India was meant to outgrow caste. When the Constitution came into force in 1950, it outlawed untouchability under Article 17 and promised that no person would be judged by birth. It was the promise of rebirth; a nation cleansing itself of an ancient cruelty. Yet as 2025 unfolds, the promise feels unfinished. Caste, far from disappearing, has learned to disguise itself. It now hides behind class and privilege, behind accents and surnames, behind who gets to enter certain schools or who gets a fair chance at a government job.

It decides who marries whom, whose voice counts in a crowd, and, tragically, who lives and who dies. From the rice fields of Tamil Nadu to university corridors in Bengaluru, from Dalit colonies in Uttar Pradesh to film studios in Mumbai, caste remains India’s most enduring social wound.

The story of caste is not ancient mythology; it is modern architecture. The Hindu varna system once divided society into four broad groups: Brahmins, the priests and scholars; Kshatriyas, the warriors and rulers; Vaishyas, the merchants and traders; and Shudras, the service providers and labourers. Outside these varnas were the avarna, literally, those “without varna,” people now known as Dalits, formerly called “untouchables.” They performed tasks considered impure, such as cleaning, leatherwork, and handling the dead. Over centuries, these categories hardened into hereditary jatis, or subcastes, tied to specific occupations and closed marriages. What began as a division of labour ossified into a division of dignity.

Colonial rule reinforced the structure further. British census administrators classified Indians by caste and gave bureaucratic recognition to jati names, converting fluid social identities into fixed legal categories. By the time India won independence, caste was not merely a social reality but a bureaucratic one. Today, the state officially recognises three groups for affirmative action: Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST), and Other Backward Classes (OBC). Together they form more than half of India’s population. Reservations in education, government employment, and politics were designed to redress historic exclusion. But enforcement is uneven, and prejudice runs deeper than paperwork.

