public lashings in some areas. Female genital mutilation is practiced in pockets of the Middle East too, notably in Egypt and Yemen (estimated 60–80% prevalence in parts of Egypt) and by some migrant communities.

Economic inequalities are stark. The World Bank notes that women in MENA account for only about 20% of the labour force, one of the lowest rates globally, despite rising numbers of university graduates. Pay and promotion gaps abound, especially in conservative oil-rich states where social norms discourage women’s outside employment. The region also has high rates of “NEET” (young women Not in Education, Employment, or Training), which hurts development.

Nonetheless, winds of change blow in the Middle East. Some countries have appointed women to parliament and ministries, and slowly lifted restrictions: Saudi Arabia now allows women to drive and open businesses without a male guardian. Women in Iran, Lebanon, and elsewhere bravely protest compulsory hijab laws and workplace harassment, often at great personal risk. The global #MeToo movement reached Egypt and Iraq, encouraging women to share stories. Gulf countries have begun to implement quotas and training programs for female employment. On the legal front, the African Women’s Committee (which includes North African countries) adopted a “Common Position to End Child Marriage” and many MENA states have outlawed female genital mutilation.

05

Sub-Saharan Africa

In Africa, the abuses are most extreme and widespread. Female genital mutilation is near-universal in some countries: Somalia, Guinea and Djibouti have over 90% prevalence among women. UNICEF’s data tell a grim story: of the 230 million FGM survivors worldwide, 144 million live in Africa. The practice is often defended in the name of tradition or “purity,” but it devastates health and violates human rights.

Prominent activists like Efua Dorkenoo (Ghana) and Aïssa Doumara (Chad) have campaigned to end FGM, and some governments (Kenya, Ghana, Burkina Faso) have passed strict bans. Yet progress is uneven: even where illegal, enforcement is weak, and tribal elders may oppose change. Encouragingly, UNICEF found that two-thirds of people in practicing communities want FGM to end, showing cultural norms can shift.

Child marriage and forced unions are also prevalent. In West and Central Africa about 41% of girls marry before 18; six of the ten highest child-marriage countries are in this region. In Eastern and Southern Africa, nearly one-third of women were married as children, accounting for 50 million child brides. These brides drop out of school en masse, suffer domestic abuse, and face deadly obstetric risks. Girls in conflict zones are especially vulnerable: in places like Somalia and South Sudan, famine or war can lead desperate families to marry off daughters for dowries or “protection.” African Union initiatives (e.g. the “Campaign to End Child Marriage”) and NGOs like UNICEF and Plan International are mobilizing communities and passing laws to raise the marriage age, with some success. Still, traditional leaders’ resistance and lack of birth registration allow child marriages to continue underground.

Gender-based violence in Africa is alarmingly high. WHO estimates roughly 33% of women in Sub-Saharan Africa endure partner violence. Conflict zones bring hellish atrocities: human-rights groups report mass rapes in wars (Congo, Nigeria, Sudan) used as weapons of terror. In peacetime too, courts in parts of Africa often treat rape as a minor offense; victims rarely press charges due to stigma or distrust of police. Domestic violence goes largely unchecked: surveys in South Africa, Kenya, and Nigeria show about a third of women have been beaten by a partner. Victim-blaming is endemic, and authorities frequently dismiss violence as a “private family matter.” UNICEF and African activists stress that legal reforms (covering rape, marital rape, child abuse) and women’s shelters are urgent needs.

On opportunity, African women still lag men. Fewer girls finish secondary school in many countries due to distance, poverty and cultural bias. Even where girls attend school (as in Rwanda or Botswana), they often study softer subjects and face discrimination in higher education. In the workforce, African women do much of the subsistence farming but have far less land ownership or credit access. In formal sectors, women are underrepresented in leadership and STEM fields. According to UN figures, women and girls account for over 70% of trafficking victims in Africa, mainly for forced labour and sexual exploitation. Trafficking networks prey on poverty: girls from rural villages or war-torn regions are lured to cities or abroad by false job promises. International organizations (UNODC, IOM) emphasize that combating trafficking in Africa requires tackling root causes, poverty, conflict and gender inequity, not just law enforcement.

Despite these grim realities, African women are unbowed. Grassroots movements are growing. In Liberia and Tunisia, survivors of rape camps and honour killings have publicly protested for justice. South Africa’s U.S. (Stand Up Speak Up) campaign raises awareness about rape and domestic abuse. In education, campaigns like Malala Fund and Camfed recruit local “education mentors” to keep girls in school. Governments have begun to respond: many African nations now criminalize FGM, and organizations like UN Women work with chiefs to abandon harmful traditions. The African Union’s “Maputo Protocol” and continental action plans (e.g. against femicide) symbolize a regional solidarity. At the community level, initiatives like Tostan’s empowerment programs in Senegal show that even in remote villages, social norms can be transformed when women and men talk openly about human rights.

06

Global Solidarity for Change

The suffering is stark, but the root causes are alarmingly similar across continents: entrenched patriarchy, poverty, illiteracy and rigid traditions that treat girls as inferior. In every region, gender-based violence and discrimination persist not because of biology but because of power. Yet history shows change is possible. In many African and Asian countries, girls’ enrolment has soared in the past 20 years, a testament to families and advocates who fought for education. Global movements have chipped away at the taboos: international campaigns, from UN resolutions to #MeToo hashtags, have helped survivors speak out and find allies.

In each region, ordinary women and courageous activists have made progress. UNICEF and WHO data highlight problems, but on the ground teachers, social workers, police trainers and NGOs are tirelessly working to protect rights. Laws to ban FGM or marital rape or child marriage are being adopted or strengthened across Asia, Africa and the Middle East, even if enforcement remains uneven. More women than ever are running for office, unionizing, and building businesses. Young men, too, are joining the fight, realizing that gender equality lifts entire communities.

The message is clear: Gender equality is not just a women’s issue; it’s a human issue. When girls are educated, economies grow; when women are safe at home, societies heal. An injury to one is an injury to all. As the UN emphasizes, ending practices like FGM or child marriage is not simply about changing a law but transforming minds. Global solidarity, across cultures and borders, is essential. Every citizen, whether in Sri Lanka or Senegal, has a role in speaking out against injustice, supporting victims and demanding accountability.

The journey to equality is long and hard, but it is driven by hope and compassion. We remember voices like Sharmin Akter’s, who refused a forced marriage and now champions girls’ rights. We stand with women like Malala, Tawakkol Karman and thousands of unnamed activists who remind us that a better world is possible. For the sake of our daughters and all future generations, we must commit to shattering the silence. Only together can the global community end these injustices and secure a future where every girl and woman can live without fear, discrimination or violence; with equal dignity, opportunity and hope.

This article was written by a team of Gen Z contributors at ‘The Sun’ (Daily Mirror).