In the complex tapestry of Sri Lankan cultural life, the Nachchi community stands as a resilient symbol of gender diversity, tradition, and self-fashioned kinship. Far beyond the glimmer of dance stages or ceremonial performances, the Nachchi identity weaves together rich cultural customs, spiritual devotion, and a deeply rooted form of communal care. Their history and lived experience highlight Sri Lanka’s capacity for pluralism in gender identity, even as the community has endured marginalization and misunderstanding.

Origins and the Meaning of “Nachchi”

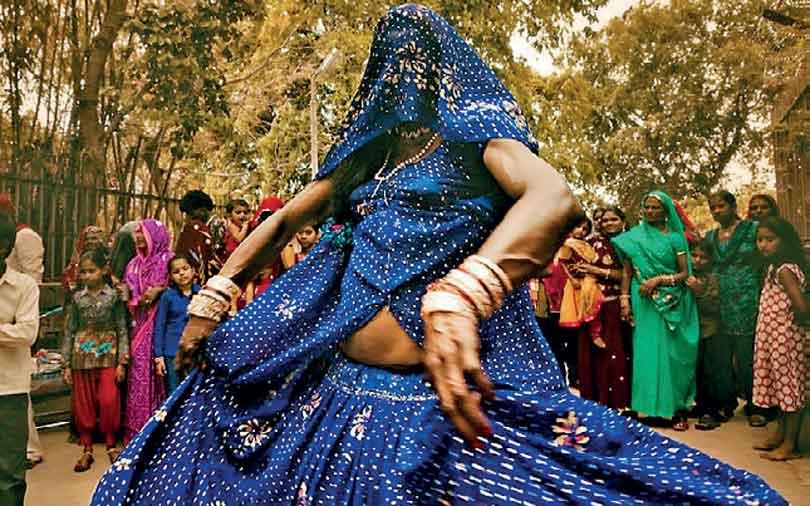

The term Nachchi is believed to be derived from the Hindi word nautan, meaning ‘dancer.’ The community itself dates back to the late 19th century, when Nachchis - typically transgender women, were introduced into Sri Lankan social life as entertainers. They became notable presences at festive and ceremonial events in areas such as Bilinwatta and Kotahena, eventually expanding into Moratuwa, Dehiwala, and Negombo. In those early years, the Nachchis were respected cultural contributors. They performed at ceremonies; weddings, funerals, and New Year gatherings, not only as dancers and singers but also in various roles including cooking, makeup artistry, and household thrift. Their presence was seen as auspicious and added a particular vibrancy and elegance to community life.

The Nachchi Mother and Community Kinship

One of the most remarkable elements of the Nachchi community is its unique family structure, centered on the role of the Nachchi Mother. Typically, an older transgender woman, the Nachchi Mother serves as a mentor, caretaker, and spiritual guide to younger Nachchis. This familial model is built on mutual aid, emotional support, and collective survival. It challenges mainstream conceptions of family and gender roles, replacing biological ties with chosen kinship. Within this structure, younger Nachchis, often rejected by their biological families, find acceptance, guidance, and protection. The Nachchi Mother provides housing, teaches performance skills, and imparts wisdom about navigating a society that often marginalizes them. This form of caregiving is more than just practical; it is profoundly symbolic of a long-standing tradition of self-sustaining community building.

Sacred Rituals and Spiritual Dimensions

The spiritual life of the Nachchi community is another vital, yet often overlooked, dimension of their identity. Many Nachchis engage in devotional practices to deities such as Goddess Pattini and Goddess Kali, invoking feminine divine energy as a reflection and validation of their gender identities.

One especially sacred ritual is the Dehi Mangalyaya, a ceremonial rite of passage that welcomes individuals into the Nachchi community. Much like initiation ceremonies in other cultures, the Dehi Mangalyaya marks the formal and spiritual beginning of a Nachchi’s journey. These rituals are deeply significant - not only for their religious meaning but also for how they challenge conventional gender norms and offer alternative spiritual frameworks for gender expression. In one documented case, a revered individual known as Karu Mama was known to ‘perform’ as Goddess Pattini, taking on the mantle of the deity in elaborate rituals that blurred the lines between performance, devotion, and identity. These events are more than spectacles; they are acts of cultural reclamation and spiritual affirmation.