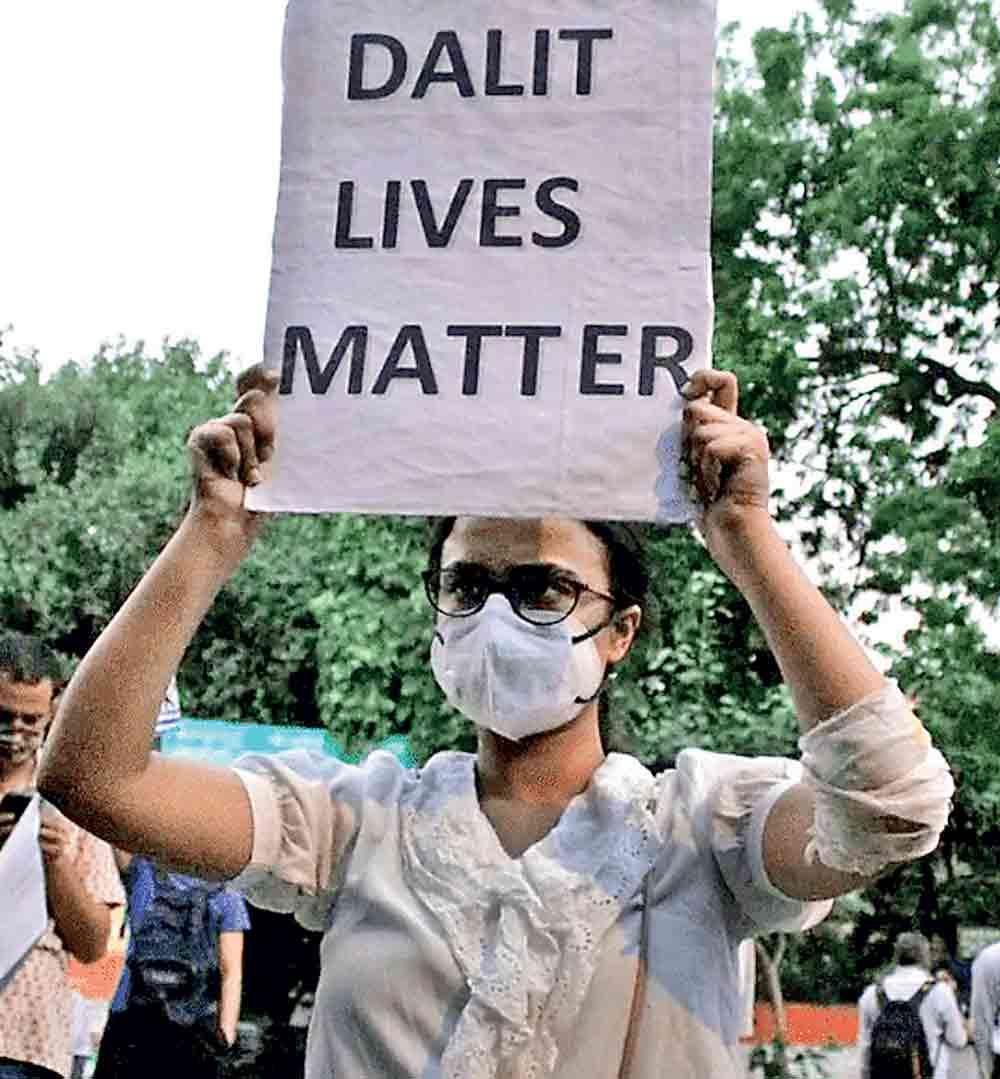

In Karnataka in 2024, a decade-old case reached verdict. The Marakumbi attacks of 2014, in which a Dalit settlement was torched and dozens beaten, ended with life sentences for many perpetrators. Yet soon after, appeals and bail petitions began. Survivors who had waited ten years for justice found themselves reliving the trauma in new hearings. The courts may convict, but the social order rarely changes. In May 2025, in Perungudi near Madurai, nineteen-year-old C. Alagar, known as Ajay, was beaten by nine men who hurled caste slurs. He died of his injuries days later. The police booked the assailants under the SC/ST Prevention of Atrocities Act. His mother refused to cremate his body until arrests were made. A few weeks later, in Alwar, Rajasthan, three police constables were charged with raping a minor Dalit girl. The outrage was not only over the crime but over who the accused were, men sworn to protect citizens. In October, in Ambedkarnagar, Uttar Pradesh, a Class-12 Dalit student was found strangled in a sugarcane field. Her bicycle and shoes were found nearby. The investigation crawled. Locals protested. For many, it was a chilling reminder that Dalit girls remain among India’s most vulnerable citizens. Each story is specific, yet together they form a pattern. Caste is not an idea of the past; it is a living code of power.

The emotional map of caste India is drawn in fear and resilience. Fear, because violence is arbitrary, it can erupt over a marriage, a water source, a pair of sandals. Grief, because the victims are often young: students, labourers, children. Betrayal, because institutions meant to protect, the police, the judiciary, the schools, often fail to respond with urgency. And resilience, because the oppressed refuse to disappear.

S. P. Balasubramaniam

Across the country, new Dalit and OBC voices are emerging in film, music, politics, and sport, voices that speak not from pity but from power. Their journeys, scattered across decades and industries, form a parallel history of Indian popular culture. In the 1970s, Rajesh Khanna became India’s first superstar, a man whose smile defined an era of cinema. Few knew that Khanna hailed from a Kayastha family in Punjab, an Other Backward Class background. His superstardom, achieved in an industry then dominated by upper-caste heroes, quietly expanded the idea of who could represent the Indian dream. In the South, the legend of Rajinikanth still towers above all else. Born into a poor Maratha (OBC) family in Karnataka, he worked as a bus conductor before becoming the most beloved figure in Tamil cinema. His life, mythologised on screen and off, represents the ultimate story of upward mobility; a man from the margins turned cultural god. His films, filled with swagger and morality, became lessons in self-respect for audiences who saw themselves reflected in his journey.

Rajinikanth

The same current runs through the life of S. P. Balasubramaniam, the legendary playback singer who recorded more than 40,000 songs in sixteen languages. Coming from a Balija (OBC) family in South India, his honeyed voice defined the emotional tone of an entire generation. SPB’s success was proof that art could transcend social divisions even when society could not. In Tamil cinema today, that spirit continues with filmmakers like Nagraj Manjule and Pa. Ranjith. Manjule’s films, Fandry and Sairat, forced Indian audiences to confront caste head-on. Sairat, a love story between a Dalit boy and an upper-caste girl, became a cultural phenomenon not just for its artistry but for its defiance. Manjule, grew up in a Dalit family in Maharashtra. In neighbouring Tamil Nadu, Pa. Ranjith has built an entire cinematic movement around Dalit pride. His films Kabali and Kaala, both starring superstar Rajinikanth, turned the traditional hero myth on its head. The hero was no longer the saviour from above but the rebel from below. Through his Neelam Cultural Centre, Ranjith nurtures Dalit artists, writers, and musicians, transforming cinema into a tool for social assertion. Even actors who rarely speak about caste directly become symbols of its quiet defiance. Dhanush, one of Tamil cinema’s most successful stars and a two-time National Award winner, was born into the Pallar community, a Scheduled Caste group. Despite early typecasting and prejudice, his rise in an industry that prizes fair skin and upper-caste lineage is extraordinary. His 2019 film Asuran, based on a real Dalit uprising, felt like an echo of his own family’s past.

Dhanush

The Bollywood world, which prefers its heroes polished and caste-neutral, has seen fewer explicit confrontations with identity. Yet cracks have appeared. Manoj Bajpayee, an actor from Bihar’s Yadav (OBC) community, has spoken about the class and cultural bias he faced when he moved to Delhi’s theatre scene. His success today, built on roles that celebrate grit, intelligence, and moral complexity, challenges the long monopoly of upper-caste narratives in Hindi cinema. The story of representation is similar in music and sport. S. P. Balasubramaniam’s journey from an OBC village boy to the voice of India’s romantic imagination mirrors, in many ways, the journey of Mahendra Singh Dhoni from a railway ticket collector to the captain who lifted the Cricket World Cup. Dhoni belongs to the Kurmi community, classified as OBC in Jharkhand, and his rise is a social revolution disguised as a sports story; proof that talent can occasionally outrun the old hierarchies.

Umesh Yadav, the fast bowler from Nagpur, was born into an Adivasi (tribal) family; his father worked in coal mines. When Umesh first represented India, his parents could not afford a television to watch him. Today, boys in small tribal towns cite his name as a beacon. And then there is Vinod Kambli, once hailed as a prodigy, the boy who outshone Sachin Tendulkar in school cricket. Kambli, a Dalit, became the first lower-caste player to score a double century in Test cricket. Yet his career, unlike Tendulkar’s, faltered early. He later spoke of feeling isolated and discriminated against. Kambli’s story remains a haunting example of how invisible walls can still shape visible talent. These cultural figures, actors, directors, singers, cricketers, represent a generation unafraid to exist in defiance of caste. They prove that art, sport, and ambition can be acts of resistance. Yet their success does not erase the violence on the ground. Representation matters, but it coexists with the daily humiliations faced by millions.

Manoj Bajpayee

For every Rajinikanth who conquers the screen, there is a young man like Ajay in Madurai who dies for daring to walk freely in a public space. Universities were once imagined as the sanctuaries of equality. Reservation policies, quotas for SC, ST, and OBC students, were meant to open doors previously closed. They worked; first-generation students entered IITs, IIMs, and central universities. Yet many describe campuses as hostile environments. Dalit and OBC students speak of isolation, coded insults, and professors who grade them unfairly. In 2025, the Supreme Court directed universities to strengthen anti-discrimination and anti-ragging frameworks, requiring internal committees to include student representatives from marginalized groups. But rules cannot erase bias embedded in daily interactions. The tragic suicides of Dalit students, including Rohith Vemula in 2016 and several others since, continue to haunt Indian higher education. Their death notes often echo a similar despair: of being invisible in spaces that celebrate merit but ignore privilege.

Some find escape through faith. Conversion, for Dalits and OBCs, is not only a spiritual act but a declaration of dignity. The most famous example came in 1956, when Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the architect of India’s Constitution and a Dalit himself, led half a million followers to convert to Buddhism. He saw it as liberation from the script of hierarchy. His words, “I was born a Hindu, but I will not die a Hindu,” still resonate. Today, conversions to Buddhism continue, often following incidents of violence or humiliation. Mass ceremonies in Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh see thousands taking vows of equality. Others choose Christianity or Islam, sometimes for community, sometimes for survival. But even there, the ghost of caste follows. Dalit Christians and Dalit Muslims often face social exclusion within their own congregations. In many states, laws restricting religious conversion have made such moves fraught with danger.

M. S. Dhoni

Why does caste persist? The answer lies not in religion alone but in structure. Caste endures because it is built into every layer of life, the language of everyday interaction, patterns of marriage, ownership of land, control of education, and access to capital. It survives through cultural internalisation, economic dependency, institutional bias, and political manipulation.

- Economic disparity sustains it; upper-caste families continue to dominate land ownership and high-income professions.