Stigma, Discrimination, and the Changing Use of Language

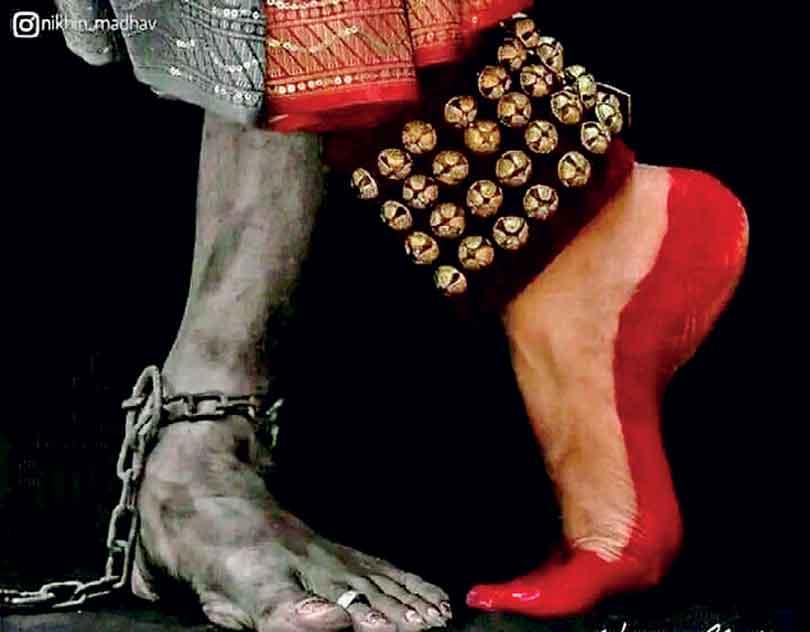

Despite their deep cultural roots and spiritual importance, the Nachchi community has endured longstanding social challenges. Over time, the term Nachchi, once a source of pride, became stigmatized, often unfairly associated with sex work. This association, compounded by social ostracism, has led to significant marginalization, including harassment and abuse from law enforcement agencies. In modern Sri Lanka, the consequences of this stigmatization are profound. Many Nachchis face employment discrimination, housing insecurity, and violence, both verbal and physical. As a result, a growing number of community members prefer the term ‘trans woman’ to describe themselves. The shift in language reflects a desire for social respectability and recognition, especially in professional and public life. It is also a strategic choice, aimed at navigating a world that continues to police gender boundaries. While some might interpret this linguistic transition as a departure from tradition, others see it as an evolution; a way of asserting identity in a more inclusive, global language while still maintaining cultural specificity.

Cultural Contributions Beyond Performance

The idea that the Nachchis are merely performers does a disservice to the rich contributions they have made to Sri Lankan society. Their roles in traditional ceremonies, their participation in spiritual rituals, and their work in areas such as beauty, fashion, and domestic organization point to a holistic cultural presence. It is important to recognize that their performances were never just about entertainment. They were forms of storytelling, gender expression, and cultural transmission. In many ways, the Nachchis were early gender theorists, living embodiments of fluidity and multiplicity long before such ideas entered academic or activist discourse. Moreover, their existence raises broader questions about gender identity within South Asian cultural frameworks. Unlike the often-rigid binary system in the West, the existence of communities like the Nachchis (and similar identities such as the Hijra in India or Aravani in Tamil Nadu) suggests that Sri Lanka, and South Asia more broadly, has always had space for gender plurality, even if that space has been contested or obscured by colonial influence and modern conservatism.

Toward Recognition and Respect

Today, as Sri Lanka grapples with questions of gender rights and social justice, the story of the Nachchi community remains deeply relevant. Their resilience is inspiring, but it also underscores the urgent need for systemic change, legal protection, social services, healthcare access, and representation in public discourse. Organizations and activists have begun the work of documenting Nachchi histories, advocating for their inclusion in broader LGBTQ+ rights movements, and challenging the stereotypes that have haunted them for decades. Yet much more remains to be done. Recognition must move beyond token performances at cultural festivals or inclusion in documentaries; it must extend to policy reform, education, and social integration.

Conclusion

The Nachchi identity is not a relic of the past or a side note in cultural history. It is a living, breathing tradition, a complex interplay of art, gender, kinship, and faith. Their story is one of survival, adaptation, and resistance in the face of systemic marginalization. Beyond the stage, the Nachchis carry with them a profound legacy that challenges us to think differently about gender, culture, and community. In honoring their contributions, we do more than pay tribute to a marginalized group, we open up the possibility for a more inclusive, empathetic, and plural Sri Lanka.