- Institutional bias sustains it; police officers, teachers, and bureaucrats often reproduce caste hierarchies in their behaviour.

- Political opportunism sustains it: caste blocs remain reliable voting units, mobilised at election time and forgotten afterward.

- And gender intensifies it: Dalit women face violence both for their caste and their gender, making them some of India’s most vulnerable citizens.

The National Crime Records Bureau reported over 50,000 cases of caste-based crimes in 2024, a number widely considered underreported. For every registered case, activists say dozens go unrecorded, either out of fear or fatigue. The SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, amended in 2018 to strengthen protection, has been used effectively in some states but diluted by slow courts and weak enforcement in others. Yet amid the pain, there are triumphs of endurance. In Tamil Nadu, the young Dalit writer Imayam’s novels sell thousands of copies, chronicling the lives of rural labourers with unsparing truth. In Maharashtra, Dalit rappers like Sumeet Samos and The Casteless Collective, use hip-hop as a weapon, turning the humiliation of caste into poetry of protest. In Delhi, Dalit and OBC student groups run reading circles on Ambedkar, Phule, and Periyar, reclaiming intellectual space once denied to them. Each crime and each success tell a story about belonging. The mother in Madurai who lost her son. The student in Hyderabad who is the first in her family to enter a university. The cricketer who rose from a mining town to the national team. The director who turned pain into cinema. Together, they draw a portrait of a country that has both changed and refused to change.

Vinod Kambli

There is progress to celebrate. Special courts under the SC/ST Act have delivered key convictions. Reservation policies have created an educated middle class among Dalits and OBCs - doctors, engineers, bureaucrats, journalists. Civil society campaigns and media coverage have pushed governments to respond faster. But legal victories alone do not dissolve centuries of prejudice. What must change next is not merely the law but the language of equality. Justice delayed is justice denied, yes - but dignity denied is humanity undone. India’s moral challenge is not just to punish atrocity but to unlearn hierarchy. Schools must teach empathy alongside arithmetic. Universities must celebrate diversity not as tokenism but as strength. Workplaces must see inclusion not as charity but as fairness. And the law must act with urgency, protecting those who have never been protected before. Conversions to Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam are often treated as rebellion. In truth, they are affirmations, of the right to live without being humiliated for one’s birth. They are reminders that faith, at its best, is a language of equality.

As India approaches eighty years of independence, the question remains painfully simple; can the country imagine itself beyond caste? The answer, perhaps, lies not in statistics but in stories, in every person who refuses to accept their assigned place. In 2025, the caste system no longer dictates who can enter a school or cast a vote, at least not officially. But it still dictates who feels safe walking home at night, who is heard in a meeting, and who is trusted to lead. Dismantling it will take more than laws or slogans. It will take courage: from those with privilege to acknowledge it, and from those without to keep demanding dignity.

The young cricketer running on a dusty pitch in Nagpur, the film director rewriting heroism in Chennai, the mother protesting outside a police station in Madurai, they are all part of the same story. It is the story of a country still learning to treat its own children as equals. Caste was not built in a day; it will not disappear in a decade. But every act of resistance, a film, a protest, a conversion, a poem, a dream, chips away at its walls. India’s progress will not be measured by GDP or global rankings, but by one quieter metric; the dignity with which its poorest, darkest, lowest-born citizens can walk, speak, love, and live. Until then, the caste that refuses to die will remain both India’s greatest shame and its most urgent unfinished battle.

Sagar Shejwal: Found in a Field

In 2015, 24-year-old Sagar Shejwal, a nursing student, travelled to Shirdi, Maharashtra, to attend a wedding. While walking by a liquor shop with friends, his phone rang with a ringtone honouring Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, a Dalit icon. According to the complaint, upper-caste men drinking nearby demanded he change the ringtone. When he refused, they assaulted him. He was later found dead in a nearby field with multiple fractures. An autopsy revealed grievous injuries, including evidence that a vehicle may have driven over him. The fact that his assailants were granted bail shows how caste-based violence often meets the blunt machinery of law with indifference. His death became a rallying point in protests over potential weakening of the SC/ST Act.

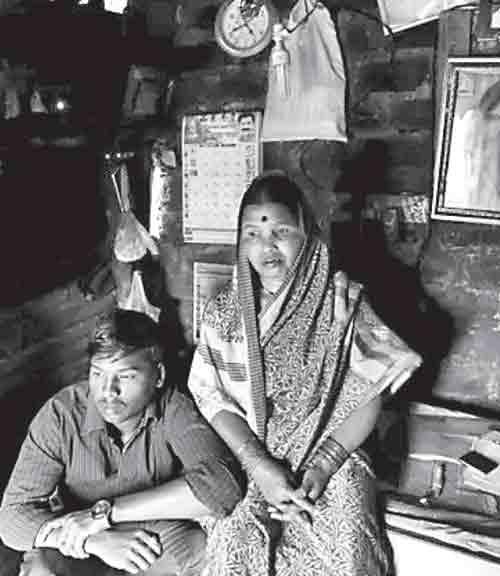

Manik Udage: Found in a Quarry

Manik Udage’s brother, Shravan, and his mother

Manik Udage, aged 25, was reportedly murdered in 2014 because he arranged a large public event honouring Dr. B.R. Ambedkar. His intention offended upper-caste neighbours who allegedly asked him to shift the venue. When he refused, he was kidnapped, beaten with a steel rod, and his body was found in a quarry days later. The investigation led to the arrest of four upper-caste suspects, who were denied bail repeatedly. But the family says fear persists, they avoid traveling through certain neighbourhoods out of safety concerns. The episode highlights how Dalit assertion of identity (commemorating Dr. B.R. Ambedkar) attracts violent backlash in zones of social control.

Sanjay Danane: “Staged to Look Like Suicide”

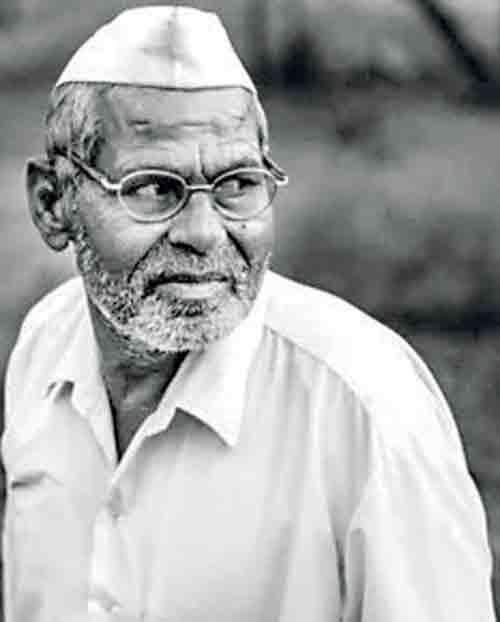

Sanjay Danane's Father

In 2010, Sanjay Danane, 38, was found hanged near the school where he taught. His parents allege he was murdered by upper-caste school colleagues over long-standing disputes, and the hanging was orchestrated to appear self-inflicted. Authorities arrested around 18 people, including teachers, board members, and the principal, though all eventually obtained bail. The case reflects how workplace caste conflict blends with institutional power to mask violence, especially when the accused include authority figures.

Rajashree Kamble: Deprived of Water

Rajashree's father, Namdev Kamble

Ten-year-old Rajashree Kamble died after slipping and injuring her head while fetching water. Her father says that the Dalit colony where they lived had been denied water supply by the village council, even though neighbouring upper-caste localities continued to receive it. The wells had dried up, and the village leadership allegedly prioritized other areas. Attempts to lodge police complaints failed repeatedly.

This is a quieter, structural form of violence; deprivation of basic public utilities as a method of exclusion and neglect, sometimes with fatal consequences.

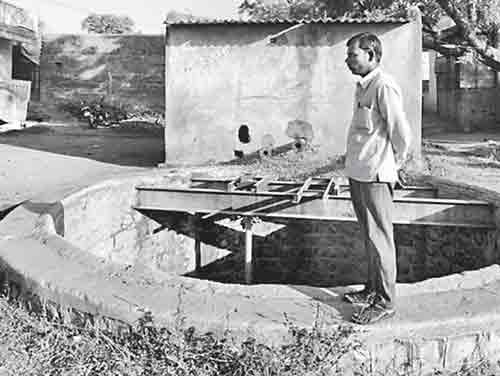

Madhukar Ghadge: Stabbed for Digging a Well

Madhukar Ghadge's son Tushar

Madhukar Ghadge, aged 48, attempted to dig a well on his own land (which lay adjacent to land owned by upper-caste families). He was attacked by twelve men with spear-like weapons. He died of wounds at hospital. A lower court later acquitted all 12 accused for lack of evidence, but an appeal continues in the Mumbai High Court. The case reveals how Dalits’ attempt to claim land or resources, even within legal rights, is often met with violent pushback.

Nitin Aage: Hanging from a Tree

In April 2014, 17-year-old Nitin Aage from Kharda village was found hanging from a tree. He had reportedly been speaking with a girl from an upper-caste community and faced harassment from her family. The police believe he was first beaten, then strangled, and later hung from the tree to stage a suicide. Thirteen men were accused, but in 2017, all were acquitted. The family has pressed for a retrial. This case demonstrates how violence is camouflaged as self-harm or suicide to obscure caste motives, and how the acquittal of accused emboldens impunity.

Rohan Kakade: Beheaded and Burnt

Rohan's Mother

On 30 April 2009, the day before his 19th birthday, Rohan Kakade disappeared. His body was discovered hours later; beheaded and set on fire. The accused, five men from upper-caste backgrounds, believed he had been in a romantic relationship with one of their sisters. His parents argued that no such relationship existed; it had been gossip. All five accused were eventually acquitted, and his mother continued to fight legal battles even after his father passed away. This is one of the more extreme cases of caste-based violence, combining sexual morality, honour, and brutality.

Prashant Solanki: Threatened for riding a horse to a wedding

In June 2018, a Dalit man in his late twenties named Prashant Solanki was on his way to his wedding, riding a decorated horse, a customary gesture of honour in many Indian weddings. Upper-caste villagers confronted him, saying that riding a horse was a “privilege” reserved for upper castes. The men threatened Solanki and his family, demanding that he abandon the horse or face violence. Solanki, fearing for his life, had police escort him to his bride’s home and wedding venue. This case is remarkable because it involves an act (riding a horse) that is culturally symbolic, a signifier of status, being monopolized by caste identity. What seems like a personal celebration became a flashpoint of communal policing.

Killed for sitting cross-legged (Tamil Nadu)

In southern Tamil Nadu, two Dalit men were killed by upper-caste villagers after one of them sat cross-legged during a temple ritual. According to the attackers, that posture was disrespectful, “dishonourable,” and outside the caste norms. About fifteen men reportedly ambushed the Dalits’ neighbourhood. At least six people were injured and houses damaged. The narrative of orthodoxy and purity is deeply woven into caste norms. Sitting cross-legged was declared an insult, and the response was lethal. The violence underscores how even spatial gestures, how one sits or where one presumes entitlement, are tightly monitored.

Stripped, beaten, paraded naked for swimming in a well (Maharashtra)

Three Dalit boys in Maharashtra were arrested, stripped naked, beaten, and paraded through the village by upper-caste villagers after they were caught swimming in a well owned by an upper-caste family. A video of the assault circulated widely, showing two of the boys attempting to cover themselves with leaves while being struck with sticks and belts. Laughter is audible in the background.

One mother, having seen the video online, told BBC Marathi, “We are afraid of further attacks.” The local police had arrested two men in connection with the assault, but the victims and their families remain fearful.

Beaten for wearing “royal” shoes (Gujarat)

A 13-year-old Dalit boy named Mahesh Rathod was attacked in Gujarat for wearing a pair of “mojris” (traditional leather shoes often associated with upper classes), along with jeans and a gold chain. A group of men approached him, asked his caste, and upon learning he was Dalit, claimed he was “posing” as upper caste by wearing such footwear and accessories. They beat him with sticks while he pleaded. The incident was captured on video. Afterward, the local media reported that Mahesh was placed under police protection. The violence was motivated not by a crime or theft but by what the attackers saw as a breach of caste symbolism. Wearing shoes “unequal” to one’s caste became a punishable offense in their eyes.

Violence over a Facebook name suffix (Gujarat)

In another case from Gujarat, a Dalit man named Maulik Jadav added the suffix “sinh” to his first name on Facebook (Mauliksinh). “Sinh” is a suffix traditionally used by some upper-caste groups in that region. Harassment followed; threats over phone and on Facebook, demanding he drop the suffix. When he refused, he was attacked at home. In retaliation, Dalit residents in his community stormed the house of an upper-caste man. The escalation from online identity to physical violence shows how caste norms influence even digital self-expression. A subtle act of naming was perceived as an assertion of higher status and met with aggression.